Chapter 2

Vascular Anatomy of the Central and Peripheral Veins

Central venous catheter placement is a significant and growing proportion of the interventional radiologist’s workload. The use of long-term vascular access devices has increased dramatically over the last decade. Central catheters are needed for infusion of fluids and other agents, such as chemotherapeutic agents, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and antibiotics, as well as for hemodialysis and pheresis and many other less common uses.

One important aspect for the successful and safe placement of central catheters is a knowledge of the normal anatomy of the central and other veins and their variants. A brief description of the embryologic development of the central and peripheral veins is helpful to understanding the venous anatomy because anomalies of the veins are rather common. Anatomic variants of venous drainage occur because of abnormalities in formation or regression of the primitive venous system during the embryonal development. Some veins that should regress, persist, and the converse is also true.

In general, the veins preferred for placement of central and peripheral venous access catheters are the internal jugular veins in the neck, the axillary and subclavian veins in the chest, the cephalic and basilic veins in the upper extremities, and the superficial femoral and common femoral veins in the lower extremities. When all these veins are depleted for catheterization, the inferior vena cava (IVC) can be accessed by direct translumbar or transhepatic puncture. Furthermore, other veins, such as the azygous, hemiazygous, or collateral venous channels, can be used if other accesses are no longer available.

VENOUS ANATOMY OF THE UPPER EXTREMITY

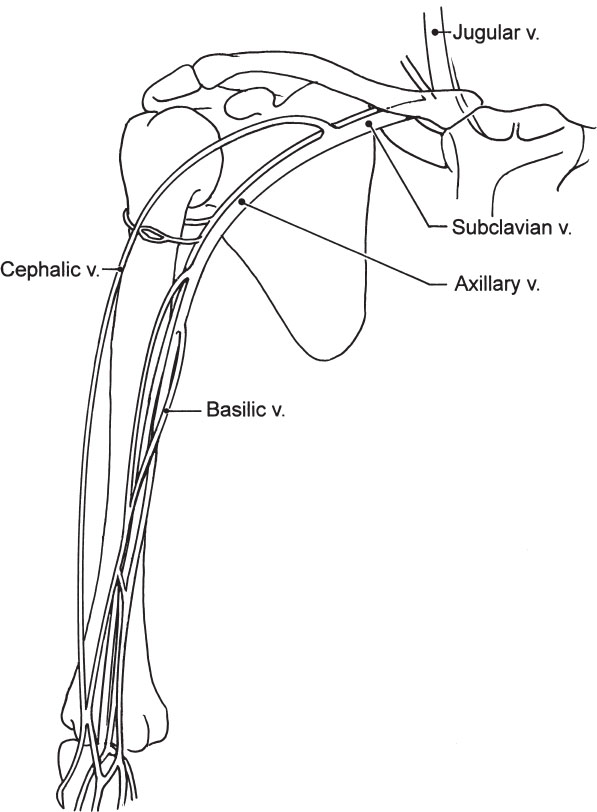

The veins of the upper extremity are organized into superficial and deep systems. The superficial system consists of the basilic vein medially and the cephalic vein laterally.

The basilic vein is the larger of these, and it courses along the medial aspect of the forearm and arm. It is formed by the junction of the common ulnar and median basilic veins. The basilic vein becomes the axillary vein at the level of the inferior border of the teres major muscle. The axillary vein courses through the axilla and becomes the subclavian vein, which joins the internal jugular vein and becomes the innominate or brachiocephalic vein. The right and left innominate veins join together in the chest and form the superior vena cava (SVC).1–3

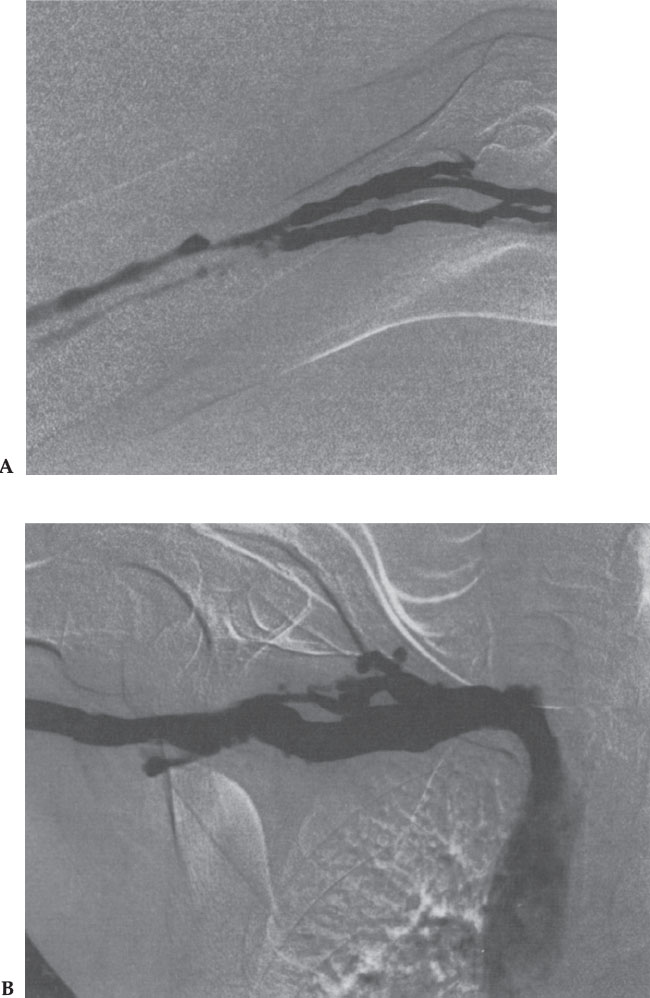

The cephalic vein courses along the lateral aspect of the arm, superficial to the biceps muscle, before crossing medially between the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles to join the axillary vein. The cephalic vein is smaller than the basilic vein and turns at an acute angle just before entering the axillary vein, making catheterization of this vein more difficult. Therefore, the cephalic vein is not the first choice for placement of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs). When the basilic vein is not available or is occluded, the cephalic vein can be used (Figs. 2–1 and 2–2).1–3

The deep veins of the upper extremity course parallel to the arteries and consist of paired radial, ulnar, and interosseous veins in the forearm and brachial veins in the arm. The brachial veins join the axillary vein in the axilla. The brachial veins are the only deep veins in the arm that are large enough for central access. Their deep location and proximity to the brachial artery, however, make them less than ideal for venous access, but they can be used whenever the superficial veins are not available.

Figure 2–1 Diagram of the veins of the upper extremity. The basilic and cephalic veins and the confluence are noted.

Figure 2–2 (A) Basilic vein in the arm. (B) Right axillary, subclavian, and brachiocephalic veins and superior vena cava.

HELPFUL HINTS

Variations of the venous anatomy are common. In fact, variability of size and number of veins is the rule rather than the exception. Furthermore, anatomic differences between right and left sides are common and expected, indeed.

VENOUS ANATOMY OF THE NECK

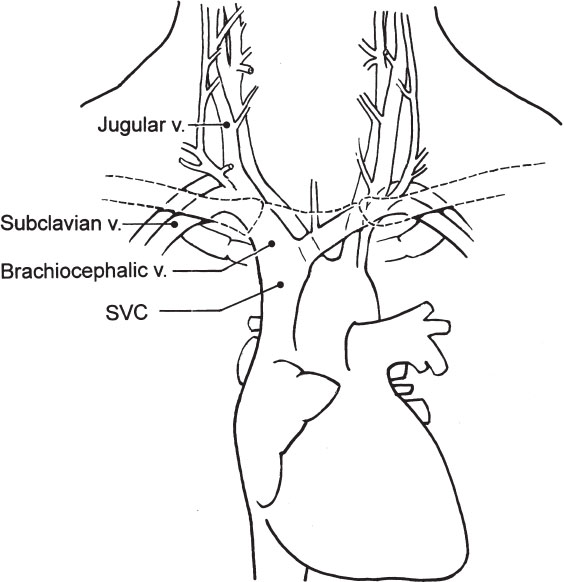

The internal jugular veins (IJVs) are continuations of the sigmoid sinuses, which drain the major intracranial sinuses. The IJVs usually are discrepant in size, with the right one often larger in diameter than the left one. The IJVs course downward and laterally in the neck, from the jugular foramen at the base of the skull to the base of the neck to join the subclavian veins in the thorax to form the brachiocephalic or innominate veins. The IJVs receive several tributaries, such as the facial, lingual, thyroidal, and other veins. The IJVs are located posterolateral to the internal carotid arteries just below the base of the skull; however, as they course downward toward the chest, the IJVs are located anterolateral to the artery. Usually, there is a valve at its junction with the subclavian vein (Fig. 2–3).4

Figure 2–3 Diagram of the veins of the neck and chest. The internal jugular veins are seen joining the subclavian veins to form the brachiocephalic or innominate veins. The superior vena cava (SVC) is formed by the confluence of the brachiocephalic or innominate veins.

As mentioned in other chapters, ultrasound guidance is preferred for access of the IJV; however, if ultrasound is not available, a “blind” puncture can be made. There are several ways to puncture the IJV, depending on the relationship of the vein to the sternocleidomastoid muscles.

• The anterior approach includes palpating the carotid artery and puncturing the vein just lateral to the carotid artery. The puncture traverses the belly of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

• The middle approach is made at the apex of the triangle formed by the anterior and posterior bellies of the sternocleidomastoid and the clavicle. The needle is directed toward the ipsilateral nipple.

• The posterior approach is done posterior to the posterior belly of the sternocleidomastoid, in the lower neck, and the needle is directed toward the sternal notch (Fig. 2–4).