Recommendation 1: In children with PARDS requiring mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours, the causes that contribute to ongoing ventilator dependence should be systematically evaluated at least once daily. The goal is to reverse all possible ventilatory and nonventilatory issues impeding the ventilator discontinuation process

Recommendation 2: Children with PARDS receiving mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure should undergo a formal assessment of discontinuation potential if they meet the following criteria: a. The underlying cause for respiratory failure is likely reversed, b. their oxygenation and pH is acceptable, c. they are hemodynamically stabile, and d. their capacity to initiate spontaneous breaths is sufficient

Recommendation 3: Formal discontinuation assessments for children receiving mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure related to PARDS should be performed during spontaneous breathing rather than while the patient is still receiving substantial ventilator support. Tolerance of reduction to FiO2 < 50% and an initial brief period of spontaneous breathing can be used to assess the capability of continuing onto a formal spontaneous breathing trial (SBT). There are no firm criteria with which to assess patient tolerance during SBTs but the respiratory pattern, the adequacy of gas exchange, hemodynamic stability, and subjective comfort all should be considered. Children tolerating an SBT lasting 30–120 minutes should be considered for permanent ventilator discontinuation

Recommendation 4: Extubation (the removal of the artificial airway) from a child recovering from PARDS who has successfully passed an SBT should be based on assessments of airway patency and the ability of the patient to protect the airway. A patient should be assessed prior to extubation to determine if early initiation of NIV or HFNC may facilitate the transition to complete ventilator liberation

Recommendation 5: Children recovering from PARDS who are receiving mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure that fail an SBT should have the cause for the failed SBT determined. Once reversible causes for failure are corrected, subsequent SBTs should be performed once every 24 hours, or more frequently, if the cause is oversedation. After failing an SBT, they should receive a stable, nonfatiguing, and comfortable form of ventilatory support

Recommendation 6: Weaning and ventilator discontinuation and sedation management protocols designed to give nonphysician healthcare professionals more autonomy have been successfully developed and implemented in pediatric intensive care units and may facilitate ventilator discontinuation

Recommendation 7: Tracheostomy should be considered after an initial period of stabilization on the ventilator when it becomes apparent that a child recovering from PARDS will require prolonged ventilator assistance (>14–30 days). Tracheostomy then should be performed when the child appears likely to gain benefit and is still expected to require prolonged ventilator support. Children requiring high levels of sedation to tolerate an endotracheal tube and those with profound neuromuscular weakness should be considered for tracheostomy early, and reassessed daily with risk–benefit assessment

Recommendation 8: Unless there is evidence for clearly irreversible disease (e.g., high spinal cord injury or advanced neurodegenerative condition), a child recovering from PARDS requiring prolonged mechanical ventilator support for respiratory failure should not be considered permanently ventilator dependent until many months of ventilator liberation attempts have failed

Recommendation 9: Ventilator liberation strategies in children with PARDS requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation should be systematic, slow paced, and usually include gradually lengthening self-breathing trials

Recommendation 10: Transfer to a rehabilitation center specializing in weaning and providing high-level physical therapy may optimize the efficiency of the process of ventilator liberation in some children with PARDS

Although not formally applied, this stratification may be useful for categorizing ventilator discontinuation in children recovering from PARDS; proportionately, those with severe ARDS are more likely to be in the difficult or prolonged categories than children recovering from less severe lung injuries.

Assessing Readiness for Ventilator Discontinuation

Has the Severity of PARDS and Its Underlying Trigger Improved?

Strategies for providing lung protective mechanical ventilator support should be provided while aggressively treating the underlying disease process that triggered PARDS (e.g., infection, pancreatitis, aspiration, etc.). Once the patient achieves sufficient recovery, the process of discontinuing mechanical ventilatory support should begin. For practitioners following a PARDS management protocol, such as the one developed by the ARDS Clinical Research Network [7], which was modified by Curley et al. [8] for use in the pediatric prone positioning clinical trial, parameters for decreasing levels of ventilator support based on oxygenation and ventilation will be specified.

Is the Child Hemodynamically Stable?

Before attempting to discontinue mechanical ventilator support, pediatric patients should be hemodynamically stable. This may be defined as absence of clinically significant hypotension (i.e., requiring no vasopressor therapy or only low-dose) and active myocardial ischemia or its risk should have resolved. Although serum B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) – a marker of fluid overload, which can rise during an SBT due to left ventricular failure – has been used in clinical studies to guide fluid restriction and diuresis in adult patients [9], the majority of children with PARDS have recovered cardiovascular function by the time that ventilator weaning is initiated.

Is Gas Exchange Acceptable?

There are no strict parameters for categorizing when children are ready for ventilator discontinuation using gas exchange criteria, but assessing adequacy of gas exchange is important. Generally, children with SpO2 > 92% on an FIO2 ≤ 0.5 and PEEP ≤7 cm H2O have adequate oxygenation to initiate the process. Parameters for ventilation will vary but those with arterial pH is >7.35 (or venous pH >7.30) with an acceptable minute ventilation for age and weight can usually tolerate a trial. When high minute ventilation is required due to high dead space and/or high CO2 production, children may not be able to sustain this level for a prolonged period spontaneous breathing.

Is the Level of Sedation Titrated for the Child to Be Easily Awakened but Calm?

Before the process of ventilator discontinuation can proceed, the child must be able to consistently initiate spontaneous inspiratory efforts. The level of sedation commonly impedes this process [4]. Therefore, it is recommended that children tolerate a spontaneous awakening trial (SAT) before they undergo formal assessment of ability to tolerate ventilator discontinuation with an SBT [10]. Children are considered to have passed the SAT if they consistently open their eyes to verbal stimuli. If they do not, sedation should be decreased and then restarted at a decreased level (usually half the previous dose) and then titrated to achieve a prespecified sedation target (e.g., awake and calm) using a scale that is customized for children. The State Behavioral Scale is a validated customized sedation scale for children [11]. Use of short-acting sedatives, such propofol or dexmedetomidine, can be implemented fully or in part as part of sedative weaning as they do not impede spontaneous respiration as much as narcotics or benzodiazepines. However, prolonged use of propofol in children must be restricted due to the risk of propofol infusion syndrome [12]. Although use of a protocol for titrating narcotics and benzodiazepines in mechanically ventilated children, many of whom had PARDS, did not shorten time to extubation, overall, children on the protocol were more awake and had less overall narcotic exposure [13].

Is the Patient Profoundly Weak?

Respiratory muscle strength is also an important consideration. Children whose respiratory muscle strength is impeded due to critical illness myopathy/polyneuropathy or neurologic injury are at higher risk for extubation failure [14]. These patients should have their maximum airway pressure during airway occlusion (aPiMax) measured. In children with low aPiMax, considerations for need for prolonged mechanical ventilation and individualized weaning strategies are important.

Ventilator Weaning Strategies

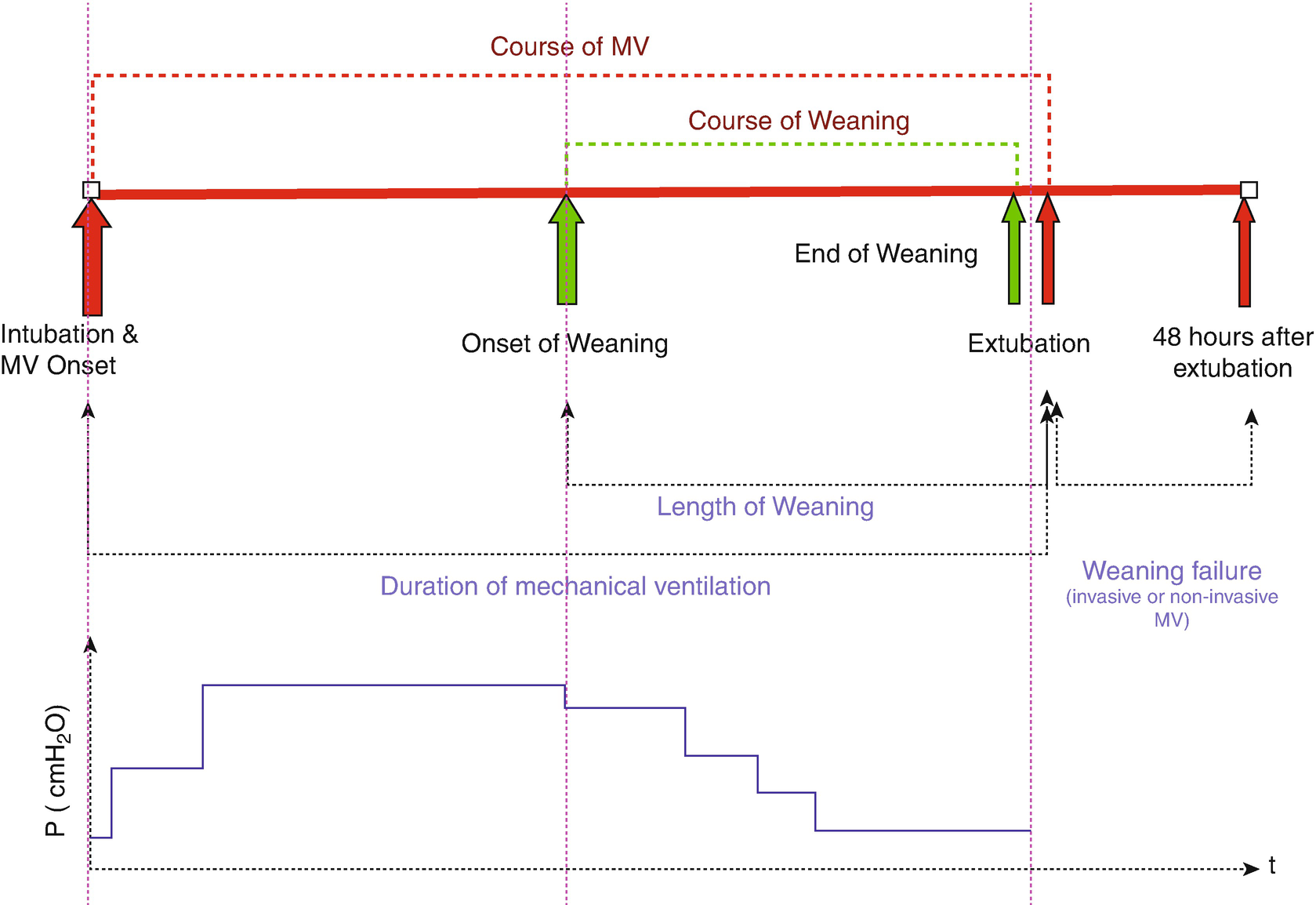

The course of mechanical ventilation in children. (Courtesy of Christopher Newth, MD and adapted from Newth et al. [15])

Example of a ventilator discontinuation protocol

There is no evidence to support a specific mechanical ventilator weaning method for children with PARDS, so continuous assessment is essential, with titration of the amount of support downward as the patient recovers. Randomized trials evaluating automated systems of weaning were systematically reviewed by Rose and colleagues [16], and there is some evidence that automated systems can reduce weaning duration significantly with a concomitant decrease in duration of mechanical ventilation and number of patients receiving a tracheostomy. Although these trials included patients with ARDS and pediatric trials were included, they were not focused specifically on this population. Therefore, an adequately powered multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of automated systems of weaning young children with PARDS.

Spontaneous Breathing Trials

In the 1990s, two randomized, controlled trials in adult patients were published [17, 18] that showed performing a once or twice daily SBT in patients meeting screening criteria enabled successful extubation in the majority of patients compared to synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) weaning (gradual reduction in mandatory breath rate) or PSV weaning. Most adult patients were successfully extubated after passing the first SBT, which was a finding that was replicated in children [4]. The two adult and pediatric studies included patients with ARDS. In patients that failed the initial SBT, no difference in duration of mechanical ventilation was seen between PSV versus usual care in children [4]. However, once or multiple daily SBT was superior to PSV and SIMV weaning in one multicenter randomized trial in adults [18]. This evidence shows that adult and pediatric patients who tolerate an SBT for 30–120 minutes should be considered for a trial of extubation, because they are likely ready for liberation from mechanical ventilator support.

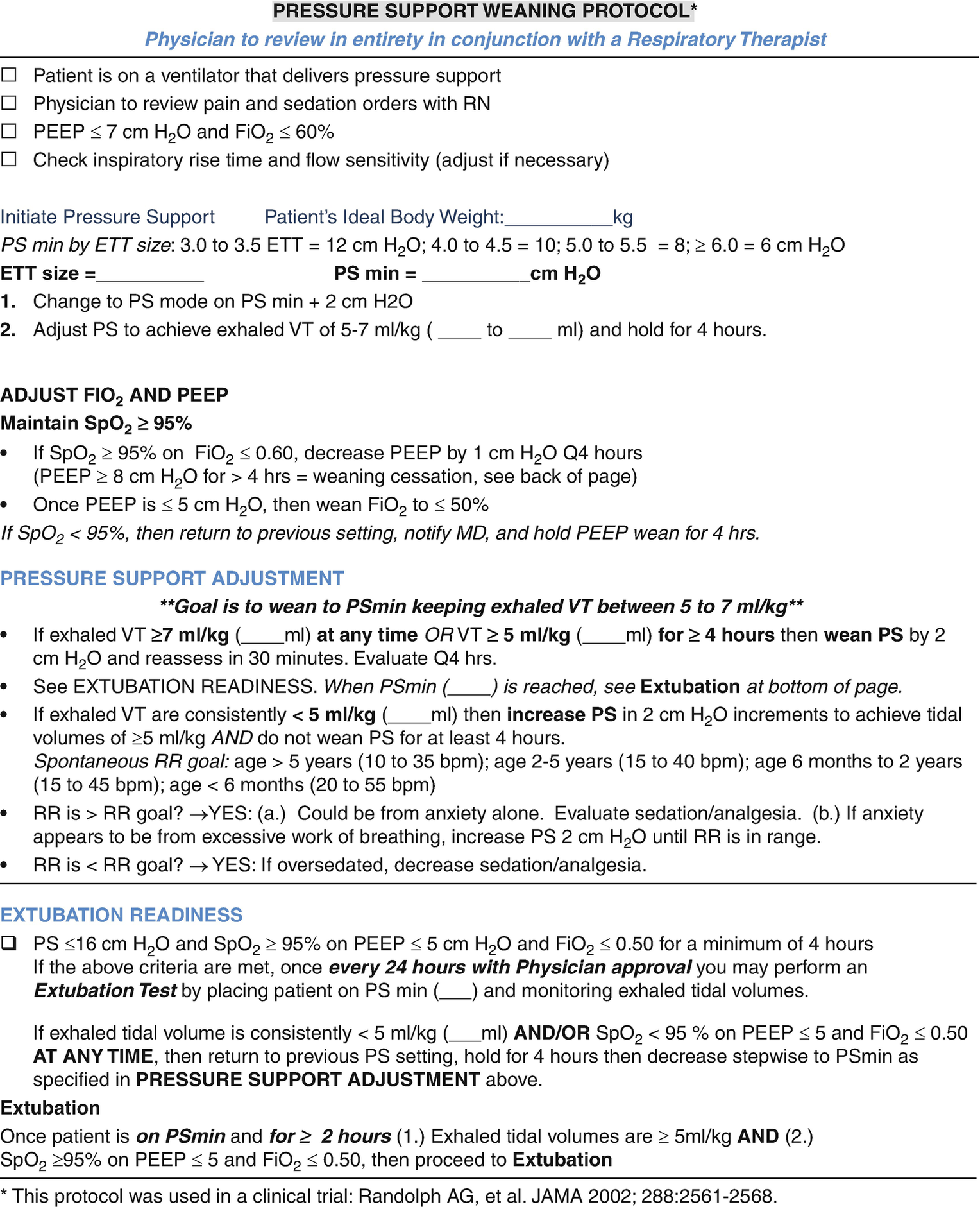

The resistance of an endotracheal tube is associated with its radius and length. Therefore, smaller tubes were believed to have higher resistance, necessitating that, along with the pressure needing to be generated against the ventilator valves, small children be supported with some PSV during their testing to decrease risk of fatigue and failure (Fig. 8.2). This belief has been challenged by Khemani and colleagues who showed that use of PSV may overestimate the patient’s chance of success by providing too much ventilator support and recommended use of CPAP alone for SBTs [19, 20]. In older patients, especially those with neuromuscular weakness or afterload-sensitive left ventricles, a T-piece trial can be used to estimate ability to tolerated extubation.

An SBT in children can be performed with a low level of PSV (5–10 cm H2O) titrated upward for smaller endotracheal tubes over low PEEP (4–5 cm H2O) as shown in the protocol in Fig. 8.2, or can be performed on CPAP of 5 cm H2O. Use of inspiratory pressure automatically titrated to overcome endotracheal tube resistance (i.e., tube compensation) is another option that is used in adult patients [2]. Tube compensation adjusts the level of PS according to the size of the endotracheal tube and inspiratory flow; it compensates for the resistance through the endotracheal tube. The resistance caused by upper airway edema after extubation may, however, be similar to the resistance caused by the endotracheal tube (ETT) [21].

In a multicenter study of 182 mechanically ventilated pediatric patients, an SBT (called an ERT or extubation readiness test) was performed for children meeting screening criteria as follows [4]. Patients were placed on PEEP ≤5 or FIO2 ≤ 0.5. If they maintained SpO2 > 94%, they were then converted to PS titrated to the size of the endotracheal tube (e.g., 3.0–3.5 mm, then PS = 10 cm H2O; ≥ 5.0 mm, then PS 6 cm H2O). The great majority of children passed the ERT, and of these, 88% were extubated with the great majority (87%), requiring no additional ventilator support. This finding was replicated using a similar protocol in the RESTORE study that was evaluating a sedation protocol in children mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure [13]. In children with an oxygenation index of six or lower, passing the ERT described above had a positive predictive value of 93% for successful extubation within 10 hours [22].

SBT Failure: Recognition and Management

Proposed criteria for ERT/SBT failure in children recovering from PARDS

Clinical criteria |

Diaphoresis Nasal flaring Increasing respiratory effort Tachycardia (increase in HR > 40 bpm) Bradycardia Cardiac arrhythmias Hypotension Apnea or hypopnea |

Laboratory criteria |

Increase of PetCO2 > 10 mmHg Decrease of arterial pH < 7.32 Decline in arterial pH > 0.07 PaO2 < 60 mmHg with an FiO2 > 0.40 (P/F O2 ratio <150) SpO2 / FiO2 declines >5% |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree