Chapter 12

Vasculitis

Matthew D. Morgan1, Stuart W. Smith1 and Janson C.H. Leung2

1School of Immunity and Infection, College of Medical & Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK

2Department of Renal Medicine, Royal Derby Hospital, UK

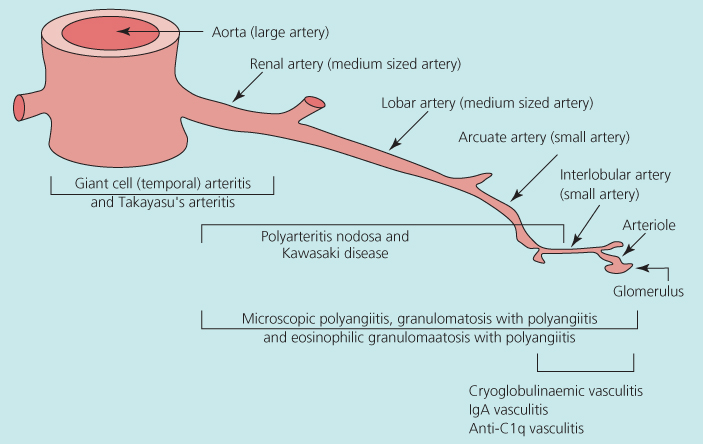

The vasculitides are a group of diseases causing inflammation in blood vessel walls. They are usually classified as primary or secondary (to diseases such as bacterial endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus or drugs such as propylthiouracil) and can be localised (affecting usually only the skin or a single organ system) or systemic (affecting multiple organ systems). This chapter focuses on the primary systemic vasculitides (PSVs). The PSVs are usually grouped together as large, medium or small vessel diseases according to the smallest size of vessel involved (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Spectrum of systemic vasculitides organised according to predominant size of vessels affected. Source: Adapted from Jennette et al. (2012). Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

The aetiopathogenesis is still not well understood for most PSVs, and so the classification of the diseases is not completely satisfactory. Most PSVs have classification criteria that were defined at the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC). These classification criteria are based on a combination of clinical features and pathological findings. The CHCC classification criteria will be used throughout this chapter.

The clinical features seen in PSVs can be divided into those features that are common to most systemic inflammatory diseases (fever, malaise, weight loss, night sweats, arthralgia and myalgia) and those features that are specific to the organ systems involved in the disease. Evidence of an acute phase response is common to most active PSVs, with a raised serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or plasma viscosity (PV).

Because the pathogenesis is still poorly understood, the mainstay of treatment for most PSVs is still immunosuppression with corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents. Many of the immunosuppressive regimes used in PSVs are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Many of the drug trials in recent years have been designed to investigate therapeutic regimes that reduce the immunosuppressive burden for patients while still maintaining disease control.

Large-vessel vasculitis

Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis)

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common form of PSV in the United Kingdom. It may affect any of the major branches of the aorta. Clinical features include unilateral throbbing headache, facial pain and claudication of the jaw when eating (Box 12.1). Visual loss is a feared complication of the disease, and it may be sudden and painless, affecting some or all of the visual field. Diplopia and other cranial nerve lesions may occur.

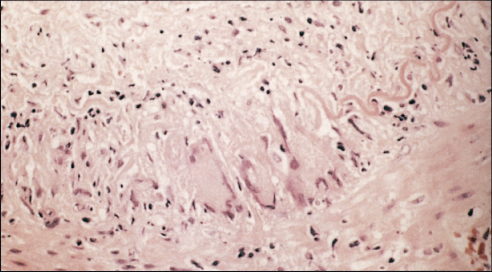

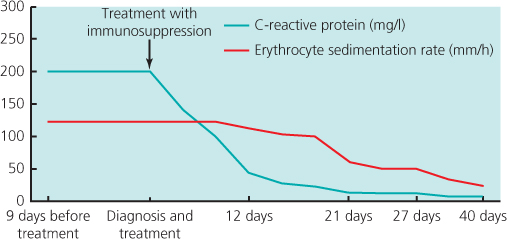

Initial treatment is with high-dose prednisolone (40–60 mg/day), which should be started as soon as the diagnosis is suspected to avoid visual loss. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy of the affected artery (Figure 12.2). The addition of methylprednisolone may improve remission rates and reduce corticosteroid exposure. Duplex sonography, high-resolution MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and positron emission tomography (PET) may be useful in the initial assessment of disease extent and monitoring of vascular inflammation. The corticosteroid dose may be reduced to 10 mg/day over 6 months and then more slowly to a maintenance of 5–10 mg/day. However, a sizable number of GCA patients flare upon tapering or withdrawing corticosteroid therapy. Maintenance treatment may be required for 2 years. From the result of meta-analysis of three randomised control trials, the addition of methotrexate to corticosteroids may reduce risk of first relapse by 35% and the risk of second relapse by 35%, as well as corticosteroid exposure. Etanercept may also allow a reduction of corticosteroid dose for patients with side effects, but the result from one trial was not statistically significant probably due to the small sample size. The reports of use of tocilizumab, a humanised anti-interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor antibody, are encouraging, and randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm its efficacy. Prevention of platelet aggregation with low-dose aspirin is potentially effective in preventing ischaemic complications of GCA. The disease is monitored by measuring acute phase response markers and sometimes using non-invasive imaging (Figure 12.3).

Figure 12.2 Temporal artery biopsy specimen with giant cell inflammation.

Figure 12.3 C-reactive protein concentration (>10 mg/l) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (>18 mm/h) are raised at time of diagnosis of giant cell arteritis but fall to normal levels after starting immunosuppression therapy.

Takayasu’s arteritis

Takayasu’s arteritis (Box 12.1) is most common in Asia, affects more women than men and is usually diagnosed in patients <50 years of age. Inflammation and then scarring of the aorta and its major branches leads to aortic arch syndrome with claudication of the arm, loss of pulses, variation of blood pressure of >10 mmHg between the arms, arterial bruits, angina, aortic valve regurgitation, syncope, stroke and visual disturbance. Involvement of the descending aorta may cause bowel ischaemia, mesenteric angina, renovascular hypertension, renal impairment and lower limb claudication. Diagnosis is by angiography, MRI or PET scanning. (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose PET ((18)F-FDG_PET) is a promising new imaging technique for early diagnosis and disease monitoring. Treatment of acute disease in patients with high CRP or ESR is with corticosteroids. Cytotoxic drugs such as cyclophosphamide can be added if steroids alone do not control the disease. Encouraging preliminary results have been obtained with tocilizumab. There are case reports of successful treatments with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, and leflunomide. Surgery or angioplasty may be required for stenoses once active inflammation has been controlled.

Medium vessel vasculitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) (Box 12.2) is rare in the United Kingdom. It is associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in some patients. Disease of medium-sized arteries leads to ischaemia or infarction within affected organs. The disease can involve the gut, causing abdominal pain, bleeding or perforation; in the heart, it can cause angina or myocardial infarction; cortical infarcts and ischaemia in the kidneys can lead to renal impairment and hypertension and involvement of the peripheral nervous system can cause mononeuritis multiplex.

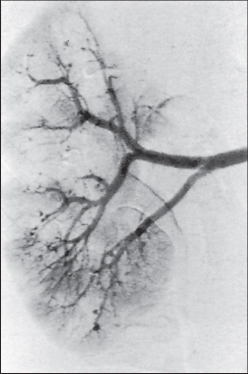

Diagnosis is based on the demonstration of arterial aneurysms in the renal, splanchnic, hepatic or splenic vessels using angiography (Figure 12.4). Biopsy of affected muscles or nerves may reveal histological evidence of arteritis.

Figure 12.4 Renal angiogram showing multiple arterial aneurysms.

Treatment of PAN associated with HBV requires an antiviral drug such as interferon α or lamivudine combined with short-course, high-dose corticosteroids and plasma exchange. For non-HBV-associated PAN, the severity of disease at presentation predicts the long-term outcome, with worse survival seen in those patients having more severe disease. The addition of 12 pulses of intravenous cyclophosphamide over 10 months to corticosteroids may improve outcomes for patients with severe disease.

Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki disease (KD) (Box 12.2) was first described in Japan in 1967. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in the developed world. KD usually affects children under the age of 12. The typical clinical features are described in Box 12.3. The most serious feature of KD is coronary artery disease; aneurysms occur in one-fifth of untreated patients and may lead to myocardial infarction. They can be detected by echocardiography and, in severe circumstances, coronary reperfusion strategies are required.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree