Figure 12.1 – Areas of auscultation on examination.

12.1.1 Heart murmurs

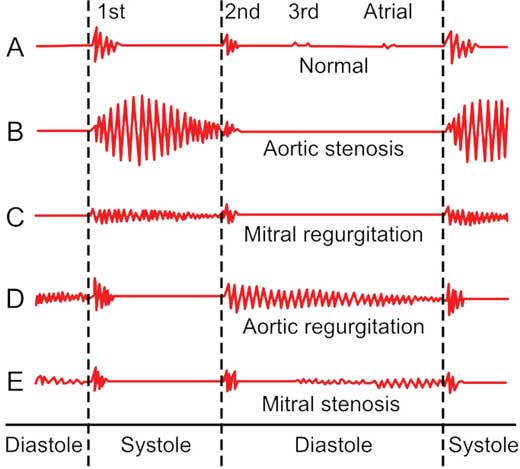

An appreciation of normal heart sounds is encouraged. One should familiarise oneself with the sounds of different murmurs, which may be subtle in clinical practice. Some experience is required to identify them correctly. It is also important to note that some murmurs are benign in nature.

Qualities of benign murmurs

- Soft

- Humming in nature

- Position-dependent: often disappear when sitting up

- Usually systolic; purely diastolic murmurs are always abnormal

- The patient is usually otherwise healthy

- Common in childhood.

Figure 12.2 – Illustration of heart murmurs in a cardiac cycle.

Respiratory effects

Respiratory manoeuvres can help differentiate between a similar right-sided and left-sided murmur (e.g. the pansystolic murmurs of tricuspid regurgitation and mitral regurgitation). All right-sided murmurs will increase on inspiration (Carvallo’s sign). Most left-sided murmurs are accentuated with held expiration, but this difference can be subtle.

Positional changes

Standing decreases venous return and therefore ventricular filling, which decreases the intensity of all murmurs except mitral valve prolapse and the systolic murmur associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular outflow obstruction.

Squatting increases peripheral resistance and ventricular filling. It enhances the murmurs of ventricular septal defects, aortic regurgitation and mitral regurgitation.

Sitting up and leaning forwards exaggerates the second heart sound and increases the murmur of aortic regurgitation. Tilting the body to the left increases the intensity of mitral murmurs, with the mid-diastolic murmur of mitral stenosis being affected on held expiration in particular.

12.2 Left side of the heart: Mitral valve

12.2.1 Mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis In A Heartbeat

Epidemiology | 2 per 100 000. Peak age 40–50 years. Rare in developed countries. Women are more susceptible. |

Aetiology | Majority due to rheumatic fever. |

Clinical features | Dyspnoea, fatigue. Strong association with AF. |

Investigations | Echo diagnostic, ECG, CXR |

Management | Anticoagulation if in AF or previous embolic events |

Definition

Mitral stenosis refers to narrowing of the mitral valve orifice that occurs as a result of fusion of the leaflet commissures.

Epidemiology

- 2 per 100 000

- Peak incidence is 40 to 50 years old

- Rare in developed nations, higher in developing world (proportional to rheumatic fever)

- Women are three times more likely to develop mitral stenosis from rheumatic fever than men.

Aetiology

Common causes:

- Rheumatic heart disease: most common cause (up to 95%). The carditis of rheumatic fever causes post-inflammatory changes to the mitral valve, but this can take many years to manifest (refer to Chapter 6).

Other causes:

- Ageing: degenerative calcification of the leaflets

- Congenital valve deformity: particularly in young adults with mitral stenosis

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Rheumatological disorders: rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus can both cause a valvulitis

- Amyloidosis: amyloid deposition on the mitral valves.

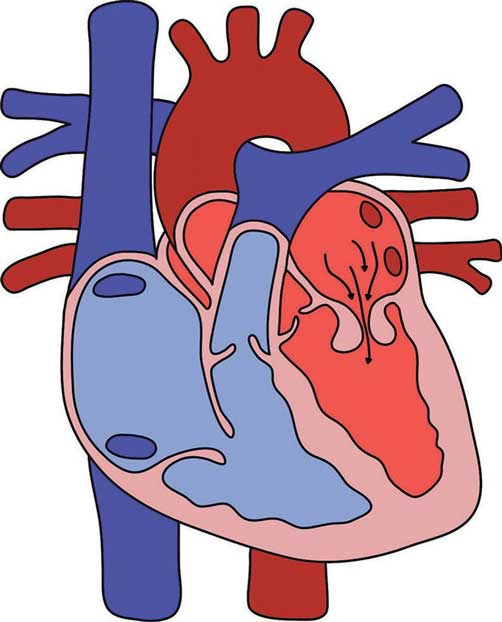

Pathophysiology

- Recurrent inflammation causes valve damage over time

- As the valve narrows as a result of damage, flow across the left atrium to the left ventricle is reduced

- This increases pressure in the left atrium, eventually leading to congestion of the pulmonary circulation due to backward transmission of said pressure

- Chronic congestion of blood in the left atrium causes left atrial dilatation which may lead to atrial fibrillation and can also predispose a patient to thromboembolism.

Figure 12.3 – Mitral valve stenosis.

// PRO-TIP //

Valve orifice area narrows from a normal 4–6 cm2 to a stenotic 2 cm2.

Clinical features

Key features

- Symptoms mimic those of left heart failure

- dyspnoea (pulmonary congestion and interstitial oedema)

- fatigue (low cardiac output state)

- dyspnoea (pulmonary congestion and interstitial oedema)

- Strong association with atrial fibrillation (47%)

- Haemoptysis

- Cor pulmonale: this is right heart failure resulting from pulmonary hypertension, often presenting with abdominal pain (hepatomegaly) and peripheral oedema.

// PRO-TIP //

Hoarseness and dysphagia can result from a large left atrium compressing the recurrent laryngeal nerve and oesophagus.

Examination findings

- Low-volume pulse (again as a result of decreased cardiac output)

- Mitral facies (flushed cheeks)

- Irregularly irregular pulse (AF)

- Tapping apex beat (strong and palpable first heart sound due to rigid mitral valve)

- On auscultation:

- loud first heart sound

- opening snap

- rumbling mid-diastolic murmur (accentuated when the patient leans to their left – refer to Chapter 2)

– pathognomonic of mitral stenosis.

- loud first heart sound

// Why? //

A loud first heart sound is due to an increase in the difference in pressure between the left atrium and left ventricle. This is often accompanied by an opening snap which is thought to occur because of the tension of the chordae tendineae and the stenotic valve leaflets.

// PRO-TIP //

A rumbling, mid-diastolic murmur is caused by turbulence across the valve as the left atrium contracts during diastole. The severity of the stenosis is directly related to the duration of the murmur because of the longer time required for the left atrium to empty.

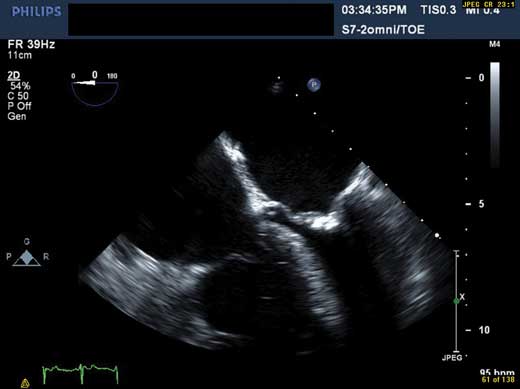

Investigations

First-line

1. Echocardiography (trans-thoracic echocardiogram)

- Recommended in all patients regardless of symptoms

2. ECG

- AF common

- P-mitrale (bifid P waves) due to left atrial enlargement

- May present with right axis deviation if chronic disease

3. CXR

- Left atrial enlargement: double shadow in right cardiac silhouette.

Figure 12.4 – Apical four-chamber view showing calcification in mitral stenosis.

Second-line

- Trans-oesophageal echocardiography – provides a more complete assessment of the valve.

Management

The principles of management are to provide symptomatic relief and prevent embolic events

- Anticoagulation

- warfarin should be given if in AF or previous embolic events

- atrial fibrillation should be treated (refer to Chapter 11)

- warfarin should be given if in AF or previous embolic events

- Symptomatic relief

- the onset of symptoms necessitates surgery. If this is not viable then medical therapy may be considered.

- diuretics: reduce dyspnoea and right heart failure

- beta-blockers: reduce heart rate and optimise cardiac output. They improve symptoms and exercise tolerance.

- the onset of symptoms necessitates surgery. If this is not viable then medical therapy may be considered.

- Valve intervention

- the only method of altering the natural history of the disease and improving survival

- indicated in the following:

– symptomatic severe mitral stenosis

– asymptomatic very severe mitral stenosis

– pulmonary hypertension

- several options include:

– percutaneous mitral balloon commissurotomy (PMBC) is first-line

– surgical repair, commissurotomy or valve replacement if PMBC fails or is unsuitable.

- the only method of altering the natural history of the disease and improving survival

Prognosis

- Mitral stenosis patients with minimal symptoms have a survival rate of more than 80%

- Proper use of anticoagulation and effective mechanical intervention confer an excellent prognosis

- Advanced symptoms or pulmonary hypertension reduce average survival to approximately three years.

12.2.2 Mitral regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation In A Heartbeat

Epidemiology | Prevalence greater than 5 million worldwide |

Aetiology | Acute – mitral valve prolapse, ischaemic papillary muscle dysfunction/rupture |

Clinical features | Acute – dyspnoea, features of pulmonary oedema |

Investigations | Echo gold standard, ECG, CXR |

Management | Do not delay until irreversible damage has occurred |

Definition

Mitral regurgitation refers to backflow of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium as a result of a leaky mitral valve.

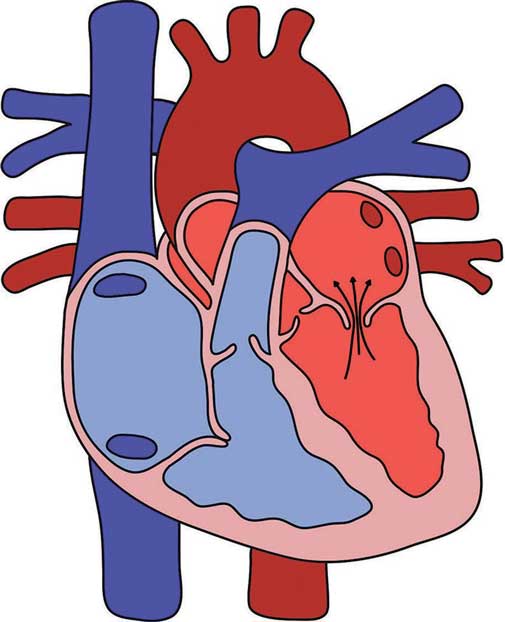

Figure 12.5 – Mitral valve regurgitation.

Aetiology

- Any aberrations to the mitral valve apparatus

- Acute mitral regurgitation:

- papillary muscle infarction

- ruptured chordae tendineae

- acute rheumatic fever

- infective endocarditis

- trauma

- papillary muscle infarction

- Chronic mitral regurgitation:

- primary mitral regurgitation (valve problems):

– mitral valve prolapse (Barlow’s syndrome) – most common cause in developed countries

– rheumatic heart disease – developing countries

– mitral valve calcification

– congenital anomalies

– connective tissue disease (e.g. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome)

- secondary mitral regurgitation

– this is where left ventricular remodelling or dilatation distorts the valvular apparatus

– coronary heart disease: ischaemic mitral regurgitation

– left ventricular dilatation: cardiomyopathy.

- primary mitral regurgitation (valve problems):

Epidemiology

- Prevalence greater than 5 million worldwide

- Exact numbers are unknown.

Pathophysiology

Backflow into the left atrium causes a decrease in cardiac output. This results in an increase in left atrial pressure and left atrial dilatation over time, as well as volume loading of the left ventricle. Ventricular filling increases in the subsequent systole as regurgitant blood flows back to the left ventricle.

In acute mitral regurgitation of native valves, a lack of physiological compensation means that increased left atrial pressure results in significant haemodynamic instability and pulmonary oedema. This can be life-threatening.

In chronic mitral regurgitation, compensatory mechanisms occur. This leads to a decrease in cardiac output over time, as left ventricular dysfunction ensues secondary to eventual volume overload.

Clinical features

Key features

Acute mitral regurgitation

- Presents as an emergency

- Sudden onset severe dyspnoea

- Rapidly progressive pulmonary oedema

- Hypotension and cardiogenic shock

Chronic mitral regurgitation

- Asymptomatic if mild or moderate

- Symptoms occur when left heart failure develops in severe mitral regurgitation

- dyspnoea on exertion

- fatigue

- dyspnoea on exertion

- Atrial fibrillation

- At risk of developing infective endocarditis

Examination findings

- Atrial fibrillation

- Displaced apex beat

- On auscultation:

- third heart sound may be heard (due to increased volume in the left ventricle)

- blowing pansystolic murmur radiating to axilla (best heard at the apex).

- third heart sound may be heard (due to increased volume in the left ventricle)

// Why? //

The murmur of mitral regurgitation is pansystolic (i.e. it occurs throughout systole) because the murmur starts as soon as the ventricle contracts. Blood flow through the valve may continue even after the second heart sound as the pressure difference between the left atrium and left ventricle continues. There is radiation to the axilla as turbulent blood flow proceeds in that direction. This is also why dynamic movements can help accentuate the murmur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree