In 1994, we reported in The American Journal of Cardiology that a simple anthropometric measurement, waist circumference, was related to the amount of abdominal visceral adipose tissue measured by computed tomography. An elevated waist circumference was also found to be associated with several features of the cardiometabolic risk profile such as glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, and an atherogenic dyslipidemic profile that included hypertriglyceridemia and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Although a linear relation was found between waist circumference and these metabolic alterations, we reported that a waist circumference value of about 100 cm was associated with a high probability of finding diabetogenic and atherogenic abnormalities. The present short report provides a brief update of issues that have been raised regarding the measurement of waist circumference and its clinical use over a period of 20 years since the original publication.

Although obesity is generally perceived as a health hazard, it remains an ill-defined clinical entity. For instance, the term “metabolically healthy” obesity has even been coined to describe a subgroup of obese patients not characterized by the expected metabolic complications of excess body weight or fat. There is also an obesity paradox in cardiology: obese patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) appear to have a better survival compared with patients with CVD with an apparently normal body weight. Thus, the clinical relevance of assessing adiposity in CVD risk assessment remains debated.

In the late 80s, we reported that there was an independent association between abdominal visceral adiposity (measured at that time by computed tomography) and cardiometabolic outcomes such as glucose tolerance, circulating insulin levels, and an atherogenic dyslipidemic profile. On that basis, we proposed in 1990 that visceral obesity could represent the form of overweight or obesity associated with the highest risk of CVD.

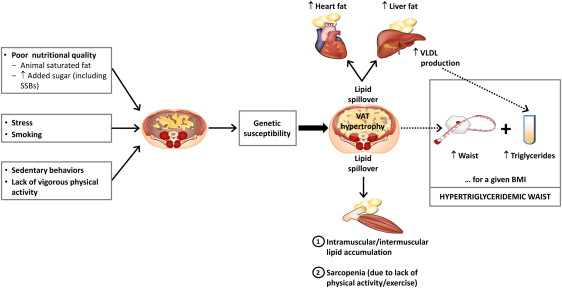

Several additional alterations were later added to the constellation of metabolic complications found in subjects with an excess of abdominal visceral fat. Since then, groups that have used imaging technologies (initially computed tomography and then magnetic resonance imaging) also came to the conclusion that an excess of visceral adipose tissue was indeed associated with atherogenic and diabetogenic metabolic complications. A consensus has emerged over the last 25 years that visceral obesity represents a form of overweight or obesity associated with dysfunctional subcutaneous adipose tissue, with ectopic fat deposition in lean tissues such as the heart, the liver, and the skeletal muscle, as well as with a state of inflammation and insulin resistance, all these alterations contributing to the development of a constellation of atherogenic and diabetogenic metabolic abnormalities ( Figure 1 ).

As imaging was not a realistic option for widespread clinical use, there was a need to develop simple anthropometric tools to improve the identification of subjects with excess abdominal visceral adipose tissue. That was the rationale for a simple analysis that we published 20 years ago in the March 1994 issue of The American Journal of Cardiology . In that report, we showed that waist circumference and the sagittal diameter (the thickness of the abdomen from back to front) were crude but useful correlates of the absolute amount of visceral adipose tissue. This report has been widely cited since its publication and has probably contributed to the widespread recommendation of measuring waist girth in clinical practice.

Over this period of 20 years, several legitimate critiques have been raised to the use of waist circumference as a vital sign. First, because of its association with the amount of abdominal visceral fat, waist circumference has often been considered by some as a proxy for visceral adiposity assessed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. However, the shared variance is only in the range of 50% to 75%. Thus, waist circumference alone cannot perfectly discriminate a large waistline resulting from excess abdominal subcutaneous adiposity from increased visceral adiposity. In 2000, we suggested that an elevated waistline combined with increased plasma triglyceride levels could help identify subjects with visceral obesity: The “hypertriglyceridemic waist” phenotype was born. Since this publication, a stream of studies has confirmed that subjects with hypertriglyceridemic waist were not only characterized by metabolic abnormalities but were also at increased risk of coronary heart disease compared with subjects with an elevated waistline but with normal plasma triglyceride levels ( Figure 1 ).

However, waist circumference used in isolation is also an index of total body fat. The correlation between the body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference at the population level is rather strong (in the area of r = 0.85). Thus, when considered as a single anthropometric index, waist circumference most often barely outperforms the BMI as a predictor of CVD risk. However, we have previously made the point that waist circumference is a useful discriminant of cardiometabolic risk when the patient’s BMI is known. A simple clinical example of the limitation of waist circumference used in isolation is the following. Let’s compare two 50-year old male patients with similar waistline values (both have a waistline of 103 cm) but differing BMIs: the first has a BMI of 26 kg/m 2 , whereas the second has a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 . It is clear that the patient with BMI 26 kg/m 2 is abdominally obese with presumably less muscle mass than the patient with BMI 30 kg/m 2 , who is probably overall obese with possibly a greater lean body mass. This example illustrates the need to interpret any given waist circumference value in the context of the BMI. Are we there yet? Not quite. However, a recent large analysis from the Mayo Clinic involving >650,000 subjects followed up for an average of 9 years has clearly shown that, within each BMI category examined, there was a continuous increase in mortality risk associated with a progressive increase in waist circumference.

Thus, both waist circumference and the BMI should be measured in clinical practice. A systematic review by a panel of experts has also concluded that although the absolute waist circumference value measured on a given subject depends on the position where the measurement is obtained (narrowest waist, mid-distance between bottom of rib cage to top of iliac crest, top of iliac crest, and umbilicus), all measurements were found to essentially show similar associations with clinical outcomes. Because of its simplicity, the panel also recommended the use of a single bone landmark (top of the iliac crest) to measure waist circumference. We have since launched an educational website on abdominal obesity ( www.myhealthywaist.org ) visited by individuals from 168 countries where health professionals and patients can download a step-by-step animation on how to measure waist circumference.

Which waist circumference value is associated with increased health risk? Because of the importance of abdominal obesity in its etiology, waist circumference was recognized as a key criterion for the clinical diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome. However, the waist cutoffs initially proposed for men (102 cm) and women (88 cm) were values corresponding to a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 in men and women, respectively. Since then, it has been recognized that in genetically susceptible subjects and in some ethnic groups such as Asians and South Asians (more prone to complications at lower BMI values), waist circumference values lower than those proposed for Caucasians are associated with increased cardiometabolic risk.

Finally, when a patient meets the clinical criteria of the metabolic syndrome, a reduction in waist circumference should be targeted. Lifestyle modification studies that have focused on improving nutritional quality and increasing physical activity or exercise have reported a reduction in the participants’ waist circumferences, even in those not losing much weight as some of them may even gain muscle mass when becoming regularly active. Diabetes prevention studies have shown that a reduction of about 4 cm in waist circumference was associated with a substantial reduction (almost 60%) in the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in high-risk subjects with impaired glucose tolerance.

Twenty years later, waist circumference as an additional marker of health risk has survived the passage of time, and this anthropometric index is certainly as present in the clinical and/or scientific literature as the famous BMI promoted by Keys in 1972. A large waistline for a given BMI value is a simple and useful clinical marker of excess visceral adiposity or ectopic fat, particularly in the presence of increased circulating triglyceride levels. On that basis, waist loss (with or even without weight loss) may eventually become a useful target when reshaping the nutritional and physical activity or exercise habits of high-risk sedentary abdominally obese patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree