When to Test and What to Order

The recommendations for preoperative testing are listed in Chapter 10. Although there are many other situations in which pulmonary function testing is indicated, for reasons that are unclear these tests are underutilized. This chapter describes instances in which testing is warranted and includes the basic tests to be ordered. Depending on the initial test results, additional studies may be indicated.

13A. The Smoker

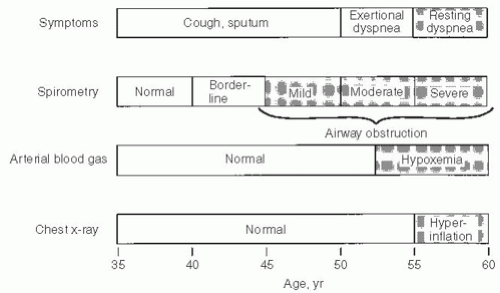

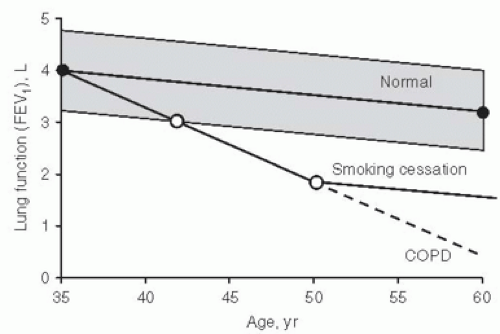

Even if smokers have minimal respiratory symptoms, they should be tested by age 40. Depending on the results and a patient’s smoking habits, repeat testing every 3 to 5 years is reasonable. The logic for early testing is shown in Figure 13-1. This shows the typical pattern of development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Spirometry is the first test to have abnormal results. The innocuous cigarette cough may indicate significant airway obstruction. When confronted with an abnormal test result, a patient can often be convinced to make a serious attempt to stop smoking, which is a most important step to improving health. Figure 13-2 shows the average rates of decline in function in smokers with COPD and nonsmokers. The earlier the rapid loss of function can be interrupted in the smoker, the greater will be the life expectancy.

Test: Spirometry before and after bronchodilator.

13B. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Even if the clinical diagnosis of COPD is clear-cut, it is important to quantify the degree of impairment of pulmonary function. A forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 50% of predicted portends future disabling disease. An FEV1 of less than 800 mL predicts future carbon dioxide retention (respiratory insufficiency).

Repeating spirometry every 1 to 2 years establishes the rate of decline of values such as the FEV1. The FEV1 declines an average of 60 mL/y in persons with COPD who continue to smoke, compared with 30 mL/y in normal subjects and persons with COPD who quit smoking.

FIG. 13-1. Progression of symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reflected by spirometry, arterial blood gas studies, and chest radiographs as a function of age in a typical case. Spirometry can detect COPD years before significant dyspnea occurs. (From Enright PL, Hyatt RE, eds. Office Spirometry: A Practical Guide to the Selection and Use of Spirometers. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1987. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.) |

FIG. 13-2. Normal decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) with age contrasted with the accelerated decline in continuing smoking in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Smoking cessation can halt this rapid decline. (From Enright PL, Hyatt RE, eds. Office Spirometry: A Practical Guide to the Selection and Use of Spirometers. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1987. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.) |

Tests:

1. Initially, spirometry before and after bronchodilator and determination of the diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO). Arterial blood gas studies are recommended when the FEV1 is less than 50% predicted.

2. Initially, if available, static lung volumes such as total lung capacity (TLC) and residual volume (RV).

3. Follow-up testing with spirometry is usually adequate.

13C. Asthma

It is important to be sure that the patient with apparent asthma really has this disease. Remember that “not all that wheezes is asthma.” Major airway lesions can cause stridor or wheezing, which has been mistaken for asthma. The flowvolume loop often identifies such lesions (see Section 2K, page 15).

Testing is also important in patients with asthma in remission or with minimal symptoms. This provides a baseline against which to compare results of function tests during an attack and thus quantify the severity of the episode.

The patient should be taught to use a peak flowmeter. He or she should establish a baseline of peak expiratory flows when asthma is in remission by measuring flows each morning and evening before taking any treatment. Then the patient should continue to measure and record peak flows on a daily basis.

PEARL: It is crucial that the patients be taught to use a peak flowmeter correctly. They must take a maximal inhalation, place their lips around the mouthpiece (a nose clip is not needed), and give a short, hard blast. They should avoid making a full exhalation; the exhalation should mimic the quick exhalation used to blow out candles on a birthday cake.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree