Signs and Symptoms

RP is a historical diagnosis. The physical examination in primary RP is typically negative as almost all patients do not present at the time of the episode.

Table 18.1 lists the diagnostic criteria for primary RP. A useful historical clue in differentiating intermittent vasospasm (primary RP and early secondary RP) from spasm in conjunction with arterial obstruction (typical in severe secondary RP) is whether the symptoms are constant or intermittent. Constant, symptomatic ischemia evidenced by rest pain or ulceration is invariably caused by fixed obstruction that may occur with severe secondary forms of RP. Thus, findings of rest pain or ulcerations are not consistent with a diagnosis of primary RP.

Table 18.2 lists other features that are helpful in the differentiation of primary from secondary RP. Nail fold capillaroscopy should be performed in all patients with manifestations of RP with “scleroderma pattern” representing the most specific finding associated with connective tissue disease. It is typified by dilated capillaries,

hemorrhages, avascular areas, and neoangiogenesis and is found in about 90% of patients with clinically overt systemic sclerosis. Similar changes also occur in dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and overlap syndromes. The absence of abnormal capillaroscopic findings is one of the diagnostic criteria for primary RP.

Unilateral RP: The presence of unilateral features again should warrant a careful investigation for secondary, especially embolic, causes. The most common embolic sources are the proximal large upper extremity arteries that may be involved as part of atherosclerosis, vasculitis, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), and Buerger’s disease. Other potential causes of unilateral symptoms may originate distal to the wrist and include occupational and trauma-related conditions (see below under differential diagnosis).

Pathophysiology

The etiology of RP is not clearly understood. The etiology of vasospasm in both primary and secondary RP is complex and reflects the complex interaction of the endothelium, smooth muscle, and neural and circulating or paracrine mediators that may all play a role in the regulation of cutaneous vascular tone. The normal neural regulation of cutaneous blood flow in response to stimuli such as cold (as opposed to other areas of circulation) is through sympathetic adrenergic vasoconstrictor fibers via the postjunctional α2c receptors in the vascular smooth muscle cells. Vasodilation is partially through the withdrawal of the sympathetic stimulus. Elevations in vasoconstrictors such as endothelin-1, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), and thromboxane A2 have all been demonstrated in RP. In addition, diminished fibrinolytic and potentiation of prothrombotic factors have also been noted. These factors have been suggested to represent consequences of disordered nitric oxide generation or may play a primary etiologic or potentiating role in the genesis of the abnormal responses that are typical of RP. Genetic and hormonal factors may also play a role in influencing propensity as indicated by the familial aggregation of this disorder and its tendency to affect females in excess of males. Recently, five candidate regions have been mapped out; some of which may contain genes that may play a role in the inheritance of this condition.

Differential Diagnosis

RP is a historical diagnosis. This implies that it may need to be distinguished from other physiologic symptoms and signs that may be encountered on exposure to cold or conditions such as acrocyanosis that may mimic RP. Rarely, even acrocyanosis patients may develop superimposed episodes of Raynaud’s syndrome. A variety of neurologic conditions may result in nonspecific tingling or vasomotor symptoms and should be distinguished from true RP. To complicate matters, true RP may occur in 10% of patients with compressive neuropathies such as carpal tunnel syndrome (compression of the median nerve from etiologies such as localized tenosynovitis, trauma, hypothyroidism, amyloidosis, or activities associated with repetitive motion of the wrist). The diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome is entertained when tapping the volar surface of the wrist (Tinel’s sign) or maintaining flexion of the wrist (Phalen’s maneuver) elicits symptoms. Complex regional pain syndrome or CRPS [reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD)] should also be considered in the differential diagnosis (see below).

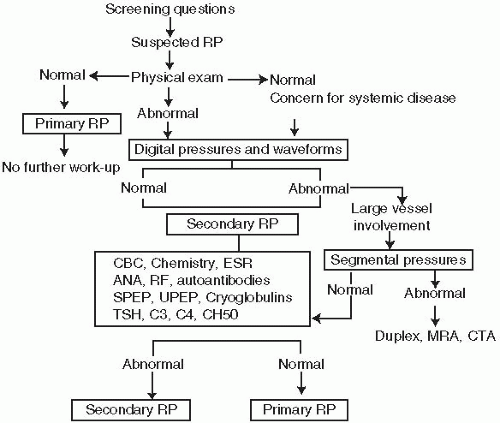

Once the diagnosis of RP is made, it is important to differentiate primary from secondary etiologies, as this has important prognostic and therapeutic ramifications. A complete list of causes of secondary RP is given in

Table 18.3.

Connective Tissue Diseases. Connective tissue diseases account for fewer than 20% of all patients with RP but account for the majority of patients with secondary forms of RP. These patients tend to have the most severe form of the disease. RP can occur with PSS or the CREST variant (more than 90% suffer from RP), MCTD (more than 80%), SLE (more than 30%), dermatomyositis (more than 25%), and rheumatoid arthritis (more than 10%).

Buerger’s Disease (Thromboangiitis Obliterans). Upper extremity involvement is frequently reported in Buerger’s disease, with 20 to 50% of these patients demonstrating secondary RP with evidence of obstructive lesions in the digits.

Mechanical Injury. Trauma-induced RP can occur with frostbite or crush injury and with traumatic aneurysms of the radial and ulnar arteries. A vascular steal syndrome following dialysis shunting may also cause a severe form of RP, which leads to severe distal ischemic injury. The “hypothenar hammer syndrome” occurs with repetitive injury to the ulnar artery (pounding or twisting) at the level of the hypothenar prominence that results in injury to the ulnar artery and/or the development of aneurysms. Patients typically present with RP confined to a few digits of the dominant hand (fourth and fifth digits) and an abnormal Allen’s test (owing to occlusion of the distal ulnar artery.

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. TOS is a rare cause of RP and most often results in vasomotor symptoms that can be confused historically for RP. True vascular TOS is extremely rare, and more often, compression of the neurovascular bundle in the neck and shoulder region may result in neurovascular symptoms that may be mistaken for RP. Unilateral presentations should raise the possibility of this disorder. Diagnostic difficulties may arise with primary RP and a cervical rib that may be an incidental finding. See

Chapters 16 and

17 for diagnosis and management of this disorder.

Arterial Disorders. RP may occur as a consequence of embolic phenomena from proximal large-vessel involvement due to atherosclerosis, aneurysmal disease, and vasculitis (Takayasu’s and giant cell arteritis). A high index of suspicion for embolic disease must be maintained, particularly in the setting of unilateral symptoms. Patients with atherosclerosis are generally older, unless they have severe dyslipidemias or long-standing tobacco use.

Toxins. Heavy metal poisoning (arsenic, mercury, and lead) and exposure to vinyl chloride may cause secondary RP. Exposure to vinyl chloride causes acroosteolysis-a disorder associated with resorption of the distal phalangeal tufts, a finding similar to that seen with PSS. Angiography reveals multiple arterial stenosis and occlusions along with hypervascularity adjacent to areas of bony resorption.

Rhéologic and Hematological Causes. Diseases that alter the macromolecular or cellular components of blood and increase blood viscosity may contribute to the development of RP. Polycythemia, thrombocythemia, and

chronic myeloid leukemia may all be associated with RP. Cryoglobulinemia, cryofibrinogenemia, cold agglutinins, and paraproteinemia may also present with RP but are rarer causes.

Drugs. The ergot derivative bromocriptine mesylate, used to treat Parkinson’s disease; drugs used to treat migraine headaches; and amphetamines are all reported to aggravate arterial vasospasm. RP may also occur with β blockers due to unopposed α-adrenergic vasoconstriction. Chemotherapeutic agents and interferon α/β may also precipitate RP.

Risk of Progression of Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Prognosis

In patients with RP and no associated symptoms and normal serology (normal ESR and normal ANA), the risk of an eventual diagnosis of a rheumatologic disorder is 2 to 3% over 5 years, while the risk of progression of symptoms is 6% over a 10-year period. The risk of an eventual rheumatologic disorder being diagnosed at the time of initial evaluation or in the future in the presence of RP and a positive ANA is high (above 50%). The 2-year risk of a rheumatologic disease in patients with RP and/or an abnormal nail fold examination and positive autoantibodies is 15 to 20%. The risk for development of secondary etiologies with an initial diagnosis of primary RP and borderline elevations in ANA titers remains unknown. A number of specific autoantibodies are much more helpful in predicting risk of eventual diagnosis of a rheumatologic disease. The most useful tests include anti-Smith (anti-Sm), which is predictive for development of SLE; Scl-70 (predicts PSS); and anticentromere antibodies (predicts CREST). The presence of antibodies to antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) (MCTD) is predictive of severe RP compared with those with other serologic markers.