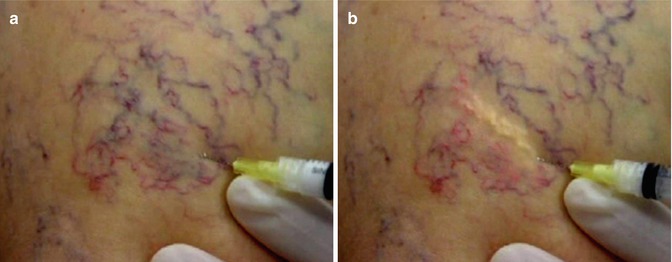

Fig. 20.1

Telangiectasia in the medial aspect of leg and thigh

It is important to rule out other causes of primary and secondary telangiectasias. This is relevant especially if laser treatment is planned, since some of these conditions can be aggravated by laser application [6].

Prior to treatment, a duplex venous scan to rule out reflux in the saphenous, perforator, and deep venous system is necessary. There is general agreement that such pathologies should first be corrected before planning treatment for the smaller veins [6, 10]. The treatment outcome would be unsatisfactory in the presence of a persistent saphenous reflux [10]. No specific imaging modalities are recommended for the small veins. High-resolution US and LDPI are mentioned in some reports [3, 12].

Treatment of Telangiectasia and Reticular Veins

Certain basic issues should be understood by the patient and physician before proceeding with treatment of these conditions.

C1 disease seldom poses any threat to the life of the patient and does not usually progress to C2 stage [10].

The commonest indication for treatment is cosmetic. In this setting, there can be a huge gap between the expectation of the patient and the actual outcome of treatment.

When treatment is offered to relieve the symptom of throbbing and pain in the lower limb, it is important to rule out musculoskeletal and other causes for such pain.

Treatment Options

Treatment of C1 disease is a challenge. Surgery has no place since the veins involved are very small. Therapeutic options include sclerotherapy, transcutaneous laser/intense pulsed light (IPL), and cosmetic camouflage, if no interventions are possible [2].

Sclerotherapy for Reticular Veins and Telangiectasia

This is a simple and effective method of treatment of small veins. At present, it is considered to be the gold standard in the treatment of telangiectasia and reticular veins. For vessels less than 1 mm, only liquid sclerosants are recommended in strength of 0.1–0.2 % [4]. Foam sclerosants can be used for vessels of size between 1 and 3 mm. Both sodium tetradecyl sulfate and polidocanol are used in concentrations from 0.1 to 0.5 %.

The injection of sclerosant is by the direct cannulation technique. One milliliter syringes fitted with 30-gauge needle is used for cannulation. Good lighting and a magnifying loupe (×2–3) are very helpful. It is always better to “test treat” a small area first, to assess the response and patient compliance [4].

For feeder reticular veins, the cannulation is done with the patient in the recumbent position. The technique of air block is useful in cannulating small veins. The tiny air bubble loaded into the syringe will produce immediate blanching of the vein if the needle is correctly placed [13]. At each site 0.25–0.5 ml of liquid sclerosant is injected [13]. Sometimes, the sclerosant can be seen to pass from the reticular vein into the telangiectasia; it is not necessary to inject the telangiectasia if this happens [4]. Soon after the needle is withdrawn, local pressure is applied by a pad and plaster. The total volume of the sclerosing agent is limited to 2–4 ml/sitting [13].

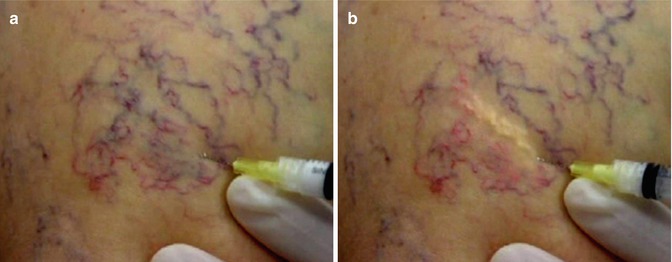

For telangiectasia the technique is almost the same. Here, only liquid sclerosants are used and the volume is only 0.1–0.2 ml/site. The injections are made at the point of convergence of the venules (Fig. 20.2a). This produces a blanching of 2 cm radius from this site [4] (Fig. 20.2b). The injection has to be performed very slowly.

Fig. 20.2

Sclerotherapy for telangiectasia. (a) cannulation of the telengiectasia, (b) injection in progress. Note the blanching effect

After injection, the area is massaged and compression pads are applied. Extravasation can produce skin necrosis and should be avoided. If there is resistance to injection or if a bleb appears, it is stopped immediately. Application of 2 % nitroglycerine cream can minimize necrosis by producing vasodilatation [4]. Thigh-length compression stocking is applied for 3–4 days. Patient is encouraged to walk and be active. Ideal treatment interval is between 4 and 8 weeks [4]. After the initial treatment, a gap of 4–6 months is recommended before a fresh course of treatment is planned. This is to settle the skin coloration [4].

The adverse events include skin necrosis/ulceration and insufficient sclerosis. Thrombosis of the vessels is not uncommon and is treated by needle aspiration and evacuation of the clot. The technique of decompressing thrombosed 1 mm veins is called “microthrombectomy” [13]. It is performed by multiple punctures with a 22-gauge needle or by mini incisions at multiple sites [13]. An uncommon event is “matting” – presence of a fine reddish network of small veins [13].

Transcutaneous Laser Treatment

Lasers and intense pulsed light (IPL) are not replacements for sclerotherapy in the treatment of telangiectasia. Sclerotherapy is a more effective method of eradicating cannulable vessels and is the gold standard in treatment. Indications for laser treatment are non-cannulable vessels, telangiectatic matting, sclero-resistance, and needle-phobic patients [6, 14]. The advantages claimed for laser treatment are many. It is a fast and simple noninvasive technique, requiring no wound dressings and posttreatment compression stocking. The treatment can be completed in one session since there is no maximum total dose unlike in sclerotherapy [6]. Laser treatment is contraindicated in tanned skin, pregnancy, use of iron supplements, photosensitivity, and patients prone for hypertrophic/keloid scarring [14].

Laser treatment works on the principle of selective photothermolysis [14]. This is based on two factors – selective absorption of light energy by the oxyhemoglobin in the leg vein and use of suitable pulse energies and pulse widths (pulse duration). The energy should correspond to the thermal relaxation time of the target. Thermal relaxation time indicates the time taken for transfer of heat, from the heated-up target tissue to the cooler surrounding tissues. To ensure optimum outcome, the following basic principles should be observed [14]:

Appropriate wavelength better absorbed by the hemoglobin than the surrounding tissues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree