Chapter 9

Varicose Veins

Greg S. McMahon and Mark J. McCarthy

Department of Vascular & Endovascular Surgery, Leicester Royal Infirmary, UK

Introduction

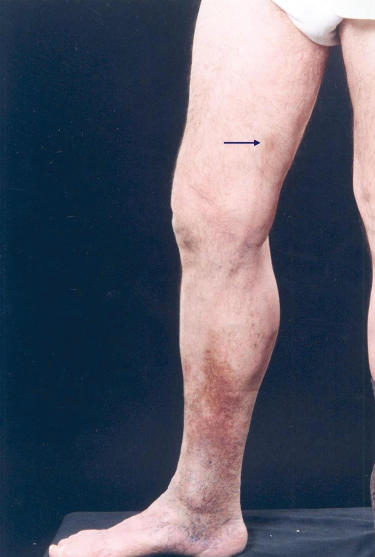

Varicose veins are common. While estimates vary, prevalence is probably in the region of a quarter to one-third of the adult population, and in 2009, over 30 000 varicose vein procedures were carried out on the National Health Service (NHS). The word ‘varicose’ describes (often tortuous) dilatation of a vein, a process that, while theoretically affecting any vein in the body, is most commonly encountered in the leg, due to the hydrostatic pressure of upright positioning (Figure 9.1). The symptoms of varicose veins are wide-ranging, from none through to mild cosmetic issues, to very severe symptoms including ulceration.

Figure 9.1 Trunal varices are varicosities in the line of the long (a) or short (b) saphenous vein or their major branches. Reticular veins (c) are dilated tortuous subcutaneous veins not belonging to the main branches of the long or short saphenous vein and telangiectasia (c) are intra-dermal venules less than 1 mm in size. (c) Demonstrates both reticular veins and telangiectasia. The latter are also referred to as ‘spider veins’, ‘star bursts’, ‘thread veins’ or ‘matted veins’.

Pathophysiology

Varicose veins are almost always the result of superficial venous reflux or incompetence (i.e. flow retrograde to the physiological norm), which is usually due to failure of the venous valve mechanism. Valve failure is either primary—a dysfunction of the leaflets or annulus itself—or secondary—a weakness in the vein wall that results in widening of the valve leaflets, and ensuing incompetence due to their incomplete apposition. While it is likely that varicose veins result from a combination of these mechanisms, there is evidence to suggest that patients with varicose veins do indeed have an inherent reduction in vein wall elasticity. This would, in part, explain why recurrence of varicose veins is so common following treatment (5%). Furthermore, it is proposed that there is a hereditary component to varicose veins; the observation that the children of two parents with varicose veins have a 90% chance of developing them is compelling.

There are other risk factors for the development of varicose veins including female sex, prolonged standing, increased height, obesity (through venous hypertension), increasing age and multiparity. More rarely, varicose veins are the result of deep vein thrombosis, pelvic tumour or vascular malformation.

Classification

The distinction between ‘thread’ or ‘spider’ veins and other varicosities is simply based on size, with the former referring to intra-dermal venules of less than 1-mm diameter (Figure 9.1). Valvular dysfunction can be present in the long (or greater) saphenous or short (or lesser) saphenous veins, or their major tributaries in which case the term ‘trunk’ or ‘truncal’ varicosity is used. Valvular incompetence does not need to be present in one of the trunk veins for large varicosities to occur; where varicose veins develop because of local dysfunction in an unnamed tributary, the veins are sometimes termed ‘reticular’.

The CEAP (clinical, aetiological, anatomical, and pathophysiological) classification (Table 9.1) is now the worldwide standard for describing in detail the clinical features of chronic venous disease. This thorough tool has probably found its niche more as a common language for the comparison of research trials rather than as a widespread clinical aid in daily practice.

Table 9.1 CEAP (clinical, aetiological, anatomical, and pathophysiological) classification of severity and aetiology of lower limb venous disease.

| Clinical classification | Aetiological classification | Anatomical classification | Pathophysiological classification | ||||

| C0 | No signs of venous disease | Ec | Congenital | As | Superficial veins | Pr | Reflux |

| C1 | Reticular veins | Ep | Primary | Ap | Perforator veins | Po | Obstruction |

| C2 | Varicose veins | Es | Secondary (post-thrombotic) | Ad | Deep veins | Pr,o | Reflux and obstruction |

| C3 | Oedema | En | No venous cause identified | An | No venous location identified | Pn | No venous pathophysiology identified |

| C4a | Pigmentation or eczema | ||||||

| C4b | Lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche | ||||||

| C5 | Healed venous ulcer | ||||||

| C6 | Active venous ulcer | ||||||

| S | Symptomatic | ||||||

| A | Asymptomatic | ||||||

Clinical presentation

Varicose veins are often cited as responsible for a variety of symptoms, including sensations of heaviness, burning, cramping, itching, tingling and aching. Such symptoms could equally be attributed to other vascular and non-vascular conditions and it is sometimes difficult to prove a cause-and-effect relationship between varicose veins and a patient’s symptoms. The authors of the Edinburgh Vein Study investigated this uncertainty and concluded that even in the presence of trunk varicosities, most lower limb symptoms probably do not have a venous cause. It is in the management of patient expectation that this finding has its important implication.

There is no doubt, however, that varicose veins can be responsible for significant changes in the skin of the lower leg, and this is usually best demonstrated at the ankle. The skin changes are thought to be the result of abnormal pressures within the venous system induced by the reflux, and subsequent extravasation of blood into the tissues. They range from pigmentation caused by the deposition in the skin of haemosiderin (Figure 9.2), eczema (Figure 9.3), atrophie blanche (Figure 9.4) and lipodermatosclerosis (Figure 9.5) to overt ulceration (Figure 9.6). Again, when considering patient concerns, it is worthwhile acknowledging that ulceration is actually relatively rare.

Figure 9.2 Skin pigmentation is due to haemosiderin deposition and is most commonly situated above the medial malleolus. However, it may encircle the entire ankle and extend up the leg. In addition, this patient has thrombophlebitis of the long saphenous vein with overlying pigmentation (arrow).

Figure 9.3 Varicose eczema occurs over prominent varicose veins and in the lower third of the leg. It may be dry, scaly and vesicular or ‘weeping and ulcerated’. A generalised sensitisation may occur leading to patches elsewhere.

Figure 9.4 Atrophie blanche results from skin necrosis followed by scarring. Sometimes, small areas of atrophie blanche coalesce to form a large scar.

Figure 9.5 Lipodermatosclerosis involving the medial calf. Acute lipodermatosclerosis presents with a painful, tender, hot, raised red-brown area on the lower leg. The chronic form leads to a hard, indurated area on the lower leg with a palpable edge. The overlying skin is often brown and shiny. The progressive contraction of the gaiter area gives the leg an ‘inverted champagne bottle’ appearance.

Figure 9.6 Venous ulcer, classically seen in the ‘gaiter’ area; lower leg, medial aspect, frequently in an area of skin displaying other evidence of venous incompetence.

While the skin changes are due to abnormalities in venous haemodynamics, other complications of varicose veins are related to the veins themselves. For example, when bleeding occurs, it is most commonly from varicosities at the ankle and can be profuse. Thrombophlebitis is inflammation of the vein wall secondary to thrombosis and is commonly a recurrent phenomenon (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7 Thrombophlebitis caused by a reaction to superficial venous thrombosis. If this approaches the saphenofemoral vein junction, the patient is at risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Patient assessment

History

Why is the patient seeking treatment? Do they have symptoms attributable to varicose veins? Is there an alternative explanation for their leg symptoms? Do they have evidence of arterial, musculoskeletal or neurological pathology, for example? Management of the patient’s concerns and expectations is paramount. It is important also to determine any known history of deep vein thrombosis, or of any conditions that would increase the risk of venous thrombotic events (pregnancies, leg fractures, thrombophilias). This not only helps in distinguishing the aetiology of the presenting complaint, it also has an impact on management decisions; a history of deep vein thrombosis or thrombophlebitis increases the risk of peri-procedural thrombosis should there be intervention.

Examination

Examination has three objectives: to look for a possible cause of the venous insufficiency, to examine the status of the peripheral arterial system, and to examine the varicose veins themselves. An abdominal examination should be performed to look for any masses that could be causing venous obstruction, and an arterial examination should be undertaken to determine the contribution of peripheral vascular disease to the patient’s symptoms and to rule out significant arterial insufficiency that may complicate future management options.

Examination of varicose veins is best performed in a warm room, with the patient standing. In addition to assessing the distribution of the varicosities, scars from previous varicose vein interventions can be looked for. With the evolution of more modern adjuncts, tourniquet tests are generally considered unreliable and are certainly insufficient for the planning of intervention. Although hand-held continuous wave Doppler can reliably identify the site of incompetence in the majority of cases of varicose veins, it is limited in patients with recurrent varicose veins and in instances where there is more than one site of incompetence. Furthermore, it provides no information about the deep venous system.

Investigation

While for many years considered mandatory for patients with skin changes, recurrent varicose veins or deep vein thrombosis, evidence increasingly suggests that colour duplex ultrasonography should actually be carried out on all patients for whom varicose vein intervention is to be considered. It is affordable, non-invasive and relatively simple to perform and is the only method capable of assessing the deep system, as well as giving accurate information on the exact anatomy of the venous incompetence. The most recent guidance issued from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that ultrasound be used routinely in this setting.

Treatment

While evidently a concern, most patients with uncomplicated varicose veins will actually never progress to develop skin changes, ulceration or deep vein thrombosis and they can be confidently reassured that no intervention is necessary. NICE advises that patients should be referred to a vascular service if they have symptomatic varicose veins, skin changes, thrombophlebitis or a history of venous ulceration. For those in whom truncal reflux is confirmed, endothermal ablation with phlebectomies should be offered as a first-line treatment, provided the patient (and their venous anatomy) is suitable.

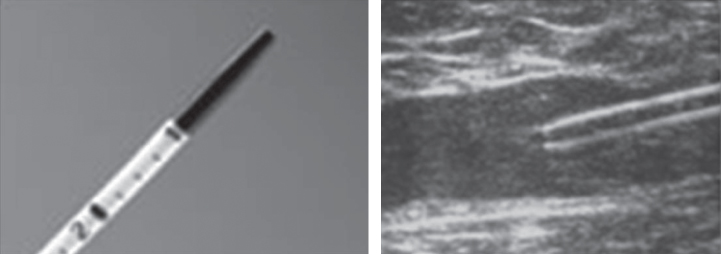

Radiofrequency and endovenous laser ablation techniques are similar in that both deliver energy directly to the lumen of the vein via an intravenous catheter placed percutaneously under ultrasound guidance (Figure 9.8). The energy causes destruction of the vein wall with the aim of generating fibrotic occlusion of the refluxing trunk and its consequent exclusion from the venous system. The advantages of these techniques are that they are performed under local rather than general anaesthetic, as day-case procedures. They are particularly attractive for recurrent varicose veins as they avoid the necessity for difficult redo groin dissection. Adverse tortuosity of the superficial veins is a relative contraindication as this tends to preclude satisfactory passage of the ablating catheter. Where veins lie particularly superficially, the overlying skin is at risk of thermal injury—a judgement must be made as to whether ablation is safe.

Figure 9.8 EVLT (endovenous laser treatment) catheter tip. The duplex image shows the catheter within the long saphenous vein.

If the patient is not suitable for endothermal ablation, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy should be offered. This technique is also performed on a day-case basis without general anaesthesia and, like the ablation techniques, does not mandate the utilisation of a formal operating theatre environment. Sclerotherapy involves infusion of a foamed sclerosant into a collapsed vein with the effect of causing apposition long enough for occlusive fibrosis to occur; however, it can lead to skin pigmentation (Figure 9.9). The advantage of using a foamed sclerosant is that it effectively displaces the blood from the vessel and can be easily seen with ultrasound.

Figure 9.9 One of the complications of injection sclerotherapy is brown skin pigmentation (arrows).

NICE guidance recommends that surgery be reserved for those individuals for whom the less invasive techniques are unsuitable. Surgery aims to treat the source of the venous incompetence, whether this is at the saphenofemoral vein junction, saphenopopliteal vein junction, at a perforator or through a recurrence. While open surgery can usually be performed as a day-case, it almost always necessitates a general anaesthetic and a formal theatre facility.

Compression hosiery may have a place in the management of varicose veins but in fact evidence for its benefit is weak. Therapy may relieve symptoms and prevent progression of skin changes, but stockings tend to be poorly tolerated (and subsequently irregularly applied) and they have to be worn indefinitely. As a result, NICE recommends that compression hosiery be reserved for those patients in whom other intervention is unsuitable.

Each of the invasive options carries the risk of recurrence and also of deep vein thrombosis, the latent incidence of which is probably slightly higher than the very small clinically manifest rate. In an attempt to reduce the thromboembolic risk of intervention, many surgeons administer heparin or low molecular weight heparin peri-operatively and some also advise patients taking hormone supplements to cease these around the time of treatment.

There remains a relative paucity of randomised and long-term outcome data for the non-surgical procedures but there is mounting evidence to support the assertion that their efficacy is likely to be at least similar to that of the traditional open surgical techniques.

Treatment of complications

Thrombophlebitis is a sterile inflammation, and, therefore, there is no indication for treatment with antibiotics. Instead, treatment consists of anti-inflammatories (systemic or topical) and analgesia. While compression is theoretically useful to reduce thrombus propagation, the reality is that this is often intolerable for an already painful leg. Referral to a vascular specialist is warranted, as intervention is frequently required for the abnormal vein in order to prevent recurrent episodes of inflammation. It is of particular concern when the thrombophlebitis tracks along the long saphenous vein in the thigh, as there is a risk of propagation of the thrombus across the saphenofemoral vein junction and into the deep system. This can usually be determined with duplex ultrasonography and should be treated with formal anticoagulation just as for a deep vein thrombosis. In addition, some surgeons advocate urgent operative disconnection and ligation of the saphenofemoral vein junction with extraction of the propagating thrombus under temporary deep venous control.

Haemorrhage from varicose veins is alarming for the patient and can on occasion be significant. It is usually easily remediable acutely with elevation of the leg and direct pressure on the bleeding point. A vascular surgeon should see the patient, with a view to treating the underlying venous abnormality.

Patients with ulceration or skin changes should undergo colour duplex ultrasound assessment to define the venous abnormality. Pure superficial reflux should generally be treated, but in the presence of deep venous incompetence, ablating the superficial veins will not improve the skin. In this situation, the mainstay of treatment is compression therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree