Warfarin is often used in patients with systolic heart failure (HF) to prevent adverse outcomes. However, its long-term effect remains controversial. The objective of this study was to determine the association of warfarin use and outcomes in patients with advanced chronic systolic HF without atrial fibrillation (AF), previous thromboembolic events, or prosthetic valves. Of the 2,708 BEST patients, 1,642 were free of AF without a history of thromboembolic events and without prosthetic valves at baseline. Of these, 471 patients (29%) were receiving warfarin. Propensity scores for warfarin use were estimated for each patient and were used to assemble a matched cohort of 354 pairs of patients with and without warfarin use who were balanced on 62 baseline characteristics. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to estimate the association between warfarin use and outcomes during 4.5 years of follow-up. Matched participants had a mean age ± SD of 57 ± 13 years with 24% women and 24% African-Americans. All-cause mortality occurred in 30% of matched patients in the 2 groups receiving and not receiving warfarin (hazard ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.62 to 1.19, p = 0.361). Warfarin use was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio 0.97, 95% confidence interval 0.68 to 1.38, p = 0.855), or HF hospitalization (hazard ratio 1.09, 95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.44, p = 0.568). In conclusion, in patients with chronic advanced systolic HF without AF or other recommended indications for anticoagulation, prevalence of warfarin use was high. However, despite a therapeutic international normalized ratio in those receiving warfarin, its use had no significant intrinsic association with mortality and hospitalization.

Heart failure (HF) is a hypercoagulable state, and patients with HF and low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) may be at increased risk of LV thrombus formation and thromboembolic events. Although use of anticoagulants is recommended in patients with HF and atrial fibrillation (AF) and/or a previous thromboembolic event, there is conflicting evidence of the benefit of anticoagulation use in patients with HF without AF and/or previous thromboembolic events. However, because risk of LV thrombus formation increases with decreasing LVEF, clinicians are often concerned about the risk of LV thrombus formation in their patients with HF and markedly low LVEF. The objective of the present study was to determine the association of warfarin use and outcomes in patients with advanced chronic systolic HF without AF and/or previous thromboembolic events.

Methods

We conducted a post hoc analysis of the public-use copy of the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) data for the present study. The BEST was a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of bucindolol, a β blocker, in HF, the methods and results of which have been previously published. Briefly, 2,708 patients with advanced chronic systolic HF were enrolled from 90 different sites across the United States and Canada from May 1995 to December 1998. All but 1 patient consented to be part of the public-use copy of the data. At baseline, patients had a mean duration of 49 months of HF and had a mean LVEF of 23%. All patients had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III to IV symptoms and >90% of all patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, and digitalis.

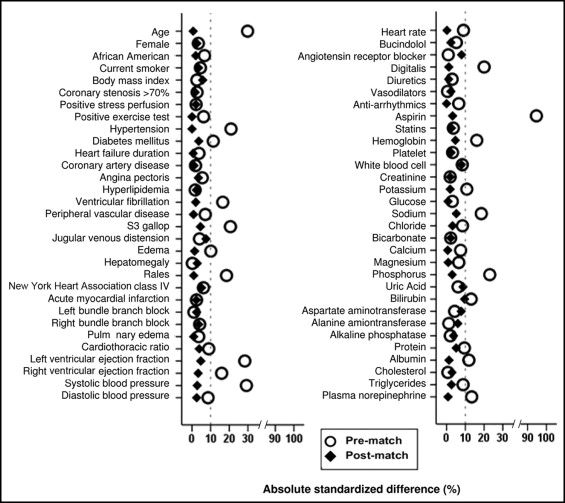

Data on use of warfarin at baseline were available in all 2,707 participants. For the present analysis, we excluded 692 patients with AF, 343 patients with a history of thromboembolic diseases, and 30 patients with prosthetic valves at baseline. Thus, our final sample was 1,642, of which 471 patients (29%) were receiving warfarin at baseline. Considering the significant imbalances in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups ( Table 1 ), we used propensity scores to assemble a matched cohort of 354 pairs of patients who were well balanced on 62 baseline characteristics. Propensity scores for warfarin use were estimated for each of the 1,642 patients using a nonparsimonious multivariable logistic regression model. Absolute standardized differences were estimated to evaluate the prematch imbalance and postmatch balance and presented as a Love plot. An absolute standardized difference of 0% indicates no residual bias and differences <10% are considered inconsequential.

| Variable | Before Propensity Matching | After Propensity Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No warfarin (n = 1,171) | Warfarin (n = 471) | p Value | No warfarin (n = 354) | Warfarin (n = 354) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 12 | 56 ± 12 | <0.001 | 57 ± 14 | 57 ± 12 | 0.353 |

| Women | 283 (24%) | 107 (23%) | 0.532 | 87 (25%) | 83 (23%) | 0.781 |

| African-American | 302 (26%) | 108 (23%) | 0.226 | 84 (24%) | 87 (25%) | 0.857 |

| Current smoking | 213 (18%) | 94 (20%) | 0.406 | 73 (21%) | 68 (19%) | 0.709 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 37 ± 9 | 37 ± 8 | 0.643 | 37 ± 9 | 37 ± 8 | 0.446 |

| New York Heart Association class III | 1,086 (93%) | 429 (91%) | 0.255 | 322 (91%) | 327 (92%) | 0.583 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Heart failure duration (months) | 46 ± 48 | 44 ± 44 | 0.505 | 45 ± 47 | 45 ± 45 | 0.939 |

| Coronary artery disease | 670 (57%) | 265 (56%) | 0.724 | 190 (54%) | 192 (54%) | 0.937 |

| Angina pectoris | 624 (53%) | 238 (51%) | 0.312 | 172 (49%) | 178 (50%) | 0.708 |

| Hypertension | 715 (61%) | 239 (51%) | <0.001 | 191 (54%) | 191 (54%) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 452 (39%) | 156 (33%) | 0.038 | 124 (35%) | 118 (33%) | 0.693 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 527 (45%) | 208 (44%) | 0.756 | 145 (41%) | 149 (42%) | 0.825 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 79 (7%) | 54 (12%) | 0.002 | 31 (9%) | 33 (9%) | 0.896 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 164 (14%) | 78 (17%) | 0.186 | 53 (15%) | 52 (15%) | 1.000 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Bucindolol | 600 (51%) | 229 (49%) | 0.337 | 168 (48%) | 172 (49%) | 0.821 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker | 1,137 (97%) | 458 (97%) | 0.875 | 340 (96%) | 345 (98%) | 0.425 |

| Digitalis | 1,056 (90%) | 449 (95%) | 0.001 | 333 (94%) | 334 (94%) | 1.000 |

| Diuretics | 1,086 (93%) | 433 (92%) | 0.573 | 326 (92%) | 327 (92%) | 1.000 |

| Vasodilators | 504 (43%) | 204 (43%) | 0.920 | 146 (41%) | 150 (42%) | 0.818 |

| Aspirin | 738 (63%) | 98 (21%) | <0.001 | 91 (26%) | 96 (27%) | 0.640 |

| Statins | 273 (23%) | 117 (25%) | 0.511 | 87 (25%) | 83 (23%) | 0.794 |

| Physical examination | ||||||

| Pulse (beats/min) | 82 ± 13 | 83 ± 13 | 0.100 | 83 ± 13 | 83 ± 13 | 0.979 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 119 ± 19 | 114 ± 16 | <0.001 | 115 ± 16 | 115 ± 16 | 0.708 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 72 ± 11 | 71 ± 11 | 0.114 | 72 ± 11 | 71 ± 11 | 0.738 |

| Jugular venous distention | 399 (42%) | 836 (48%) | 0.003 | 134 (38%) | 147 (42%) | 0.356 |

| S3 gallop | 477 (41%) | 240 (51%) | <0.001 | 165 (47%) | 173 (49%) | 0.582 |

| Pulmonary rales | 162 (14%) | 38 (8%) | 0.001 | 36 (10%) | 35 (10%) | 1.000 |

| Hepatomegaly | 115 (10%) | 46 (10%) | 0.973 | 36 (10%) | 39 (11%) | 0.807 |

| Edema | 288 (25%) | 96 (20%) | 0.068 | 76 (22%) | 74 (21%) | 0.924 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 14.2 ± 1.6 | 0.003 | 14.0 ± 1.6 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 0.522 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.722 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.808 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.34 ± 0.46 | 4.29 ± 0.47 | 0.046 | 4.31 ± 0.47 | 4.31 ± 0.46 | 0.807 |

| Plasma norepinephrine (pg/ml) | 484 ± 272 | 524 ± 321 | 0.011 | 511 ± 325 | 509 ± 302 | 0.917 |

| Partial thromboplastin time (seconds) | 28 ± 8 | 34 ± 8 | <0.001 | 29 ± 13 | 34 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Left bundle branch block by electrocardiogram | 303 (26%) | 124 (26%) | 0.850 | 98 (28%) | 94 (27%) | 0.796 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio by chest x-ray | 54.8 ± 7.2 | 55.5 ± 6.9 | 0.101 | 55.1 ± 7.3 | 55.4 ± 6.9 | 0.590 |

| Pulmonary edema by chest x-ray | 114 (10%) | 51 (11%) | 0.505 | 37 (11%) | 36 (10%) | 1.000 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction by nuclear scan (%) | 23.5 ± 7.2 | 21.4 ± 7.3 | <0.001 | 22.4 ± 7.5 | 22.1 ± 7.2 | 0.520 |

| Right ventricular ejection fraction by nuclear scan (%) | 35.5 ± 11.7 | 33.6 ± 12.5 | 0.003 | 33.7 ± 11.9 | 34.1 ± 12.4 | 0.660 |

BEST participants were followed for a minimum of 18 months and a maximum of 4.5 years. Primary outcome for the present analysis was all-cause mortality during 4.1 years of follow-up (mean 2, range 10 days to 4.14 years). Secondary outcomes were cardiovascular and HF mortalities and all-cause and HF hospitalizations. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to determine associations between warfarin use and outcomes during 4.1 years of follow-up. Log-minus-log scale survival plots were used to check proportional hazards assumptions. Subgroup analyses were conducted to determine the homogeneity of association between use of warfarin and all-cause mortality. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with a p value <0.05 considered statistically significant. All data analyses were performed using SPSS 18 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Matched patients had a mean age ± SD of 57 ± 13 years, 170 ± 24% were women, and 171 ± 24% were African-Americans. Before matching, patients receiving warfarin were younger, had a lower mean of LVEF and right ventricular EF, a lower prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, but had a greater symptom burden such as jugular venous distention and S3 gallop. These and other imbalances in baseline characteristics were well balanced after matching ( Figure 1 , Table 1 ). After matching, absolute standardized differences for all measured covariates were <10% (most were <5%), suggesting substantial covariate balance across groups ( Figure 1 ). Median international normalized ratios (INRs; interquartile range) were 2.0 (1.1) and 1.0 (0.1) for matched patients receiving and not receiving warfarin, respectively.