Chapter 13

Vascular Anomalies

E. Kate Waters and William D. Adair

Leicester Royal Infirmary, UK

Table 13.1 The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification of vascular anomalies.

| Vascular tumours | Vascular malformations |

Haemangioma

Tumours

Malignant tumours

| Capillary

Venous

Lymphatic

Arterial

Combined

Syndrome associated

|

Source: Dompartin et al. (2010). Reproduced by permission of SAGE Publications.

Vascular tumours

Infantile haemangiomas (strawberry naevi) are the most common childhood vascular tumour, occurring in 12% of infants. Typically, these lesions are not visible at birth but rapidly enlarge during a proliferative phase up to the age of 6 months. Growth characteristically slows down till the age of 1 year and there is subsequent gradual involution of the lesion with complete involution in 50% of individuals at 5 years of age and in 90% of individuals at 9 years. The majority of cases will have subtle residual skin changes.

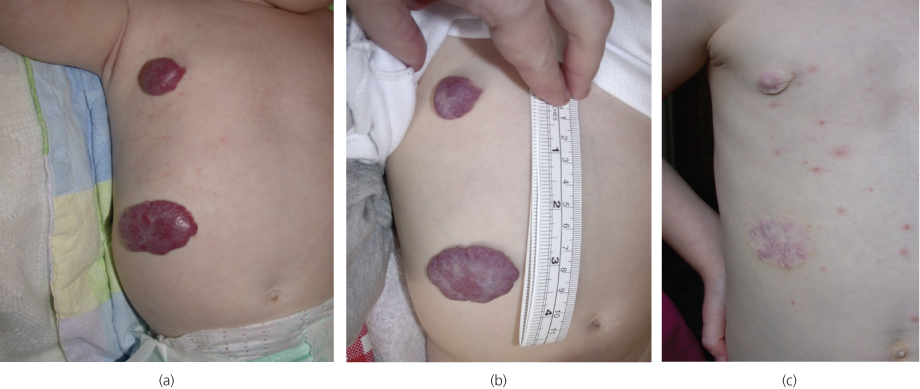

Diagnosis is usually made on clinical history and examination findings alone without the need for imaging. Infantile haemangiomas with superficial dermal components have a classic strawberry appearance (Figure 13.1), while deeper lesions not involving subcutaneous tissue can have a blue appearance.

Figure 13.1 Infantile haemangioma (strawberry naevus): (a) at 5 months, (b) at 9 months and (c) at 5 years (with additional varicella).

Management of haemangioma is conservative in the majority of cases with even larger lesions naturally involuting over time. Recently, treatment with topical beta-blocker has been found to be effective for superficial lesions. Intervention is indicated if complications occur such as mass effect on adjacent structures, in particular, the airway or orbits, consumptive coagulopathy (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome), ulceration and bleeding.

High output cardiac failure is a rarely occurring complication of infantile haemangioma requiring medical treatment and embolisation of the capillary bed. Other vascular tumours include congenital haemangioma, present and fully formed at birth, pyogenic granuloma and tufted angioma.

Vascular malformations

Vascular malformations develop as a result of abnormal vessel angiogenesis. Therefore, unlike vascular tumours, they are dysplastic rather than proliferative. They are always present at birth, although they may not be clinically evident for months or years. These lesions can undergo periods of enlargement particularly during puberty, pregnancy or following trauma and do not spontaneously regress. It is usually possible to differentiate between low- and high-flow malformations on clinical history and examination. Imaging being used to confirm diagnoses and to plan any subsequent treatment (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Classification of vascular malformations according to their flow dynamics.

| High-flow vascular malformations | Low-flow vascular malformations |

| Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) | Venous malformations (VMs) Lymphatic malformations (LMs) Combined malformations (CVM, CLVM) |

Source: McCafferty and Jones (2011). Reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

Low-flow vascular malformations

Capillary malformation

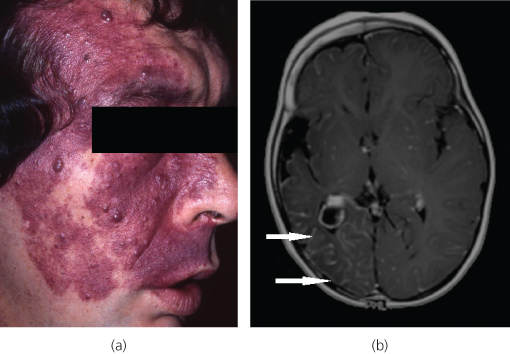

Salmon patch (erythema nuchae) and port wine stains (naevus flamus) are examples of capillary malformations (CMs). Salmon patches are very common, occurring in approximately 40% of newborns. They are red macular lesions commonly involving the nape of the neck, the upper eyelids or on the forehead between the eyebrows. They become more prominent when the infant cries or has a fever, and usually disappear by 2 years of age. Port wine stains (Figure 13.2a) occur in 0.3% of newborns and are well-demarcated purple or dark red patches most commonly affecting the face. They are usually dermatomal in distribution and unilateral, growing proportionately over time with the child. They do not regress spontaneously and can evolve from being flat to become nodular and thickened. Associated bone and soft tissue hypertrophy can occur. Port wine stains are usually an isolated abnormality, but can occur as part of the Sturge–Weber syndrome. This is the association of a capillary vascular malformation affecting one branch of the trigeminal nerve of the face, with a leptomeningeal vascular malformation and vascular malformation of the eye (Figure 13.2b).

Figure 13.2 (a) Port wine stain. (b) Port wine stains can be associated with leptomeningeal vascular malformations in Sturge–Weber syndrome. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted axial MRI demonstrates right-sided prominent leptomeningeal enhancement (arrows) of leptomeningeal haemangioma, with associated cerebral hemiatrophy.

Venous malformations

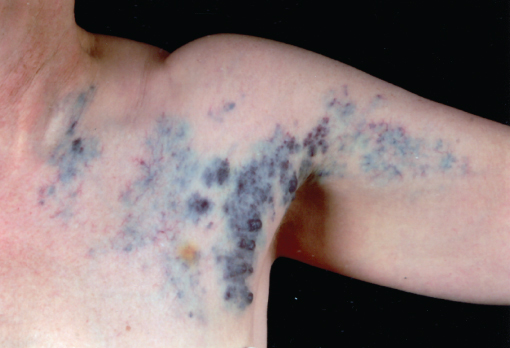

Venous malformations (VMs) consist of abnormal venous channels of varying size within a connective tissue and fatty stroma, which connect with adjacent veins. Local intravascular coagulopathy is a feature, which combined with slow venous flow makes them prone to thrombosis. Pain and swelling secondary to thrombosis are common presenting symptoms of VMs in late childhood or early adulthood. Symptoms may also relate to the size and site of VM. For example, those located within muscles can be painful on movement. The lesions are non-pulsatile, often with associated swelling and blue discolouration of the skin, and can be tender (Figure 13.3). They classically distend when dependent and empty on elevation of the lesion, depending on the number and integrity of the venous channels. Firm small calcified phleboliths may be palpable secondary to thrombosis. Rarely, VMs are multiple, located in the skin and visceral organs, as part of the blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome.

Figure 13.3 Superficial venous malformation. The blue papular parts of the lesion can be emptied with compression and spontaneously refill.

Lymphatic malformations

Lymphatic malformations are the second most common vascular malformation. Arising from lymphatic vessels, the majority are present at birth with 90% seen at 2 years of age. Lymphatic malformations are most commonly located in the neck, where they are often known as cystic hygromas (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4 Lymphangioma (cystic hygroma).

Mixed malformations

There is considerable overlap between venous and lymphatic malformations with many lesions having various different tissue morphologies within different areas of the same malformation.

High-flow vascular malformations

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) consists of direct connections between the arterial and venous system, bypassing the normal capillary bed of organs and tissues, and any malformation with such an arterial component is considered high flow.

AVMs are present at birth but may not become apparent until puberty or adulthood. Puberty, pregnancy and trauma can induce rapid enlargement of these lesions. The Schobinger classification of AVMs grades lesions according to symptomatology (Table 13.3). Pain, bleeding and ulceration are common presenting symptoms: high output cardiac failure is rare. Clinical examination usually reveals a warm, pulsatile mass with skin discolouration. Limb overgrowth may be noted due to hypertrophy or venous hypertension (Figure 13.5).

Table 13.3 Schobinger classification of arteriovenous malformation by symptoms.

| Schobinger stage | Symptoms/clinical findings |

| I Quiescent | Stable lesion, pink/bluish stain, warmth. AV shunting seen on Doppler US |

| II Expanding | Type I plus enlargement, pulsations, thrill, bruit, tortuous tense veins |

| III Symptomatic | Type II plus pain, bleeding, ulceration, tissue necrosis, functional problems |

| IV Decompensating | Type III plus high output cardiac failure |

Source: McCafferty and Jones (2011). Reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

Figure 13.5 AVM within the anterior compartment of the leg. Note the skin changes secondary to venous hypertension as well as small ulcers (arrows) that presented periodically with life-threatening haemorrhage.

Imaging vascular malformations

The diagnosis of vascular anomalies is mostly through clinical assessment, but a handheld Doppler ultrasound is a useful adjunct to gauge the presence of arterial flow.

Duplex ultrasound is an accessible, non-invasive first-line investigation that can give more specific information regarding exact location, presence of vascular spaces and flow characteristics.

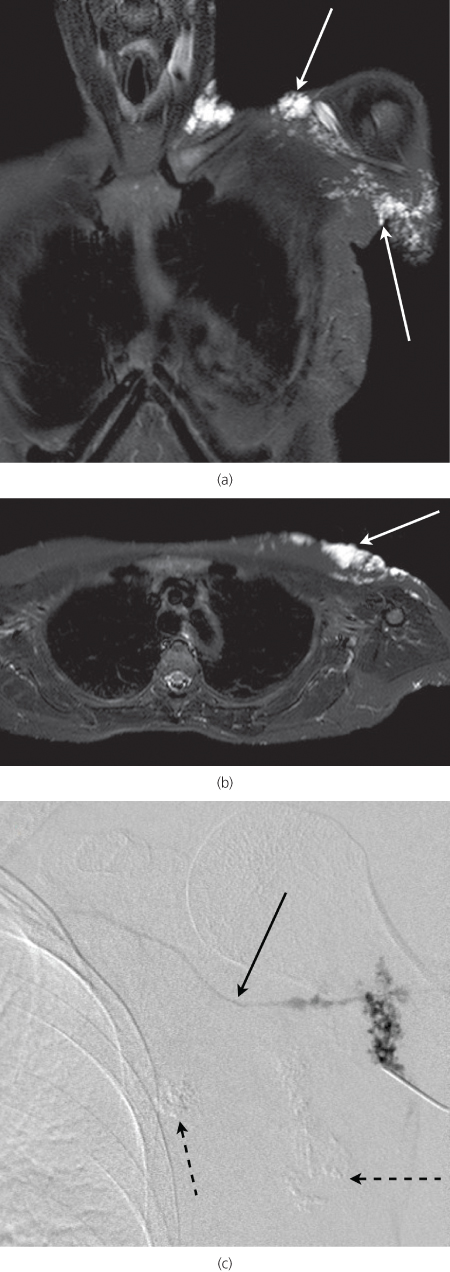

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) gives detailed analysis of lesions without ionising radiation and can more fully assess the extent of infiltrative and deeper lesions. MRI is also useful in evaluation of those vascular anomalies that are clinically indeterminate and can aid in their differentiation from more sinister lesions. Detailed information regarding the anatomical extent, and vascular supply, can be obtained as a prelude to treatment (Figure 13.6a and b).

Figure 13.6 Fat saturated coronal (a) and axial (b) T2-weighted MRI sequences through the chest. The venous malformation shown in Figure 13.3 is clearly visible (arrows). (c) Venogram of venous malformation. Note draining vein (solid arrow). Two areas have been sclerosed at the same session (dotted arrows).

Computed Tomography (CT) is not routinely used in the assessment of vascular anomalies. The radiation dose of a diagnostic CT is justified only in rare circumstances.

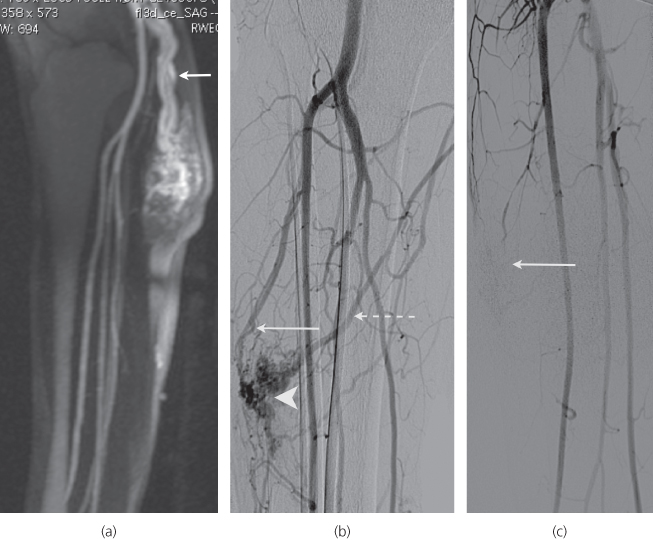

Catheter venography/angiography is essential for treatment planning of both low- and high-flow malformations, providing detailed information about flow characteristics and feeding and draining vessels. It is usually performed during the same session as the treatment (Figure 13.7b and c).

Figure 13.7 (a) MR angiogram of leg AVM (same patient as Figure 13.5). (b) Catheter angiogram: note nidus (arrowhead), major feeding artery (arrow) and draining vein (dotted arrow). (c) Catheter angiogram post embolisation with Onyx™—note obliteration of the nidus (arrow).

Management of vascular malformations

Low-flow vascular malformations

There are various treatment options for low-flow vascular malformations, but the majority of patients with these lesions can be managed conservatively. The use of cosmetics and camouflage creams, analgesia for episodes of pain, venous compression stockings and antibiotics for infections associated with lymphatic malformations has a role. Avoidance of the combined oral contraceptive to reduce thrombotic risk may be appropriate. Counselling and screening for associated genetic syndromes might be required.

Venous malformations

Percutaneous sclerotherapy is the primary treatment if conservative measures have failed to manage symptoms, in particular pain. Sclerotherapy aims to obliterate the venous lumen and shrink the lesion. Following direct puncture of the venous channels using ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance, agents such as ethanol, bleomycin or sodium tetradecyl sulphate are injected (Figure 13.6c).

Swelling and pain in the region of the malformation generally increases in the first 2 weeks post procedure, and patients must be warned of the expected time course of symptom improvement, which can take several months. Extensive VMs may require multiple treatment sessions. Approximately 20% of the patients can expect to have complete relief of symptoms after one course of treatment, 60% should have a decrease in symptoms, while 20% receive no therapeutic benefit. Complications occur in up to 15% of the cases. These include skin necrosis and nerve damage (which can be transient). PE (pulmonary embolism), DVT (deep vein thrombosis), DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation) and death are very rare post sclerotherapy.

Lymphatic malformations

Percutaneous sclerotherapy using a variety of sclerosants (notably bleomycin or doxycycline) can achieve satisfactory long-term outcomes, particularly in lesions with a macro-cystic component. There are difficult-to-treat subsets of lymphatic malformations that may also require surgical debulking.

High-flow vascular malformations

High-flow vascular malformations are the most difficult to treat, with high rates of recurrence and frequently occurring complications. As a result, treatment should be reserved for symptomatic lesions, i.e. Stage III and IV Schobinger classification lesions (Table 13.3). Surgical excision or debulking has limited value in the management of most AVMs, and should surgery become necessary, results are often disappointing.

Radiological embolisation is the first-line treatment choice. Peri-procedure pain from preferred agents and long procedure times necessitate general anaesthesia. Embolisation aims to obliterate the arteriovenous shunts. Various liquid embolics can be used including ethanol, sodium tetradecyl sulphate or Onyx (a liquid ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer that forms a cast on contact with blood; it has the unusual side effect of giving the patient a garlic-like odour for 24–48 h after treatment). These agents can be delivered to the AVM by transarterial or transvenous access or by direct injection into the lesion (Figure 13.7a–c).

Particulate or large embolic devices such as embolisation coils and Amplatzer plugs are rarely used, although the latter are most useful in the treatment of pulmonary AVMs, most commonly associated with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

The majority of lesions will require more than one embolisation treatment and the patient must be consented for this. Complications are the same as for low-flow sclerotherapy but are likely to occur with increased incidence in high-flow lesions. High-flow vascular malformations have the highest rate of recurrence, particularly with insufficient or incorrect treatment of the original lesion. Each patient should be followed up for at least 2 years to detect any sign of AVM recurrence and to monitor for complications.

Conclusions

- Vascular anomalies are divided into vascular tumours and vascular malformations.

- Vascular malformations are a challenging group of conditions, best managed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise primarily from interventional radiologists and vascular surgeons as well as dermatologists and plastic surgeons.

- The diagnosis and management of these lesions is made mainly on clinical assessment, correlated with flow dynamics on Doppler ultrasound confirming the low- or high-flow nature of the lesions.

- MRI can be useful to confirm the diagnosis, exclude other pathologies, and plan treatment where necessary.

- The majority of vascular malformations can be managed conservatively. Treatment is reserved for those with significantly symptomatic lesions and is planned on a case-by-case basis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree