Chapter 8

Venous Thromboembolic Disease

Harjeet Rayt and Akhtar Nasim

Department of Vascular & Endovascular Surgery, Leicester Royal Infirmary, UK

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the formation of a thrombus in a vein, which may dislodge from its original site and travel to a distant site (embolism). The commonest site for the formation of thrombus is the deep veins of the leg, hence the name deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The embolus may travel to the lungs and lodge in the pulmonary vasculature causing a pulmonary embolus (PE). It has been estimated that approximately 25 000 people in the United Kingdom die per annum from preventable hospital-acquired VTE. This has been highlighted by a recent UK study that suggested that 71% of the patients with medium or high risk of developing DVT did not receive any form of thromboprophylaxis. Non-fatal VTE is also important as it causes long-term morbidity such as post-phlebitic syndrome.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Typically, a DVT starts in the calf veins and presents with pain, swelling and erythema (Figure 8.1). Tenderness may be found in the thigh or calf, there may be unilateral pitting oedema and the patient may exhibit mild pyrexia. However, the symptoms of DVT can be vague and other differential diagnoses must also be considered (Box 1). The risk factors for DVT are listed in Table 8.1. Lower limb DVT can be subdivided into distal (calf) or proximal (thigh), with the greatest risk of PE arising from a proximal DVT.

Table 8.1 Risk factors for venous thromboembolism.

| Acquired disorders | Inherited/congenital disorders |

| Malignancy | Antithrombin deficiency |

| Surgery, especially orthopaedic | Protein C deficiency |

| Presence of central venous catheter | Protein S deficiency |

| Trauma | Factor V Leiden mutation |

| Pregnancy, HRT, oral contraceptive | Prothrombin gene mutation |

| Prolonged immobilisation | Dysfibrinogenaemias |

| Dehydration | Factor VII deficiency |

| Age over 60 | Factor XII deficiency |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | |

| Previous VTE | |

| Congestive cardiac/respiratory failure | |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | |

| Myeloproliferative disorders | |

| Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus | |

| Hyperviscosity syndromes (myeloma) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Acute medical illness | |

| Behcet’s disease | |

| Varicose veins with associated phlebitis |

Figure 8.1 Photo of a patient with a left leg deep vein thrombosis.

Pathophysiology

Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902) described a triad of factors that were broadly responsible for the formation of thrombosis. These are slowing in blood flow (stasis), changes in blood components (hypercoagulability) and damage to the vessel wall (venous injury). These factors are still responsible for DVT in modern practice. Stasis could be caused by immobility of the patient; hypercoagulability could be due to dehydration or effects of impaired coagulation and venous injury could be due to iatrogenic trauma or from the effects of inflammatory cytokines.

The thrombus usually forms close to the vein wall, usually in a valve pocket. This is rich in red blood cells and described as a red thrombus. As the thrombus propagates towards the lumen, more platelets and fibrin are involved and lead to a white appearance of the clot. From here, the clot either occludes the vein locally or forms a free-floating non-occlusive clot that can dislodge to a distant site.

