Viruses, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia

Viruses, mycoplasma, and chlamydia are common and important causes of lower respiratory tract infection and may result in tracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia. Viral pneumonia in adults can be divided into two broad categories: So-called atypical pneumonia in otherwise normal hosts and viral pneumonia in immunocompromised patients (1). Atypical pneumonia can be due to viruses, mycoplasma, and chlamydia. Viruses account for approximately 10% to 20% of community-acquired pneumonias (2,3,4). Most viral pneumonias in immunocompetent adults are due to influenza virus; other common viral etiologies include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and adenovirus. Immunocompromised hosts are particularly susceptible to pneumonias caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes viruses.

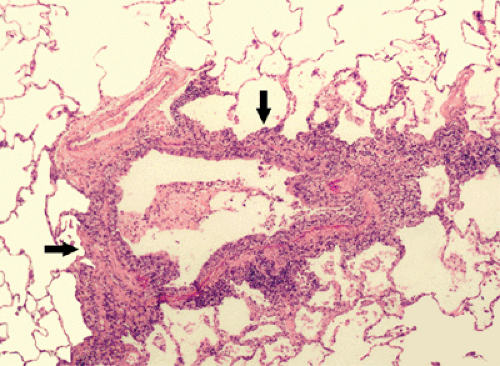

Infection by viruses, mycoplasma, and chlamydia is usually acquired through the airways. Because the organisms replicate within tissue cells, the most prominent histologic changes are seen in the epithelium and adjacent interstitial tissue (5). Bronchiolitis is manifested histologically by a neutrophilic exudate in the airway lumen and a predominantly mononuclear infiltrate in its wall (see Fig. 5.1) (5). Parenchymal involvement is typically that of bronchopneumonia. It initially involves the lung adjacent to the terminal and respiratory bronchioles resulting in poorly defined peribronchiolar airspace nodules of 4 to 10 mm diameter (see Fig. 5.2). The pneumonia typically extends from a peribronchiolar distribution to involve the entire secondary lobule resulting in lobular consolidation, a characteristic histologic feature of bronchopneumonia (see Fig. 5.3) (5).

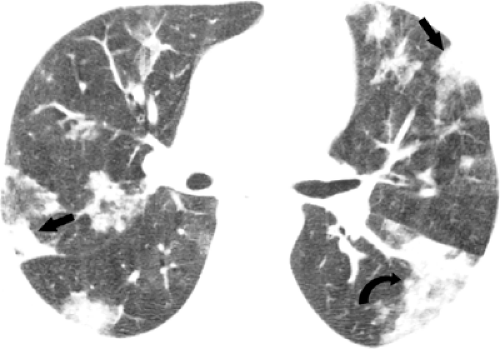

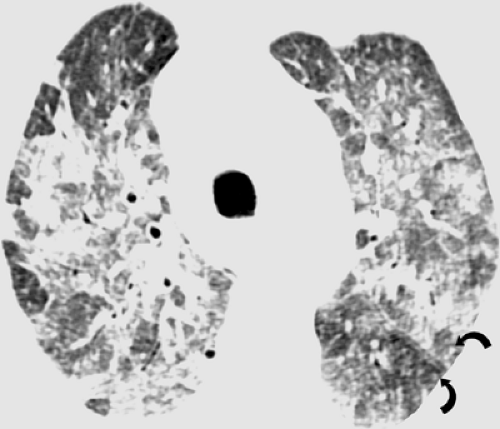

The bronchiolar and peribronchiolar inflammation is initially reflected by the presence of a small nodular or reticulonodular pattern on the radiograph and centrilobular nodules and branching opacities (tree-in-bud pattern) on high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan (see Fig. 5.4) (1,5,6,7). Bronchiolitis may be associated with partial airway obstruction resulting in areas of air

trapping and hyperinflation. Airway obstruction may be the predominant or the only clinical and radiologic finding of bronchiolitis in infants and young children but is relatively uncommon in adults (1,5,6,7). Extension of the inflammatory process into the adjacent parenchyma results in 4 to 10 mm diameter centrilobular airspace nodules. These small foci of disease may progress to lobular, subsegmental, or segmental areas of consolidation characteristic of bronchopneumonia (see Fig. 5.5) (1,5,6,7). Partial filling of the airspaces results in ground-glass opacities (Fig. 5.5).

trapping and hyperinflation. Airway obstruction may be the predominant or the only clinical and radiologic finding of bronchiolitis in infants and young children but is relatively uncommon in adults (1,5,6,7). Extension of the inflammatory process into the adjacent parenchyma results in 4 to 10 mm diameter centrilobular airspace nodules. These small foci of disease may progress to lobular, subsegmental, or segmental areas of consolidation characteristic of bronchopneumonia (see Fig. 5.5) (1,5,6,7). Partial filling of the airspaces results in ground-glass opacities (Fig. 5.5).

While some organisms, such as RSV and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, typically cause bronchiolitis, others, such as influenza virus may result in rapidly progressive pneumonia, particularly in the elderly and in immunocompromised patients (5). Histologically, the lungs in these patients show diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), characterized by interstitial lymphocyte infiltration, airspace hemorrhage and edema, type II cell hyperplasia, and hyaline membrane formation (5,8). The radiologic findings include homogeneous or patchy unilateral or bilateral airspace consolidation and ground-glass opacities (1,9,10).

Viruses

RNA Viruses

Influenza Virus

Influenza can occur as pandemics or epidemics, or sporadically in individuals or small clusters of patients. It has been estimated that influenza results in symptomatic

disease in approximately 20% of children and 5% of adults each year (11). The most common symptoms are sudden onset of fever, headache, myalgia, cough, and sore throat (12). Pneumonia is an uncommon but potentially severe complication of influenza infection. Although it may be caused by the virus itself (usually type A and occasionally type B organisms) (13,14) superimposed bacterial infection, particularly by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza, is more common (15).

disease in approximately 20% of children and 5% of adults each year (11). The most common symptoms are sudden onset of fever, headache, myalgia, cough, and sore throat (12). Pneumonia is an uncommon but potentially severe complication of influenza infection. Although it may be caused by the virus itself (usually type A and occasionally type B organisms) (13,14) superimposed bacterial infection, particularly by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza, is more common (15).

Primary influenza viral pneumonia occurs most commonly in the elderly and in patients with cardiopulmonary disease (15). The clinical manifestations in these patients typically include high fever, tachypnea, and

cyanosis developing within 1 day of the onset of influenza illness (15). Mortality in patients with primary influenza pneumonia is high (15). Pneumonia due to superimposed bacterial infection also occurs most commonly in the elderly and in patients with underlying pulmonary disease (15). Clinically, these patients initially present with typical influenza symptoms. The symptoms appear to be improving when the clinical course is complicated by recrudescence of fever and development of chills, pleuritic chest pain, and productive cough (15). The clinical symptoms in these patients tend to be milder than symptoms in those with primary influenza pneumonia and the mortality is lower (15). In one review of the clinical findings and complications in 35 patients hospitalized with influenza (10), approximately 90% of patients had serious comorbid illnesses, most commonly chronic respiratory or heart disease or diabetes. Seventeen patients developed pneumonia; these patients tended to be older (mean age 63 years) and had a higher incidence of chronic lung disease than those without pneumonia. Shortness of breath was the only symptom that distinguished patients with pneumonia from those with an upper respiratory tract illness alone. Respiratory test results and/or blood culture results were positive in five patients (29%); S. aureus was isolated in all five patients and S. pneumoniae in one patient. Ten of the patients with pneumonia (59%) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and five patients (29%) died (10).

cyanosis developing within 1 day of the onset of influenza illness (15). Mortality in patients with primary influenza pneumonia is high (15). Pneumonia due to superimposed bacterial infection also occurs most commonly in the elderly and in patients with underlying pulmonary disease (15). Clinically, these patients initially present with typical influenza symptoms. The symptoms appear to be improving when the clinical course is complicated by recrudescence of fever and development of chills, pleuritic chest pain, and productive cough (15). The clinical symptoms in these patients tend to be milder than symptoms in those with primary influenza pneumonia and the mortality is lower (15). In one review of the clinical findings and complications in 35 patients hospitalized with influenza (10), approximately 90% of patients had serious comorbid illnesses, most commonly chronic respiratory or heart disease or diabetes. Seventeen patients developed pneumonia; these patients tended to be older (mean age 63 years) and had a higher incidence of chronic lung disease than those without pneumonia. Shortness of breath was the only symptom that distinguished patients with pneumonia from those with an upper respiratory tract illness alone. Respiratory test results and/or blood culture results were positive in five patients (29%); S. aureus was isolated in all five patients and S. pneumoniae in one patient. Ten of the patients with pneumonia (59%) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and five patients (29%) died (10).

