Fig. 71.1

Histology of PAP. Well-preserved alveoli with the accumulation of amorphous lipoproteinaceous material that stains pink with periodic acid-Schiff stain and a distinct absence of inflammatory cells

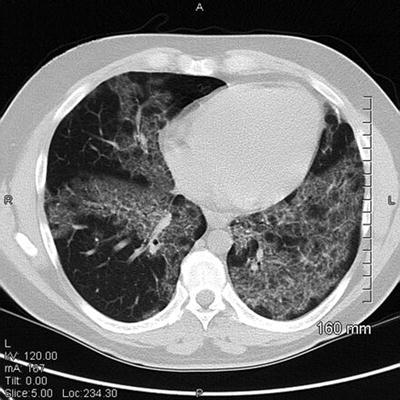

Fig. 71.2

CT scan image of PAP. Patchy areas of ground glass with thickening of the interlobular septa creating a “crazy-paving” pattern

2.

Inhalational lung toxicities

Case reports have suggested WLL as a therapeutic option in inhalational lung injuries, predominantly occupational lung disorders with diffuse pulmonary damage. In these situations, WLL is aimed at removing the mineral dust that cannot be otherwise eliminated by the body. Whole-lung lavage has been performed in patients with exogenous lipoid pneumonia, acute silicosis, lung injury from inhaled plutonium oxide, and pneumoconiosis. Long-term benefits of WLL in these situations are unknown.

Effects of WLL

Beneficial effects of WLL are well established in case series of patients with PAP. Although no criteria to measure adequacy of response are established, 84 % of the patients have a significant clinical, physiologic, and radiologic improvement following WLL. Patients who undergo WLL at any time during the course of their disease have a survival benefit when compared to those who do not undergo the procedure (Fig. 71.3). Studies that compare pulmonary parameters (PaO2, A-a gradient, DLco, vital capacity, pulmonary shunt fraction) before and after performing WLL have shown a significant improvement with the procedure. The median duration of benefit following WLL is 15 months, and approximately two-thirds of the patients will require a repeat lavage, usually within 6–12 months.

Fig. 71.3

Overall survival from the time of diagnosis of acquired PAP was significantly improved if patients had received therapeutic lavage at any time during their disease course (lavage, n = 146; no lavage, n = 85; p = 0.044) (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © American Thoracic Society. Seymour JF, Presneill JJ. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis progress in the first 44 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:215–35. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society)

Procedural Considerations

1.

Equipment

Lavage is performed with 15–20 L of sterile normal saline, and the fluid is run through a blood warmer to maintain adequate core body temperature. We also recommend a warming blanket (Bair Hugger; Arizant, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN) covering the exposed body surface to prevent hypothermia, given the prolonged duration of the procedure. Tubing that is generally used for intravenous fluids is connected via an adapter to the double-lumen endotracheal tube to form the inflow and the outflow limbs. Flow through the tubing is controlled with stopcocks. A thin bronchoscope that can be used through the double-lumen endotracheal tube to verify tube position or aspirate secretions should be available at patient’s side. Multiple drainage receptacles are needed to collect the effluent. Anesthesia team that is comfortable with intubation with a double-lumen endotracheal tube and single-lung ventilation is required for the procedure.

2.

Procedure

General anesthesia is recommended for the procedure. The patient is initially placed on their back on the operating table and intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube. Flexible bronchoscope is used to confirm the tube placement. The bronchial and the tracheal balloons are inflated to isolate the lungs, and double-lung mechanical ventilation is initiated. The patient is then turned to a lateral decubitus position, with the lung being lavaged up in the nondependent position. Meticulous care should be taken to avoid ischemic complications to the extremities by placing supporting pillows in the axilla, under the head, and between the thighs. The position of the endotracheal tube should be reconfirmed. Lung isolation is confirmed by immersing the end of each lumen of endotracheal tube in water and observing for air bubbles while ventilating the other lung. Single-lung ventilation is then initiated, and the tube to the lung to be lavaged is opened to the atmosphere and allowed to deflate. The limb of the double-lumen endotracheal tube that is open to the lung to be lavaged is then connected to the normal saline reservoir (Fig. 71.4). Prior to filling the lung with the fluid, sufficient time should be given to confirm adequate oxygenation while ventilating a single lung.