(1)

Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin Ospedale Molinette, Turin, Italy

Abstract

The origin of the ophthalmic artery and the several connections of the intraorbital vessels with those of the intracranial and craniofacial areas explain the frequent involvement of the ophthalmic artery and ophthalmic veins in vascular malformations located outside of the orbita.

The origin of the ophthalmic artery from ICA and the several connections of the intraorbital vessels with those of the intracranial and craniofacial areas explain the frequent involvement of the ophthalmic artery and ophthalmic veins in vascular malformations located outside of the orbit.

We summarize here all these pathological conditions, already presented in detail in the corresponding chapters. In addition, we describe some specific pure intraorbital vascular malformations.

As far as it concerns the ophthalmic artery and its branches, they can be involved in DAVFs especially of the frontobasal area (Sect. 13.7) and in brain AVM such as in the Wyburn–Mason syndrome (Sect. 12.7.3) and can contribute to the supply of AVM of the craniofacial region (Sect. 3.9.1 and Fig. 3.16). Pure intraorbital AVM are rare (Smoker et al. 2008). Angiography is essential in the diagnosis of this pathology, and it is also useful in the differential diagnosis of other richly vascularized orbital tumors such as hemangiopericytoma, hemangioblastoma, and meningioma.

The typical ophthalmic aneurysm is the carotid-ophthalmic arising at the origin of the ophthalmic artery from ICA or close to it (Sect. 11.6.3). More distally located aneurysms are very rare. They can originate from the intracranial portion of the artery (Yanaka et al. 2002) or be more distally, intraorbitally located (Meyerson and Lazar 1971; Day 1990; Ogawa et al. 1992; Kikuchi and Kowada 1994; Ernemann et al. 2002; Dehdashi et al. 2002). Cases of fusiform, probably dissecting aneurysms extending through the optic canal, have also been described (Piche et al. 2005; Choi et al. 2008). Visual disturbances and SAH in cases of rupture of the intracranial segments are the typical symptoms.

The ophthalmic veins can be involved as a venous drainage in DAVFs of the cavernous and para-cavernous sinuses (Sect. 13.7) and in direct carotid-cavernous sinus fistulae (Chap. 14). Craniofacial AVMs can drain in the ophthalmic veins.

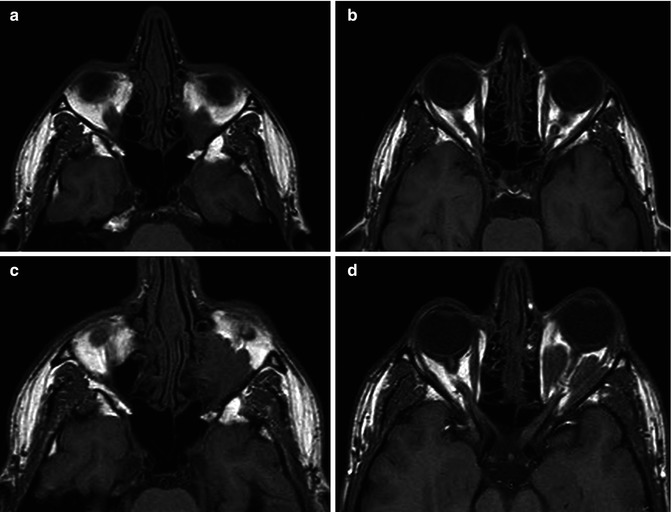

A specific intraorbital malformation is the so-called orbital varix. This is characterized by a single dilated venous channel or by a network of small veins all draining commonly, but not always in the SOV (Smoker et al. 2008). It can intermittently fill and collapse leading to an acute temporary exophthalmos. This occurs in particular conditions such as lowering the head or following a cough or exertion activities. Hemorrhage and thrombosis can occur (Mafee 2003). The malformation can be associated with other intracranial venous anomalies. CT and/or MR without and with contrast medium in supine and prone positions or associated with Valsalva maneuver or jugular vein compression can clarify the diagnosis (Figs. 23.1 and 23.2). The carotid angiogram, commonly, fails to demonstrate the malformation, which is, however, sometimes visible when large connections with the intracranial venous system are present. Furthermore, the angiogram can show the presence of other intracranial venous malformations (Figs. 23.3 and 23.4).