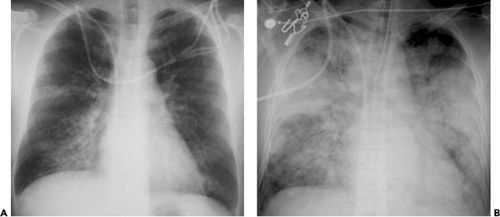

The most common radiographic manifestations of influenza pneumonia include extensive bilateral reticular or reticulonodular opacities with or without superimposed areas of consolidation (see Fig. 5.6 and Table 5.1) (1,10,15). Less commonly, patients with primary influenza pneumonia may present with focal areas of consolidation, usually in the lower lobes, without apparent reticular or reticulonodular opacities (see Fig. 5.7) (10,15,16). Serial radiographs may show poorly defined, patchy or nodular areas of consolidation, 1 to 2 cm in diameter, which become rapidly confluent (1,16). Pleural effusion is uncommon. The radiologic abnormalities usually resolve in approximately 3 weeks (16).

Kim et al. evaluated the high-resolution CT scan findings of influenza virus pneumonia in two immunocompetent patients and reported that both lungs had areas of multifocal peribronchovascular or subpleural consolidation (1). In one patient, some of the areas of consolidation had

a lobular distribution and were associated with airspace nodules. The other patient showed diffuse ground-glass opacities with irregular linear areas of increased attenuation. Tanaka et al. reported the high-resolution CT scan findings of influenza virus pneumonia in one immunocompetent patient as consisting of bilateral ground-glass opacities in a lobular distribution (17).

a lobular distribution and were associated with airspace nodules. The other patient showed diffuse ground-glass opacities with irregular linear areas of increased attenuation. Tanaka et al. reported the high-resolution CT scan findings of influenza virus pneumonia in one immunocompetent patient as consisting of bilateral ground-glass opacities in a lobular distribution (17).

TABLE 5.1 Influenza Virus | |

|---|---|

|

The manifestations of secondary bacterial pneumonia are those of bronchopneumonia and include lobular, subsegmental, or segmental unilateral or bilateral areas of consolidation (10,15,16).

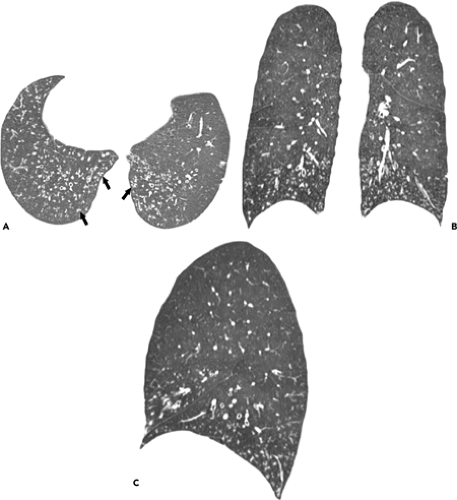

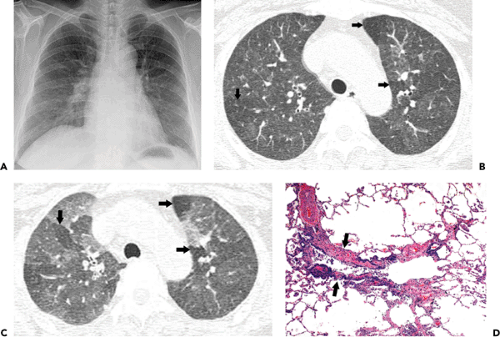

Influenza infection in the immunocompromised host usually presents with similar clinical findings as in the normal host. However, there is a greater prevalence of severe disease particularly in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (15,18). Oikonomou et al. described the radiographic and high-resolution CT scan findings of influenza pneumonia in four immunocompromised patients with hematologic malignancies (9). The most common finding on the chest radiographs was the presence of patchy, poorly defined areas of consolidation. The consolidation was bilateral in three patients and unilateral in one. Two patients had ill-defined small nodules and patchy ground-glass opacities evident on the radiograph. The findings on high-resolution CT scan included patchy ground-glass opacities, focal areas of consolidation, centrilobular nodules, and a tree-in-bud pattern (see Fig. 5.8). The centrilobular nodules measured 2 to 9 mm in diameter and were bilateral and asymmetric in distribution. The tree-in-bud pattern was limited to small areas of the parenchyma and was asymmetric and bilateral in distribution. The extent of abnormalities seen on high-resolution CT scan was greater than that apparent on the radiograph (9).

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

RSV is a common cause of upper and lower respiratory tract infection in infants and small children (16). Infection in adults is usually mild and limited to the upper respiratory tract; however, pneumonia can occur, particularly, in the elderly or chronically ill patients in nursing homes or hospital (19,20,21) and in immunocompromised individuals (22,23).

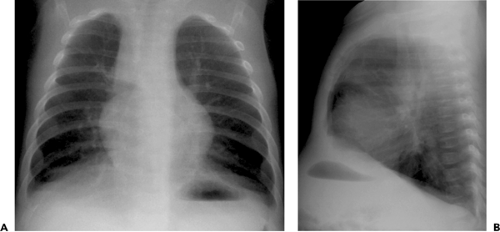

The radiographic findings in infants and children include bronchial wall thickening, peribronchial opacities,

and perihilar linearity (see Table 5.2) (16,24). Other common findings include hyperinflation (reflecting the presence of acute bronchiolitis) and patchy bilateral consolidation (reflecting the presence of bronchopneumonia) (see Fig. 5.9) (16,24). In one review of the radiographic manifestations of RSV lower respiratory tract infection in 108 children in the 1 day to 10 years age-group, the main findings included normal chest radiograph (30%), central consolidation (32%), or peribronchial thickening (26%) (25). Other findings included hyperinflation (11%), lobar consolidation (6%), patchy segmental consolidation (6%), and pleural effusion (6%).

and perihilar linearity (see Table 5.2) (16,24). Other common findings include hyperinflation (reflecting the presence of acute bronchiolitis) and patchy bilateral consolidation (reflecting the presence of bronchopneumonia) (see Fig. 5.9) (16,24). In one review of the radiographic manifestations of RSV lower respiratory tract infection in 108 children in the 1 day to 10 years age-group, the main findings included normal chest radiograph (30%), central consolidation (32%), or peribronchial thickening (26%) (25). Other findings included hyperinflation (11%), lobar consolidation (6%), patchy segmental consolidation (6%), and pleural effusion (6%).

TABLE 5.2 Respiratory Syncytial Virus | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The radiographic findings of RSV pneumonia in adults usually consist of patchy bilateral areas of consolidation (26). Less commonly, the patients may present with a bilateral reticulonodular pattern (26). The main high-resolution CT scan findings are centrilobular nodules and branching nodular opacities (tree-in-bud pattern), reflecting the presence of bronchiolitis, and multifocal ground-glass opacities or areas of consolidation, due to bronchopneumonia. Expiratory CT scan may show air trapping (see Fig. 5.10). In one review of 20 patients who had RSV pneumonia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, the predominant high-resolution CT scan findings included small centrilobular nodules (10 of 20, 50%), multifocal areas of airspace consolidation and multifocal ground-glass opacities (6 of 20, 30%), and bronchial wall thickening (6 of 20, 30%) (see Fig. 5.11) (27). The centrilobular nodules were 1 to 5 mm in diameter and in half the cases were associated with branching nodular and linear opacities resulting in a tree-in-bud pattern. The abnormalities were bilateral and asymmetric in distribution in 13 patients, bilateral and symmetric in 2 patients, and unilateral in 1 patient (27). In a review of the high-resolution CT scan findings in ten patients with RSV infection after lung transplantation (28), the main abnormalities included ground-glass opacities seen in seven of ten patients, airspace consolidation in five, and centrilobular nodular and branching linear opacities (tree-in-bud pattern) in four patients (28).

Hantaviruses

Hantaviruses are a group of viruses that cause two characteristic symptom complexes: Hemorrhagic fever with

renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is characterized by fever, hypotension, and renal failure (29,30). Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is characterized by the presence of respiratory distress from noncardiogenic edema (1). The most common organism responsible for the hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in North America is the Sin Nombre virus (31).

renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is characterized by fever, hypotension, and renal failure (29,30). Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is characterized by the presence of respiratory distress from noncardiogenic edema (1). The most common organism responsible for the hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in North America is the Sin Nombre virus (31).

The natural reservoirs of the Hantaviruses are wild rodents and deer mice (29,32). The organism is believed to be transmitted to humans by inhalation of dried rodent excreta associated with outdoor activities in rural areas, such as cleaning barns and harvesting rice. Increased contact between humans and rodent reservoirs has resulted in an increase prevalence of Hantavirus infections in the last two decades (32). A number of cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome have been described in North and South America and in Asia (31,32).

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome develops 9 to 35 days after exposure to the virus. It is characterized by three stages. The initial stage is the prodromal phase, which is followed by the cardiopulmonary and convalescent phases. The prodromal phase is manifested by a flu-like illness with myalgia, fever, headache, cough, vomiting, and diarrhea (30). This is followed within 3 to 6 days by progressive shortness of breath, progressive respiratory insufficiency, respiratory failure, and shock (30). Histologically, the cardiopulmonary phase is characterized by interstitial and airspace edema, mild to moderate interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, and epithelial necrosis with destruction of type I cells and hyaline membranes (1,33).

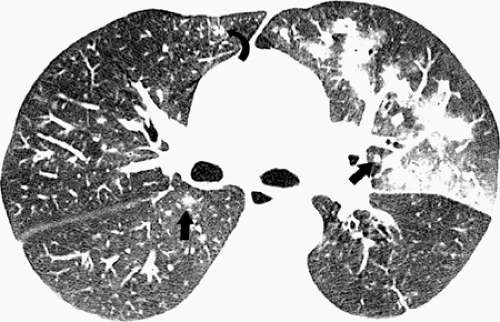

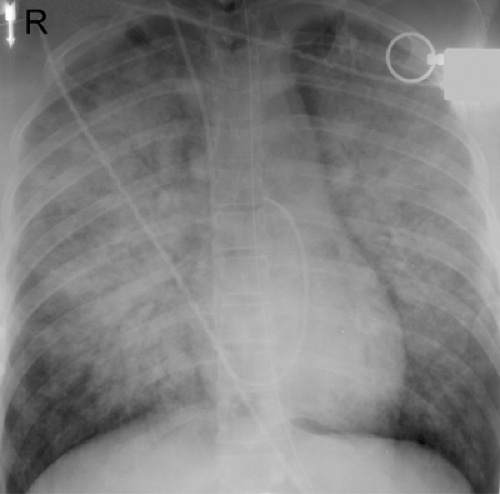

The radiographic manifestations include interstitial edema with or without rapid progression to airspace disease (see Table 5.3) (1,30,34). The airspace disease shows a central or bibasilar distribution (see Fig. 5.12). In most patients the radiologic manifestations of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome are consistent with those of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. However, renal failure may result in findings of interstitial and airspace hydrostatic pulmonary edema and cardiomegaly (see Fig. 5.13) (1).

Ketai et al. described the radiographic manifestations in 16 patients seen during an epidemic in the southwestern United States in 1993 (33). In 13 of the 16 patients, the initial chest radiographs showed findings consistent with those of interstitial pulmonary edema, including septal (Kerley B) lines, hilar indistinctness, and peribronchial

cuffing. In the three patients who had normal radiographs at presentation, findings consistent with interstitial pulmonary edema developed within 48 hours. Within 48 hours of admission, 11 patients developed extensive airspace consolidation. The distribution was bibasilar or perihilar in ten patients and predominantly peripheral in one patient. The time to resolution of the radiographic findings in the nine patients who survived ranged from 5 days to >3 weeks. Pleural effusions were present on the initial chest radiographs in two patients and developed within 48 hours in nine other patients. The effusions were small in five patients and large in six patients (33).

cuffing. In the three patients who had normal radiographs at presentation, findings consistent with interstitial pulmonary edema developed within 48 hours. Within 48 hours of admission, 11 patients developed extensive airspace consolidation. The distribution was bibasilar or perihilar in ten patients and predominantly peripheral in one patient. The time to resolution of the radiographic findings in the nine patients who survived ranged from 5 days to >3 weeks. Pleural effusions were present on the initial chest radiographs in two patients and developed within 48 hours in nine other patients. The effusions were small in five patients and large in six patients (33).

Boroja et al. (34) described the radiographic findings in 20 patients and identified two different patterns of presentation. Thirteen (65%) patients presented with fulminant clinical and radiographic findings and required intensive care support. The radiographic findings in these patients included interstitial edema with rapid progression to bilateral airspace consolidation. Six (46%) of these 13 patients died within a few days of presentation. The second group (7 of 20, 35%) presented with mild clinical symptoms. The radiographic findings included mild interstitial edema and minimal airspace consolidation that resolved in a mean time of 8 days. None of the patients in the second group died. Seventy-five percent (15 of 20) of the patients had small bilateral pleural effusions. One patient had a small right-sided pleural effusion, and three patients had no pleural effusion. Nineteen of the 20 patients (95%) lived or worked in rural communities or had contact with deer mice or deer mice droppings (34).

TABLE 5.3 Hantavirus | |

|---|---|

|

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus is the cause of SARS, which is a new infectious disease that first emerged in the Guangdong province in southern China, in November 2002 (35,36). SARS rapidly spread from China to affect patients in a number of countries around the world. Within approximately 8 months, the global cumulative total of the cases was 8,422 with 916 deaths (case fatality rate of 11%) (35).

The natural reservoir of the organism is believed to be wild animals such as raccoon-dogs, ferrets, and civets (36). The disease is transmitted by droplets or direct inoculation

from contact with infected surfaces (35). The mean incubation period was 6.4 days (range 2 to 10). The duration between onset of symptoms and hospitalization was 3 to 5 days (35). Presenting symptoms include fever, chills, dry cough, myalgia, and headache (37). These can progress to clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features of ARDS. Laboratory findings include lymphopenia, evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and elevated blood levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (37).

from contact with infected surfaces (35). The mean incubation period was 6.4 days (range 2 to 10). The duration between onset of symptoms and hospitalization was 3 to 5 days (35). Presenting symptoms include fever, chills, dry cough, myalgia, and headache (37). These can progress to clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features of ARDS. Laboratory findings include lymphopenia, evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and elevated blood levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (37).

Histologic assessment of autopsy specimens showed that the predominant pattern of lung injury was DAD. The histology varied according to the duration of illness. Cases of 10 or fewer days’ duration demonstrated acute-phase DAD. Cases of >10 days’ duration exhibited organizing-phase DAD, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, and, frequently, superimposed bacterial bronchopneumonia (38).

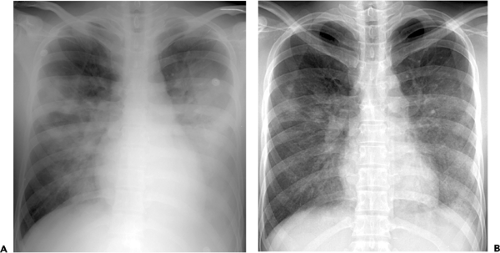

The most common radiologic manifestations include focal unilateral or multifocal unilateral or bilateral areas of consolidation (see Figs. 5.14 and 5.15 and Table 5.4) (39,40,41). The consolidation tends to involve predominantly the peripheral lung regions and the middle and lower lung zones (39,40,41). Less common radiographic findings include focal or diffuse ground-glass opacities and, rarely, lobar consolidation (see Fig. 5.16) (39,40,41). The extent of parenchymal abnormalities on chest radiography correlates inversely with the oxygen saturation (r = -0.67, p <0.001) (42).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree