Abstract

This chapter summarizes the basic approach for evaluation and characterization of ventricular septal defects (VSD) in adults. A brief description of nomenclature and associated cardiac evaluation is included. Finally, a schematic for a systemic approach to VSD evaluation is provided.

Keywords

adult congenital heart disease, ventricular septal defects

Adult Presentation

Most commonly, VSDs are diagnosed in childhood. Often, large VSDs are diagnosed due to recurrent infections or evidence of over-circulation, while small VSDs often present with loud murmurs. If small VSDs are diagnosed in adulthood, they can present with a murmur, the development of endocarditis, or valve damage related to the flow through the VSD. Large unrepaired VSDs can present in adulthood with evidence of pulmonary hypertension and reversal of the shunt (Eisenmenger syndrome). Additionally, increases in left ventricle (LV) systolic and diastolic pressures with aging can increase the degree of left-to-right (L–R) shunting. Common associated findings at the time of presentation include double-chambered right ventricle, subaortic stenosis, aortic prolapse, and arrhythmias. Additionally, adults can develop VSDs as a result of large myocardial infarctions (see Chapter 19 ). When evaluating VSDs by echocardiography, evaluation of ventricular size and function, valve function, estimate of pulmonary pressures, and exclusion of associated defects must be performed.

Types/Locations of Ventricular Septal Defects

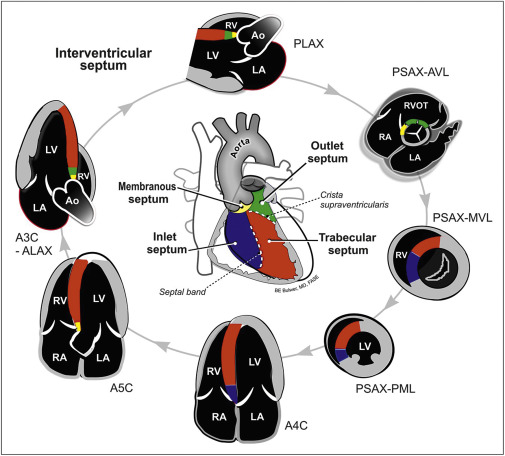

Based on the embryologic origins of the ventricular septum, VSDs can be categorized based on their location and structure, as shown in Fig. 44.1 .

Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defects

Defects of the membranous septum are the second most common type of defect in childhood but represent a larger portion of defects in adulthood as they are much less likely to spontaneously close. Membranous VSDs often occur in the setting of other types of congenital heart disease. They are often detectable in the parasternal long axis but may require slightly off-axis imaging to visualize the entire jet ( Fig. 44.2 and ![]() ). Based on their size and extension (VSDs may extend into the inlet, trabecular, or outlet septum), they can be associated with either aortic or tricuspid valve dysfunction, which is typically related to leaflet prolapse and regurgitation (

). Based on their size and extension (VSDs may extend into the inlet, trabecular, or outlet septum), they can be associated with either aortic or tricuspid valve dysfunction, which is typically related to leaflet prolapse and regurgitation ( ![]() ). If the defect is more significantly associated with the right ventricular outflow tract with anterior malalignment of the infundibular septum, it is called a conoventricular defect and is seen in tetralogy of Fallot. Thus, careful evaluation of valve function should be included in the echocardiographic exam of a VSD. Other imaging views to evaluate membranous VSDs include the parasternal short axis at the aortic valve level and the apical five-chamber view.

). If the defect is more significantly associated with the right ventricular outflow tract with anterior malalignment of the infundibular septum, it is called a conoventricular defect and is seen in tetralogy of Fallot. Thus, careful evaluation of valve function should be included in the echocardiographic exam of a VSD. Other imaging views to evaluate membranous VSDs include the parasternal short axis at the aortic valve level and the apical five-chamber view.

Muscular/Trabecular Ventricular Septal Defects

VSDs occurring solely in the muscular/trabecular septum constitute up to 20% of all VSDs. These can spontaneously close in infancy/childhood, but if persistently patent they can be closed percutaneously. Evaluation should include further characterization of location within the muscular septum (anterior, mid, apical, or posterior) as well as a meticulous search for multiple defects. At times, small jets of flow within the trabecula will occur that are not complete defects (i.e., no true shunt). Demonstration of flow through the septum is imperative and may require off-axis imaging or sweeping loop ( Fig. 44.3 and ![]() ). When imaging these defects, it is important to inspect each portion of the ventricular septum with a narrow color Doppler box to prevent missing small defects with bidirectional shunting. Screening for muscular VSDs can be done in the apical four-chamber view as well as the short-axis view at each level (vs. sweeping loops through the septum at each view).

). When imaging these defects, it is important to inspect each portion of the ventricular septum with a narrow color Doppler box to prevent missing small defects with bidirectional shunting. Screening for muscular VSDs can be done in the apical four-chamber view as well as the short-axis view at each level (vs. sweeping loops through the septum at each view).

Outlet Ventricular Septal Defects

The pulmonary artery connects to the heart via a ring of muscle (conus) that partially forms the outlet portion of the ventricular septum, which extends to the membranous septum. Due to the location, several different names for these defects have been given, including subpulmonic, doubly committed subarterial, conal, and supracristal. Slight changes in the location of the VSD in relationship to the great arteries can change the physiology of the defect. For example, if the defect is predominantly associated with the aorta, prolapse of the aortic valve can occur resulting in regurgitation and progressive valvular damage. Aortic valve damage can occur with both outlet and membranous defects. Outlet VSDs can be seen on the parasternal long axis when angled towards the outflow tracts, and in the short-axis view with the color Doppler sector focused on the conal septum ( Fig. 44.4 ).

Inlet Ventricular Septal Defects

Inlet defects occur as a result of deficiency in the ventricular septum between the inlet/atrioventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid), also called atrioventricular canal VSD. These defects can be diagnosed on transthoracic imaging at the level of the inlet valves, typically in the apical four-chamber view. Inlet VSDs constitute approximately 5% of all VSDs. The majority of the time they are associated with other defects with similar embryologic origin (endocardial cushion), such as cleft mitral valve, cleft tricuspid valve, and primum atrial septal defect (ASD). Collectively, this pattern is called an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) or endocardial cushion defect (shown in Fig. 44.5 ).