Diagnosing DVT

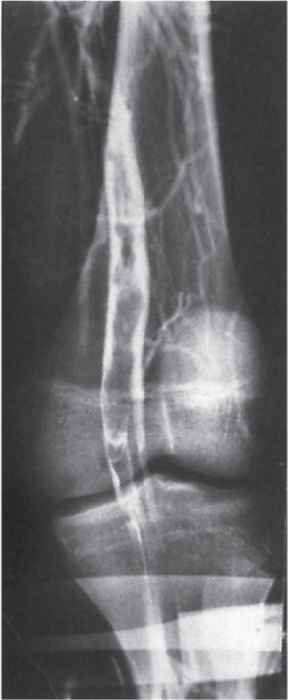

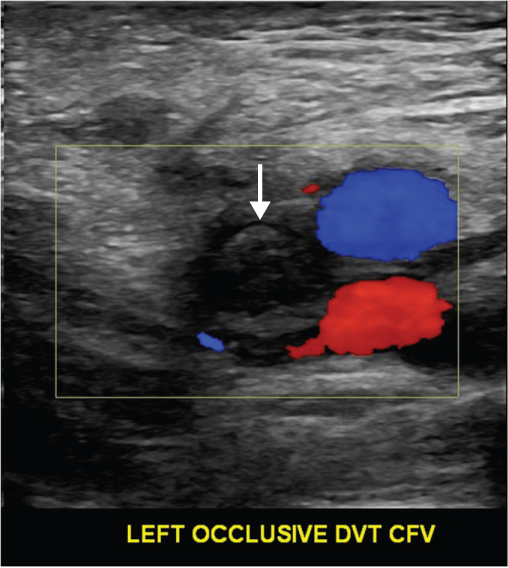

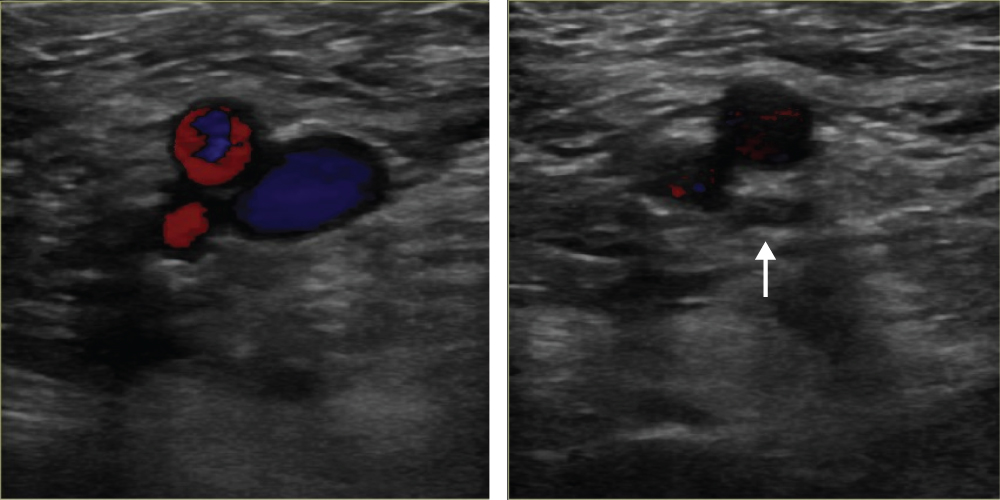

Clinical diagnosis of DVT is unreliable and uses outdated historical tests such as Homan’s sign. The most important serum investigation is a D-dimer test. The D-dimer examination has a high negative predictive value and can therefore be used to exclude a diagnosis of DVT if not elevated. However, an elevated value is non-specific and can occur in malignancy, pregnancy, recent surgery or trauma. Venography is the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic tool for DVT; however, its use is limited as the test can be painful and uses contrast medium (nephrotoxicity and anaphylaxis) (Figure 8.2). Venous ultrasonography is currently the investigation of choice. It is non-invasive, inexpensive, painless and readily accessible (Figure 8.3). It has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 97% for the diagnosis of proximal DVT. A compression technique is used whereby the veins of a healthy vein can be opposed, whereas the walls of a vein containing thrombus remain apart (Figure 8.4). Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and impedance plethysmography may also be used.

Figure 8.2 A venogram showing extensive thrombus (filling defect) in the popliteal vein.

Figure 8.3 Duplex ultrasound scan demonstrating lack of flow in the common femoral vein indicating an occlusive DVT (arrow).

Figure 8.4 Normal duplex ultrasound scan demonstrating compression of the vein (arrow).

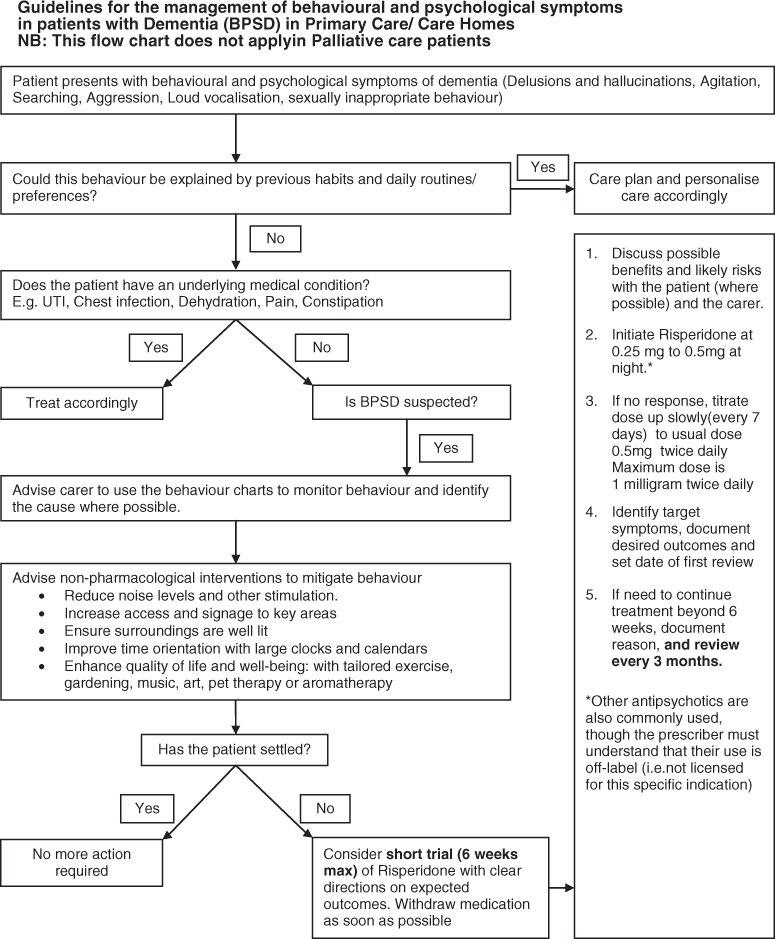

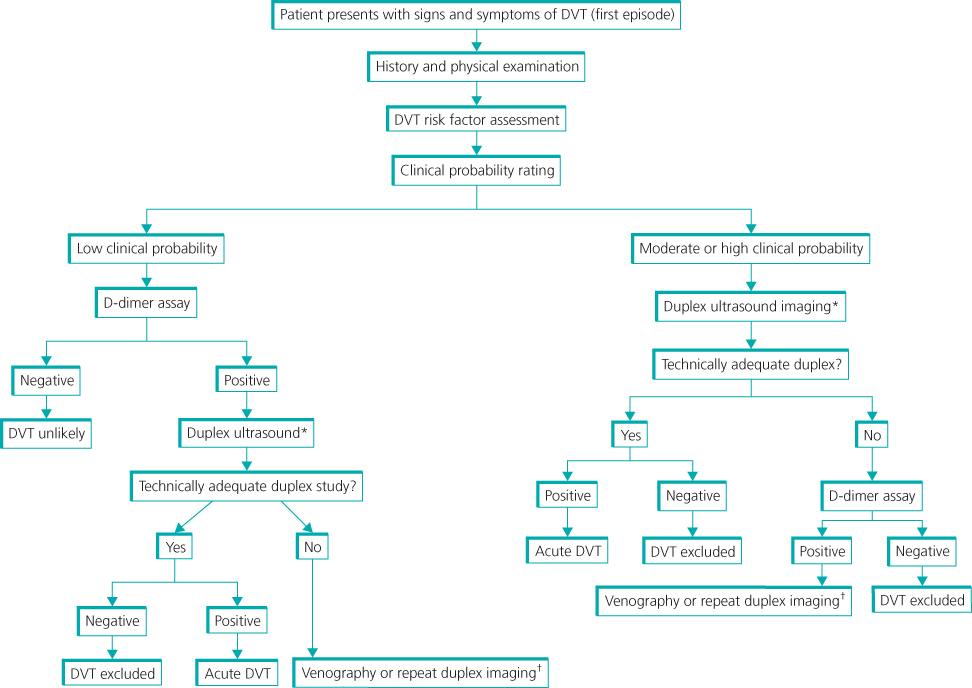

To avoid unnecessary investigation, several clinical prediction tools have been devised that incorporate symptoms, signs and risk factors to stratify patients into low or high risk for DVT (Table 8.2). This has been used along with D-dimer testing and ultrasonography to develop a diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected DVT (Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 Algorithm for diagnosis of DVT. *, Duplex ultrasound includes complete evaluation of the lower extremity, including compression, Doppler waveforms, and colour Doppler of the calf veins and iliac veins. †, Contrast venography or magnetic resonance venography are warranted if the initial duplex study is technically inadequate or non-diagnostic. Source: Zierler (2006). Reproduced by permission of Wolters Kluwer Health.

Table 8.2 Clinical model for predicting pretest probability of DVT (Wells’ score).

| Clinical characteristics | Score |

| Active malignancy (ongoing treatment or palliative) | 1 |

| Immobilisation by paralysis or plaster dressings | 1 |

| Recently bedridden for >3 days or major surgery within previous 4 weeks | 1 |

| Localised tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system | 1 |

| Whole leg swollen (thigh and calf) | 1 |

| Calf swelling >3 cm compared to asymptomatic leg (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) | 1 |

| Pitting oedema (confined to symptomatic leg) | 1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (non-varicosed) | 1 |

| Previous documented DVT | 1 |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT | −2 |

Source: Zierler (2004). Reproduced by permission of Wolters Kluwer Health.

DVT likely if score ≥2, unlikely if score ≤1.

Low probability of DVT 0; high probability ≥3.

Complications of DVT

The main complications of DVT are pulmonary embolism (PE), venous insufficiency and recurrent thrombosis.

Pulmonary embolism

PE is a serious complication of DVT, with a reported 30-day mortality rate of approximately 10%. A massive PE results from a large embolus that obstructs the main pulmonary artery, leads to acute right ventricular failure and can be fatal. Smaller emboli lodge more distally in the pulmonary arterial tree and cause cardiorespiratory symptoms (Box 2). Diagnosing PE always requires a high index of suspicion as some may present with very little symptoms. Most PE are multiple and commonly affect the lower lobes. The ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis is a pulmonary angiogram. This is an expensive, invasive test that requires trained radiologists and co-operative patients and has therefore largely been reserved for patients in whom non-invasive tests are inconclusive. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) has now taken over as the investigation of choice for diagnosing PE. This is a non-invasive, fast, widely available test that allows visualisation of the entire lung fields as well as the pulmonary tree (Figure 8.6). Alternative diagnoses can therefore be determined. However, problems with the above-mentioned investigations are high radiation exposures, which can be problematic in pregnancy and contrast media and may cause nephrotoxicity or anaphylaxis. In these circumstances, a ventilation/perfusion scan is a safer alternative. Treatment for PE centres around anticoagulation and supportive cardiorespiratory measures. Massive PE resulting in haemodynamic compromise (hypoxia, tachycardia and hypotension) is an indication for thrombolysis. Surgical management of massive PE is no longer recommended.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree