Vascular Disorders

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

♦ disorders that affect the vessels of the circulatory system

♦ pathophysiology and treatments related to these disorders

♦ diagnostic tests, assessment findings, and nursing interventions for each disorder.

A look at vascular disorders

Vascular disorders can affect both arteries and veins. Arterial disorders include aneurysms, which result from weakening of the arterial wall, and arterial occlusive disease, which commonly results from atherosclerotic narrowing of the artery’s lumen. Thrombophlebitis results from inflammation or occlusion of the veins. Patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) also experience compromised blood flow from atherosclerosis much like coronary artery disease (CAD).1 The same risk factors for CAD apply to PAD. Risk factors include stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and cardiovascular death. PAD can be life threatening if blockages in the vessels compromise circulation and oxygen delivery.

Aortic aneurysm

An aneurysm is an abnormal dilation in a weakened arterial wall. Aortic aneurysms typically occur in the abdominal aorta between the renal arteries and the iliac branches, but the thoracic aorta may also be affected.2

Bumpy road ahead

Major complications of aortic aneurysm include hemorrhage, MI, renal failure, embolus, cerebrovascular insufficiency, circulatory collapse, and death.3

|

What causes it

The exact cause of an aortic aneurysm is unclear, but several factors place a person at risk, including:

• smoking

• hypertension

• advancing age

• connective tissue disorders

• atherosclerosis

• family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

• diabetes

• trauma

• heredity

• male sex.

Risk for aneurysm rupturing

• aneurysm larger than 6 cm

• smoker

• female gender

• uncontrolled hypertension

How it happens

An aortic aneurysm is a potentially life-threatening condition. An aneurysm is a dilation of a blood vessel. The aorta begins to dilate with age. The average size of the aorta is 2 to 3 cm. The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an aneurysm.4

Aneurysms arise from a defect in the middle layer of the arterial wall (tunica media, or medial layer). When the elastic fibers and collagen in the middle layer are damaged, stretched, then segmental dilation occurs. As a result, the medial layer loses some of its elasticity, and it fragments. Smooth muscle cells are lost, and the wall thins.

Thin and thinner

The thinned wall may contain calcium deposits and atherosclerotic plaque, making the wall brittle. As a person ages, the elastin in the wall decreases, further weakening the vessel. If hypertension is present, dilation of the arterial wall occurs more quickly, resulting in additional weakening.

Wide vessel, slow flow

When an aneurysm begins to develop, lateral pressure increases, causing the vessel lumen to widen and blood flow to slow. A thrombus may form within the dilated area. Over time, mechanical stressors contribute to elongation of the aneurysm.

Blood forces

What to look for

Most patients with an aortic aneurysm are asymptomatic until the aneurysm grows and compresses the surrounding tissue.5 A large aneurysm may produce signs and symptoms that mimic those of an MI, renal calculi, lumbar disk disease, and duodenal compression. Many aneurysms are accidentally found during routine screenings, physical exams, or imaging studies to evaluate an unrelated condition.2

When symptoms arise

Usually, if the patient exhibits symptoms, it is because of rupture, expansion, embolization, thrombosis, or pressure from the mass on surrounding structures. Rupture is more common if the patient also has poorly controlled hypertension or if the aneurysm is 6 cm or larger. A patient with a leaking or ruptured aneurysm may report sharp, severe, or tearing pain in the back, abdomen, or flank.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

The patient with an AAA may experience:

• generalized, steady abdominal pain

• lower back pain that’s unaffected by movement

• gastric or abdominal fullness

• palpable, pulsating mass in the periumbilical area (if the patient isn’t obese)

• systolic bruit over the aorta on auscultation of the abdomen

• bruit over the femoral arteries

• hypotension (with aneurysm rupture).

Thoracic aortic aneurysm

If the patient has a suspected thoracic aortic aneurysm, assess for:

• complaints of substernal pain, possibly radiating to the neck, back, abdomen, or shoulders

• hoarseness or coughing

• difficulty swallowing

• difficulty breathing

• hemoptysis

• hematemesis

• unequal blood pressure and pulse when measured in both arms

• aortic insufficiency murmur.

Acute expansion

When acute expansion of an aortic aneurysm exists, assess for:

• abdominal, pelvic, flank, or back pain

• limb ischemia

|

|

• pulsatile abdominal mass

• hypotension

• acute heart failure.

When an acute expansion of a thoracic aortic aneurysm exists, assess for:

• severe hypertension

• neurologic changes

• a new murmur of aortic insufficiency

• right sternoclavicular lift

• jugular vein distention

• tracheal deviation

• acute onset of heart failure

• sharp, tearing pain in the chest or upper back.

What tests tell you

Most aneurysms are found incidentally during a physical examination or during testing for other medical problems. No specific laboratory test to diagnose an aortic aneurysm exists. However, these tests may be helpful:

• If blood is leaking from the aneurysm, a complete blood count (CBC) may reveal leukocytosis and a decrease in hemoglobin level and hematocrit.

• Abdominal ultrasound or echocardiogram may be used to determine the size, shape, length, location, and blood flow patterns of the aneurysm.2

Telltale TEE

• Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) allows visualization of the thoracic aorta. It’s commonly combined with Doppler flow studies to provide information about blood flow.

• Anterioposterior and lateral X-rays of the chest or abdomen can be used to detect aortic calcification, and widened areas of the aorta may be visualized.

• Computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can disclose the aneurysm’s size in detail and the effect on nearby organs.4

• Serial duplex ultrasound at 6- to 12-month intervals can monitor the growth of small aneurysms.

• Arteriography is the gold standard for diagnosing the aneuryms’s size and blood flow to the surrounding vessel.

How it’s treated

Aneurysm treatment usually involves open surgery or an endovascular approach. The choice of repair is dependent on presenting symptoms and the urgency of the condition.

Aortic aneurysms larger than 5.5 cm or ruptured require immediate open surgical resection and replacement of the aortic section

using a vascular or dacron graft. Treatment for a ruptured aortic aneurysm includes fluid resuscitation and blood replacement.4 However, keep these points in mind:

using a vascular or dacron graft. Treatment for a ruptured aortic aneurysm includes fluid resuscitation and blood replacement.4 However, keep these points in mind:

• If the aneurysm is small and produces no symptoms, surgery may be delayed, with regular physical examination and ultrasound to monitor its progression.

• Large aneurysms and those in symptomatic patients, who are at risk for rupture, need immediate repair.

• A nonsurgical procedure called an endovascular grafting may be an option for a patient with an AAA. (See Endovascular grafting repair for AAA.)

• Medications to control blood pressure and dyslipidemia, relieve anxiety, and control pain are also prescribed.

Rush to respond to rupture

Rupture of an aortic aneurysm is a medical emergency requiring prompt treatment, including:

• resuscitation with fluid and blood replacement

• Intravenous (IV) propranolol to reduce myocardial contractility

• IV nitroprusside to reduce blood pressure and maintain it at 90 to 100 mm Hg systolic

• analgesics to relieve pain

• an arterial line and indwelling urinary catheter to monitor the patient’s condition preoperatively.

|

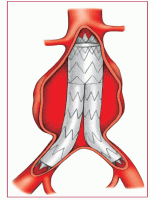

Endovascular grafting repair for AAA

Endovascular grafting, shown at right, is an invasive procedure in which the walls of the aorta are reinforced to prevent expansion and rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The stent graft is threaded through the femoral artery and placed within the AAA. Blood flow is then routed through the graft and doesn’t enter the aneursym sac. The procedure can be done using local or regional anesthesia. Because the procedure is performed percutaneously, it’s less invasive than open surgical repair.

The patient is instructed to walk the first day after surgery and is discharged from the hospital in 1 to 3 days.

|

What to do

• Collaborate care with a skilled team, which may include emergency medical personnel, a vascular surgeon, cardiologist, and nutritional and physical therapists.

• Assess the patient’s vital signs, especially blood pressure, every 2 to 4 hours or more frequently, depending on the severity of the condition. Monitor blood pressure and all pulses in the extremities and compare findings bilaterally. If the difference in systolic blood pressure exceeds 10 mm Hg, notify the doctor immediately.

• Assess cardiovascular status frequently, including heart rate, rhythm, electrocardiogram, and cardiac enzyme levels. An MI is one of the most common complications.

• Obtain blood samples to evaluate kidney function by assessing blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels. Measure intake and output, hourly if necessary, depending on the patient’s condition.

• Monitor CBC for evidence of blood loss, including decreased hemoglobin level, hematocrit, and red blood cell (RBC) count.

• If the patient’s condition changes acutely, obtain an arterial blood sample for arterial blood gas analysis, as ordered, and monitor cardiac rhythm. Assist with arterial line insertion to allow for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Assist with insertion of a pulmonary artery catheter to assess hemodynamic status.

• Administer ordered medications to control hypertension. Provide analgesics to relieve pain, if present.

• Observe the patient for signs of rupture, which may be immediately fatal. Watch closely for any signs of acute blood loss: decreasing blood pressure; increasing pulse and respiratory rates; cool, clammy skin; restlessness; and decreased level of consciousness.

• Explain the surgical procedure and the expected postoperative care to the patient and family.

• Reinforce instructions for controlling blood pressure. Stress the importance of medications and diet therapy and the need for smoking cessation.

Rupture response

• If rupture occurs, insert a large-bore IV catheter, begin fluid resuscitation, and administer nitroprusside IV as ordered, usually to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 70 to 80 mm Hg. Also administer propranolol IV as ordered until the heart rate ranges from 60 to 80 beats/minute. Expect to administer additional doses every 4 to 6 hours until oral medications can be used.

• If the patient is experiencing acute pain, administer morphine 2 to 10 mg IV as ordered.

• Prepare the patient for emergency surgery.

|

After surgery

• Administer nitroprusside or nitroglycerin and titrate to maintain a normotensive state.

• Perform meticulous pulmonary hygiene measures, including suctioning, oral care, chest physiotherapy, and deep breathing.

• Provide continuous cardiac monitoring.

• Assess urine output hourly.

• Maintain nasogastric tube patency to ensure gastric decompression.

• Assist with serial Doppler examination of all extremities to evaluate the adequacy of blood flow and to detect embolization.

• Assess for signs of reoccurrence of poor arterial perfusion by looking for pain, paresthesia, pallor, numbness, pulselessness, paralysis, and poikilothermy (coldness).

• Advise the patient about activity restrictions, such as no pushing, pulling, or lifting heavy objects until cleared by the physician.

• Document cardiac, respiratory, and neurovascular statuses; wound appearance and care; intake and output; and vital signs or hemodynamic parameters. Document patient teaching provided as well as the patient’s understanding of the instructions.

Peripheral arterial disease

PAD is a marker of systemic atherosclerosis. Most patients who have peripheral arterial or vascular disease also have CAD.6 It may affect large vessels, such as the aorta and its branches, or the subclavian, mesenteric, renal, or peripheral vessels. It may be acute or chronic. (See Possible sites of major artery occlusion.)

Major complications of PAD include severe pain, limb paralysis, infection, gangrene, limb loss, and death.3

What causes it

Risk factors for PAD include smoking, aging, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and family history of known atherosclerosis at other sites: renal, carotid, or coronary.7 A diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is also associated with an increased risk of developing PAD.8,9

Causes of PAD include:

• emboli formation

• thrombosis

• atherosclerosis.

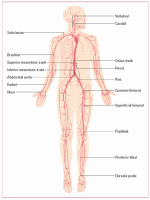

Possible sites of major artery occlusion

This illustration points out the possible sites of major artery occlusion.

|

How it happens

In PAD, obstruction or narrowing of the lumen of the aorta, its major branches, and peripheral circulation causes an interruption of blood flow. This usually affects the lower extremities.

Location and timing

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree