Chapter 5

Visceral Artery Stenosis and Mesenteric Ischaemia

Daryll Baker

Department of Vascular Surgery, Royal Free Hospital, UK

Introduction

Visceral artery disease is the narrowing of the arteries that supply blood to the intestines, spleen and liver. The visceral arteries are coeliac axis (CA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). This disease process presents most commonly as two separate syndromes, acute mesenteric ischaemia (AMI) and chronic mesenteric ischaemia (CMI), although asymptomatic disease is common (20% of the older population) and chronic disease can present acutely.

Acute mesenteric ischaemia

Definition

AMI results from the sudden reduction in intestinal blood supply so severe as to result in bowel infarction.

Epidemiology

AMI occurs in 0.1% of hospital admissions, mainly in the older age group. It is associated with a greater than 70% mortality rising to 90% if bowel infarction has occurred. This can only be reduced with rapid vascular intervention, although the long-term prognosis remains grave with a 50% five-year survival rate.

Aetiology

Table 5.1 summarises the common causes of AMI. It arises primarily from problems in the SMA circulation or its venous outflow. Arterial disease may be due to occlusion of the SMA either from an embolus (50%) or from thrombosis of a pre-existing atherosclerotic lesion (25%). Arterial vasospasm can severely reduce mesenteric perfusion (20%) and mesenteric venous thrombosis can also cause bowel ischaemia (10%).

Table 5.1 Common causes of acute mesenteric ischaemia.

| Mesenteric embolic causes |

|

| Thrombosis of pre-existing plaques |

|

| Mesenteric vasospasm |

|

| Mesenteric vein thrombosis |

|

AMI does not include ischaemia caused by localised mechanical compression such as strangulated hernia, volvulus or intussusception.

Clinical presentation

The initial presentation of AMI is usually non-specific and diagnosis is therefore often missed initially, resulting in the significantly high mortality. A high clinical index of suspicion is vital in patients with the following presentation:

- Abdominal pain (95%). This is usually sudden and disproportionate to physical findings. Typically, the pain is moderate to severe, diffuse, non-localized and constant. It may be unresponsive to opiates, but peritonitic findings are often absent

- Gut emptying. Vomiting and diarrhoea (75%)

- Abdominal distension (25%)

- As the bowel becomes gangrenous, rectal bleeding and sepsis develops

- Clinical presentations that hint at an aetiology include:

- Atrial fibrillation or a recent myocardial infarction point to an embolic aetiology.

- Previous chronic mesenteric ischaemic symptoms (see the following sections) are present in 50% of patients with thrombotic AMI.

- Arterial vasospasm and mesenteric ischaemia tend to occur in older patients already unwell in the intensive care unit.

- In patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis, the abdominal pain tends to be less dramatic and can last for some weeks (30% have symptoms >30 days) and most have more than one risk factor for thromboembolic disease.

- Atrial fibrillation or a recent myocardial infarction point to an embolic aetiology.

Investigations

Blood tests are not helpful in diagnosing AMI and tend to reflect developing bowel infarction, such that the white cell count and lactate levels are elevated and metabolic acidosis develops late in the clinical course. Elevated amylase levels are non-specific and phosphate levels are of no help.

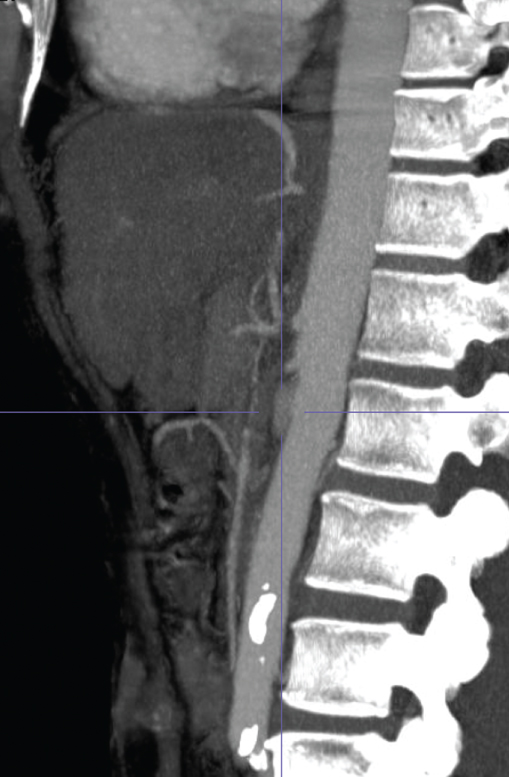

If there is suspicion of AMI, radiographic studies should be undertaken without waiting for blood results. CT angiography is recommended as a first-line investigation as it has a greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing AMI. It will confirm the diagnosis and aid in planning treatment (Figure 5.1). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) yields findings similar to those of CT scanning in AMI (sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 91%). It is particularly effective for evaluating mesenteric vein involvement. Therefore, it may be used in preference to CT depending on local radiological expertise. Plain abdominal X-rays and non-contrast CT help exclude other causes of the abdominal pain but identify AMI only when bowel infarction has developed. Duplex ultrasound is not usually performed in AMI as dilated loops of bowel reduce accuracy.

Figure 5.1 CT angiogram showing the aorta in front of the spine and occluded ostia of the mesenteric vessels.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis is made, the treatment should be initiated without delay. The patient should have active resuscitation as per hospital protocol for critically ill patients with a low threshold for involving the intensive care team. Intravenous fluid resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products should be started promptly to restore volume. Haemodynamic monitoring should be instituted with central venous pressure measurements and assessment of urinary output. Optimise cardiac status by treating any arrhythmia or congestive heart failure and providing inotropic support as required, but avoiding use of vasopressors. Ensure adequate tissue oxygenation by maintaining a saturation of over 95%, by endotracheal intubation and ventilation if necessary. The patient should receive adequate analgesia and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics should be commenced. Heparin anticoagulation is started as soon as the diagnosis has been made and before an urgent treatment plan has been determined. For venous AMI, this is often the only treatment required.

Revascularisation can be achieved by two methods: endovascular interventions or by open surgery involving a laparotomy.

Table 5.2 Potential complications of endovascular mesenteric revascularisation.

| Dissection of mesenteric arteries |

| Rupture of mesenteric arteries. Small perforation can be covered with a stent graft, but larger ones require open surgery |

| Embolisation of atherosclerotic plaques causing bowel infarction |

| Groin haematoma |

| Acute limb ischaemia |

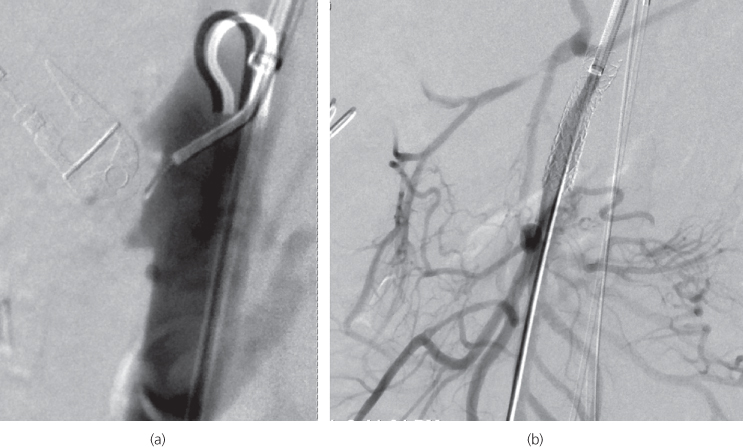

Endovascular interventions are best undertaken in a hybrid operating theatre (Figure 5.2) in combination with open surgical procedures where potential complications (Table 5.2) can often be better managed. Thrombolytic agent infusion through an angiography catheter is considered when bowel infarction has not yet occurred. Bleeding is the main complication with use of thrombolysis. Angioplasty (after thrombolysis) with stent placement is indicated if the guide wire can cross the stenosis. Owing to the anatomy of the SMA, angioplasty and stenting (Figure 5.3) are technically easier if a brachial approach is used. Suction embolectomy is not used as it often fails.

Figure 5.2 Complex vascular interventions are best done in a ‘hybrid’ theatre where both open and endovascular interventions can be performed.

Figure 5.3 Endovascular management of a superior mesenteric artery occlusion. (a) Catheter angiogram demonstrating that all mesenteric vessels are occluded at the origin. (b) The superior mesenteric artery occlusion has been treated by angioplasty and stenting. A completion angiogram reveals good mesenteric blood supply.

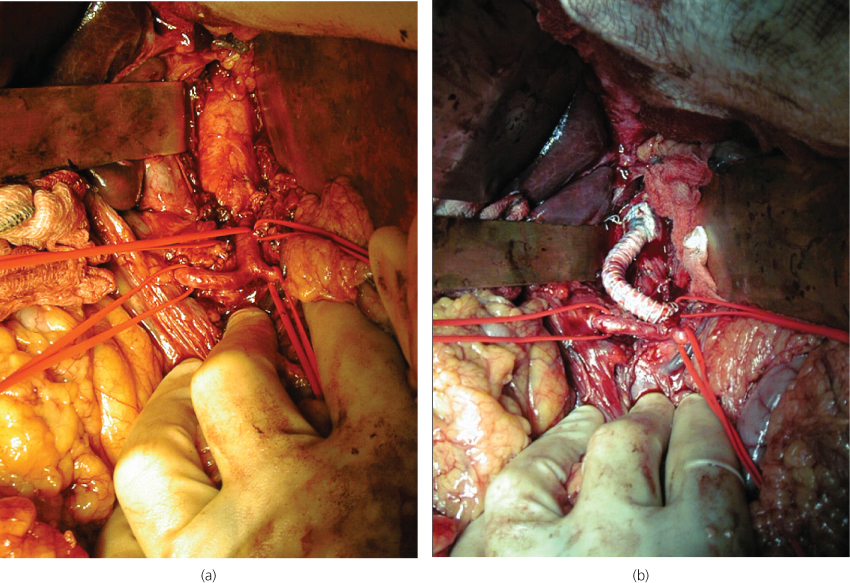

A laparoscopy may be perfumed to assess the viability of the bowel following a successful endovascular intervention. If there is evidence of irreversible bowel ischaemia, then a laparotomy is required to resect the necrotic bowel. Determination of bowel viability is difficult and the practice of viewing the bowel through a Wood lamp following fluorescein administration has not been universally adopted. Therefore, it is best to resect all areas of obviously necrotic bowel (Figure 5.4) and consider a ‘second-look’ laparotomy at 24–48 hours when the bowel has had sufficient time to recover and resected bowel ends can be anastomosed.

Figure 5.4 At laparotomy for acute mesenteric ischaemia (AMI), a bowel that is obviously infarcted needs to be resected. However, it is often difficult to determine the viability of the bowel as seen in this photo and a ‘second-look’ laparotomy should always be considered in such cases.

The open surgical approach involves performing an embolectomy to revascularise the ischaemic bowel. The SMA is isolated by palpating lateral to the aorta at the root of the lifted transverse colon mesentery, and because most emboli are near the origin of the middle colic artery, the pulse can be felt. A transverse arteriotomy is made proximal to the point of occlusion, and a balloon-tipped Fogarty catheter (size 3) passed distally. Often, a vein patch is needed to repair the arteriotomy. The small bowel should ‘pink-up’ within 10 minutes and a pulse felt or heard with the intra-operative Doppler machine. A bypass graft may be required if the bowel is not gangrenous and the cause is not embolic. An antegrade aorto-mesenteric bypass is performed using a reversed long saphenous vein (harvested from the upper thigh), as some form of faecal bacterial contamination is likely and insertion of a prosthetic risks infection.

Follow-up

Patients requiring extensive small bowel resection require follow-up by a gastroenterologist. Patients initially have severe diarrhoea but may be able to compensate after a few months with reduced loose bowel motions and begin to put on weight. Some patients have insufficient remnant small bowel and require total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The ileus secondary to intestinal ischaemia can cause adhesions and subsequent bowel obstruction. Patients who have had mesenteric vein thrombosis or are in atrial fibrillation will require warfarin therapy for life. Any cardiovascular risk factor should also be addressed in these patients.

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia (mesenteric angina)

Definition

The main symptom of CMI is mesenteric angina. This is significant postprandial pain that occurs due to extensive mesenteric vascular occlusive disease such that blood flow cannot increase enough to meet the visceral metabolic demands associated with digestion.

To produce such symptoms, at least two of the three mesenteric arteries need to be occluded as there is a vast network of collateral blood vessels linking them.

Epidemiology

The aetiology is almost always atherosclerotic stenotic disease. Those affected have multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerotic involvement of other territories such as coronary arteries, peripheral arterial disease and cerebrovascular disease. It is seen mainly in middle aged and elderly people and is three times more common in women. If not treated, the patient will suffer a painful death.

Clinical presentation

Patients classically complain of dull, postprandial epigastric pain, usually within the first hour after a meal. It gradually increases in intensity, reaches a plateau, and then slowly decreases in intensity several hours after eating. Initially, the pain develops only after large meals, but as the disease progresses, even small meals are poorly tolerated. The pain is out of proportion with the physical examination findings. Very commonly patients experience weight loss (80%) and often develop food aversion (sitophobia). Motility disturbances such as diarrhoea, bloating and vomiting can also be present. Physical examination reveals evidence of weight loss with signs of malnutrition and sometimes tenderness without rebound during episodes of pain. These patients may have bruits on auscultation of visceral arteries and also have reduced lower limb pulses.

Investigations

With these symptoms, a malignancy is often suspected that delays making the true diagnosis on average by 18 months. Blood tests do not help with making the diagnosis of CMI. They do, however, give an indication of the severity of the associated malnutrition. Duplex ultrasonography of the mesenteric vessels is a useful initial test in the clinic setting if the diagnosis is suspected. It is technically difficult but can be accomplished in around 85% of cases. CTA (or MRA) is recommended if duplex ultrasound is equivocal or for planning surgical intervention. In most cases, this will show that two of the three mesenteric vessels are occluded and the third is often severely stenosed. There will be an enlarged ‘meandering’ mesenteric marginal artery (of Drummond) acting as a collateral supply. Catheter-based angiography is indicated only during endovascular intervention.

Treatment

The indication for treatment is symptoms associated with mesenteric vessel occlusions. Asymptomatic lesions are not treated. There is no effective medical treatment but patients benefit from being on antiplatelet and statin therapy to reduce their long-term cardiovascular risk. Intervention for CMI is urgent rather than emergency and, therefore, can be planned and the patient’s cardiovascular co-morbidities optimised. TPN feeding while this is being undertaken will help counter some of the peri-operative detrimental effects of malnutrition. Revascularisation of the gut is by either endovascular or open surgical techniques.

Endovascular surgical interventions are best undertaken in a hybrid theatre (Figure 5.2) under general anaesthetic as the potential complications may require open surgery (Table 5.2).

Vascular surgical intervention options include

- bypass jump grafting, using either a vein or a prosthetic graft (Figure 5.5), and

- endarterectomy—surgical removal of the plaque.

Figure 5.5 A laparotomy has been performed to deal with an occluded coeliac artery. (a) Coeliac artery and its early branches have been exposed. (b) A synthetic jump bypass graft has been performed from the aorta to the celiac artery past the occlusion.

It is usual practice to try and revascularise at least two of the three vessels. Treatment approach adopted will depend on the local facilities and expertise, as well as the general health of the patient and their associated co-morbidities. Compared to open surgery, an endovascular approach is considered to be less invasive with lower intra-operative mortality rates (6% versus 12%) and is associated with a shorter hospital stay (3 days versus 12 days), but with a lower long-term durability (30% versus 66% 3-year symptom-free outcome).

Follow-up

Patients who survive surgical revascularisation tend to do well, with excellent long-term prognosis (5-year survival rates approach 80%). Regular follow-up review includes duplex ultrasound and MRI (rather than CTA to reduce radiation exposure) to assess for re-stenosis. However, as the proper management of asymptomatic re-stenosis is unclear, further intervention should only be considered with the recurrence of symptoms, thus achieving an 80% 5-year symptom-free rate.

Conclusions

Symptomatic mesenteric ischaemia is a relatively rare but a potentially life-threatening disorder with very poor outcomes. An early diagnosis remains the key challenge in both AMI and CMI and requires a high index of suspicion in patients presenting with abdominal pain who have significant cardiac disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Outcomes in this condition can only be improved by rapid diagnosis and treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree