9 Venous Anomalies

Background

• Isolated congenital anomalies of large systemic veins such as persistent left-sided superior vena cava (SVC) or interrupted inferior vena cava (IVC) have no hemodynamic impact and are usually found incidentally.

• Totally anomalous and partially anomalous pulmonary venous connections are two conditions in which one or more pulmonary vein (PV) segments do not connect directly to the left atrium (LA). Instead, the PV connects with a systemic vein, mixing with deoxygenated blood before returning to the right atrium (RA).

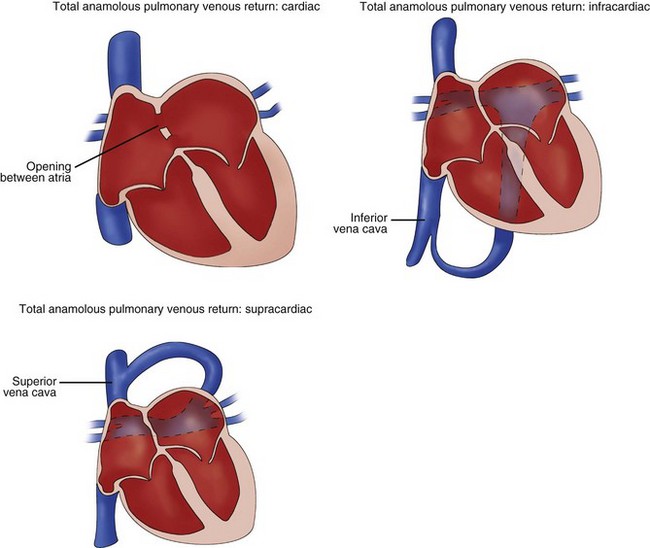

• The anomalous connections, whether total or partial, can occur at any level of systemic venous return: supracardiac such as the innominate veins, cardiac level such as the coronary sinus (CS), or infracardiac such as the IVC (Fig. 9-1).

• In normal anatomy, four separate PVs are the most common arrangement, although normal variations in this number also exist. An entire lung can join a single confluent vein before connecting to the LA. Likewise, each lobe of the right lung can have its own vein connect, leading to five total connections.

• In total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC), a right-to-left shunt, typically interatrial, is necessary to supply left ventricular preload.

Overview of Echocardiographic Approach

• Direct visualization of PV connections to the LA is typically easier for younger and smaller patients.

• All available transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) windows should be used to evaluate and demonstrate pulmonary or systemic venous connections, whether normal or abnormal. Optimal windows depend on which specific PV is being imaged (Table 9-1).

• Color Doppler maps are useful in confirming an individual systemic or PV connection. Low Nyquist settings, 50 cm/s or less, should be used to ensure adequate color signals. The use of higher settings may lead to a low-signal or even absent color map. PV flow is low velocity, and with some TTE windows, the angle of interrogation can be occasionally perpendicular to the vein.

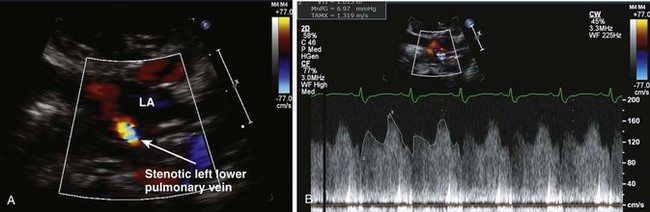

• For any patient with a history of anomalous PV surgical repairs, individual veins should be evaluated for stenosis (Box 9-1, Fig. 9-2).

TABLE 9-1 RECOMMENDED VIEWS TO EVALUATE PULMONARY VEIN ANATOMY

| View | Best-Viewed Pulmonary Veins |

|---|---|

| High parasternal short axis (crab view) | RLPV, LUPV, LLPVMore challenging: RUPV |

| Apical 4 chamber | RLPVMore challenging: Left lower pulmonary vein origin is adjacent to the left atrial appendage ostium |

| Apical 5 chamber / LVOT | RUPV, LLPV |

| Parasternal long axis | Left pulmonary veins (upper and lower can be difficult to distinguish) |

| Subcostal long axis | RUPV, RLPV, LUPV, LLPV |

| Subcostal short axis | RUPV |

Box 9-1

Postoperative Evaluation of Patients with Repaired TAPVC/PAPVC

Anatomic Imaging

Pulmonary Veins

• A high parasternal short axis (SAX) view, angled inferiorly toward the LA, creates the “crab” view (Fig. 9-3). In this plane, four PVs can be visualized at once. Care must be taken to ensure the left atrial appendage is not confused for the left upper PV (LUPV).

• Right parasternal and subcostal views can help confirm the presence of a normal right upper PV (RUPV) connection; the SVC serves as the anatomic landmark because the RUPV courses directly posterior to it (Fig. 9-4). Other, less commonly used windows can be applied to identify normal connections. For example, from the parasternal long axis (LAX) view, a left-sided PV connection can be detected by two-dimensional (2D) and color imaging (Fig. 9-5).

• Size discrepancy between the IVC and SVC can be a subtle sign of anomalous connections; the systemic vein receiving the PV connection will be dilated out of proportion to the remaining systemic veins.

• In scimitar syndrome, part or all of the right-sided PVs connect anomalously to the IVC. The PVs are oriented more vertically and become more dilated as they approach the heart, creating a curved swordlike (“scimitar”) appearance on a chest radiograph (Fig. 9-6).