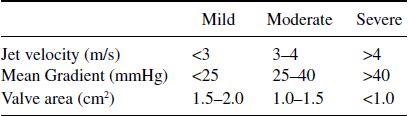

Table 24.1 Aortic Stenosis Severity.

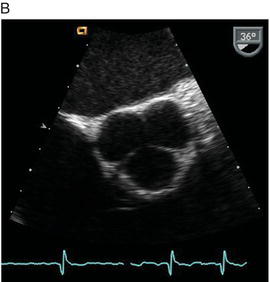

Figure 24.2 Echocardiographic images of a bicuspid aortic valve. A shows a bicuspid valve in systole; B shows a bicuspid valve in diastole.

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend transthoracic echocardiography for re-evaluation of asymptomatic patients every year for severe AS; every 1–2 years for moderate AS; and every 3–5 years for mild AS.

Calcific degeneration of an aortic valve (or senile calcification) is the most common cause of aortic stenosis and subsequent valve surgery. The disease tends to be progressive with an average decrease in valve area of 0.1 cm2 per year. Although the presence of aortic stenosis is associated with similar risk factors that exist for atherosclerosis (diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, male sex, and age), there is currently no compelling data to support risk factor modification as a treatment for aortic stenosis. When the aortic valve becomes heavily calcified, it can be difficult to differentiate a bicuspid from a tricuspid valve.

Bicuspid aortic valves affect approximately 2% of the population. It is more common in men than women, with a 3:1 ratio. Compared to patients born with a tricuspid valve, patients with a bicuspid aortic valve tend to develop aortic stenosis and insufficiency at an earlier age. In addition, a bicuspid aortic valve is associated with ascending aortic aneurysm and increased risk for dissection. Figure 24.2 demonstrates a short axis of a bicuspid valve. In this view, the valve opens freely without stenosis in an oval shape.

Rheumatic aortic valve stenosis is almost always associated with concurrent rheumatic mitral valve disease. In contrast to senile calcific aortic stenosis, in which calcification extends from the cusp bases, rheumatic disease initially affects the commissural edges and usually progresses gradually over several years.

24.2.2 Low Gradient Aortic Stenosis

Patients with left ventricular dysfunction may have severe aortic stenosis, but measured pressure gradients across the valve can be low due to a “low flow” state. In this situation, the clinician needs to differentiate “true stenosis” from “pseudostenosis.” True stenosis refers to an aortic valve with a hemodynamically significant mechanical obstruction with secondary left ventricular dysfunction. Pseudostenosis refers to an aortic valve with limited mobility that is secondary to low cardiac output from the left ventricle, not intrinsic valve disease. Dobutamine stress echocardiography can help distinguish between both conditions. In true stenosis, valve gradients increase with increased cardiac output without a change in aortic valve area. In pseudostenosis, the aortic valve area increases with increased cardiac output and valve gradients are unchanged. Cardiology consultation should be utilized to differentiate patients when low gradient aortic stenosis is suspected, since these patients will benefit from surgery.

24.2.3 Management of Aortic Stenosis

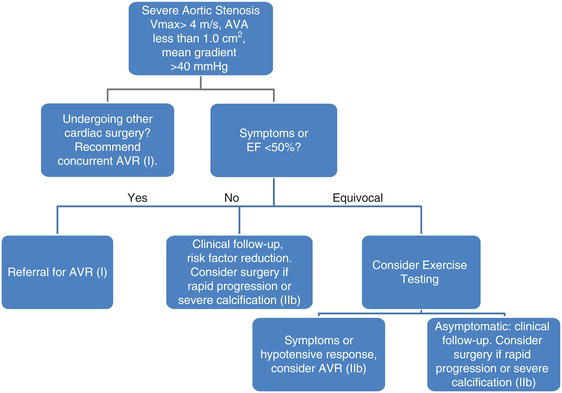

Appropriate patients with severe aortic stenosis and symptoms should undergo aortic valve replacement (Figure 24.3). However, symptom onset can be insidious with slowly progressive disease, and patients often compensate by decreasing activity. Once symptoms develop in the setting of severe aortic stenosis, the prognosis without surgery is very poor. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty can be considered as a palliative intervention, but restenosis rates at six months are high and long-term outcomes are inferior to surgery. Early clinical trials have suggested a role for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) implanted via percutaneous or transapical access in patients who are poor candidates for sugery.

Medical therapy is limited in aortic stenosis. Diuretics are helpful with fluid overload. Treatment of concurrent cardiac disease should be done with caution as afterload-reducing and preload-reducing medications can precipitate hypotension.

24.2.4 Aortic Regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation is a complex disease that varies broadly in its acuity of presentation, severity, etiology, and management. The most common causes of aortic valve regurgitation are listed in Table 24.2.

Figure 24.3 Algorithm for appropriate timing of aortic valve replacement (AVR) in aortic stenosis based on 2006 ACC/AHA guidelines. Per these guidelines, Class 1 recommendations “should be done,” Class IIa is “reasonable to perform,” and Class IIb “should be considered.”

Table 24.2 Causes of Aortic Insufficiency.

| Dilation of aorta Congenital valve abnormality (bicuspid) Calcific degeneration Rheumatic disease Infective endocarditis Aortic dissection |

Acute, severe aortic regurgitation can cause cardiovascular collapse due to a rapid increase in end-diastolic volume from regurgitant blood. The diastolic murmur associated with aortic regurgitation is low-pitched and early, and lessens with severity. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice. As a medical emergency, it should be treated in intensive care, with intravenous vasodilators, and with urgent surgical intervention in appropriate patients. An intra-aortic balloon pump is contraindicated and can worsen the severity of aortic regurgitation. It is important to rule out acute aortic pathology (dissection or aneurysm expansion) and endocarditis in acute aortic insufficiency since these are the most common causes.

Chronic aortic regurgitation, in contrast, is a slow and insidious disease process. Patients may frequently remain asymptomatic for several years due to the extensive compensatory mechanisms of the left ventricle that occur over time. Physical findings may be unreliable for grading the severity of chronic aortic regurgitation, but echocardiography is accurate at grading the severity of regurgitation as well as left ventricular function and size. Patients with symptomatic and severe chronic aortic regurgitation should be evaluated for aortic valve replacement. For asymptomatic patients with severe chronic aortic regurgitation, provoked symptoms on exercise testing, increased left ventricular size, and decreasing ejection fraction all are indications to pursue surgery. Figure 24.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree