The normal aortic valve orifice area (AVA) is 3 to 4 cm2; clinically significant gradients occur when AVA is reduced by one half, and symptoms usually arise when AVA is one fourth of normal size.

Gradients are less predictive (a mean gradient > 50 mm Hg has >90% positive predictive value for severe AS, but there is no clear cutoff for a good negative predictive value3).

Most common etiologies: Congenital, rheumatic, and calcific (degenerative) (See Table 12-2.)

Under 70 years: >50% congenital; over 70 years: ˜ 50% degenerative4

Pressure gradient between the left ventricle (LV) and aorta (increased afterload)

Initially, cardiac output is maintained through compensatory mechanisms of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), increased preload, and increased myocardial contractility.

If preload reserve is exceeded or if LV function declines, cardiac output fails to increase (fixed cardiac output).

Cardinal manifestations: Classic triad of angina, exertional syncope, and congestive heart failure (CHF).

Angina is due to increased myocardial demand/decreased coronary flow reserve.6

Syncope can be due to exercise-related vasodilation in the setting of fixed cardiac output,7 as well as a vasodepressor response.8

CHF results from diastolic dysfunction, systolic dysfunction, or both.

TABLE 12-1 Grading of severity of AS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 12-2 Etiology of AS | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Progression of AS is poorly understood; the latent phase is prolonged.

Rate of progression

– Mild AS to severe AS: 8% in 10 years, 22% in 20 years, and 38% in 25 years11

– Decrease in valve area of 0.1 to 0.3 cm2/year and increase in peak pressure gradient of 10 to 15 mm Hg/year12, 13, and 14

– Faster progression in calcific AS than in congenital malformations15

The onset of symptoms marks an important transition with a marked decline in survival (50% survival over 2, 3, and 5 years for patients with CHF, syncope, and exertional angina, respectively).16

Presence of symptoms may be difficult to gauge, especially in sedentary/elderly individuals.

Systolic ejection murmur is heard best in the aortic area/apex radiating to neck and right clavicle.

Gallavardin phenomenon (disappearance of the murmur over the sternum and reappearance over the apex, mimicking mitral regurgitation (MR))

Intensity of murmur does not accurately reflect severity of stenosis.

Later peaking murmur is associated with worsening severity of stenosis.

S2 is absent, single, paradoxically split in severe AS.

Pulsus parvus et tardus (slow rising arterial pulse with reduced peak) in severe AS

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) may be useful in differentiating symptomatic from asymptomatic patients (BNP >66 pg/mL has predictive accuracy of 84% for symptomatic AS).17,18

Chest x-ray can show dilated proximal ascending aorta (poststenotic dilatation) and calcification of cusps on lateral films.

Electrocardiogram

– Usually normal sinus rhythms (NSR), but AF is common in elderly AS patients

– Complete heart block may occur in calcific AS

– Left atrial enlargement present in 80% of patients

– LVH with secondary ST-T changes

Echo

– Useful for diagnosis, determining severity (AVA, velocity, gradient; see Table 12-1)

– AVA is determined using the continuity equation (conservation of mass).

– Peak pressure gradient is determined using Continuous Wave (CW) Doppler.

Recommendations for serial studies (in the absence of symptoms)1

Mild: Every 5 years

Moderate: Every 2 years

Severe: Every 6 months to 1 year

Contraindicated in symptomatic patients

Should be considered in patients severe AS, with unclear symptom status

Guidelines recommend consideration for surgery in asymptomatic patients with abnormal response to exercise (symptoms, <20 mm Hg increase in BP, ST depression, and/or complex ventricular arrhythmias).21

Employed in patients with AS, depressed LVEF with two primary goals

DSE can help distinguish severe stenosis from pseudo (flow dependent) AS.22

DSE can help to identify patients with pre-operative cardiac reserve (increase in stroke volume by >20%, or in mean transvalvular gradient of 10 mm Hg) as this subset of patients with low EF tends to have better outcomes (surgical mortality of 6% vs. 33%).23

Catheterization is used to assess coronary anatomy (prior to surgery).

Catheterization used to confirm/clarify diagnosis, severity by determining transvalvular gradient (simultaneous aortic, LV pressures are most accurate) and calculation of AVA by Gorlin formula or Hakki formula.

The gradient is dependent on transvalvular flow, so errors occur in patients with low cardiac output.

Dobutamine can be used to distinguish pseudostenosis from true anatomically severe AS.

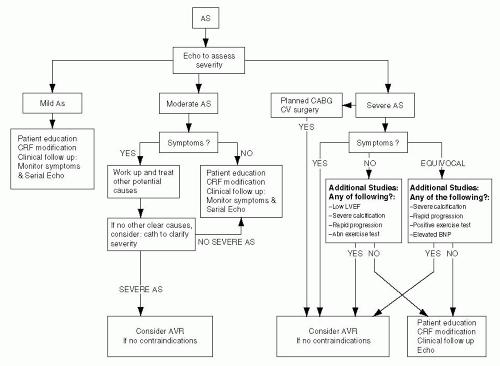

Identify patients that warrant surgery with close monitoring for onset of symptoms.

Medical therapy has a limited role in providing a survival benefit or slowing progression.

Symptomatic severe AS should be referred for surgery: Mortality high without surgery16; age-corrected survival after surgery is near normal.24

Patients with asymptomatic severe AS generally have a good prognosis,25 but there is a risk of sudden death (˜ 2%) and of irreversible myocardial damage.25,26

Identify subset of asymptomatic severe AS patients at risk for SCD and/or onset symptoms that would require surgery in the near future.

Patients at highest risk for symptom onset/needing surgery in the short term include: Peak aortic velocity >4m/s;24 Severe calcification of the aortic valve;10 Rapid progression of aortic velocity (increase of >0.3 m/s per year).10

Exercise testing: A negative test has a strong negative predictive value (85%-87%) for event-free survival20 but is positively predictive (79%) only in physically active patients <70 years old.21

No randomized controlled data support the strategy of referring “high-risk” patients with asymptomatic severe AS for AVR, but this is a Class II recommendation (see Table 12-3).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated if high risk for endocarditis (see Chapter 13).26

Afterload agents are considered to be contraindicated because of concern over hemodynamic collapse (supporting data is lacking).

Considered to be contraindicated because of concern over hemodynamic collapse (supporting data is lacking)

Afterload reducing agents have been shown to be beneficial in patients with severe AS and bw EF27 and decompensated CHF.28

ACE inhibitors are well tolerated.29

Data on the role of statins in slowing progression of AS is conflicting.

A single randomized controlled trial showed no effect of statins on progression of AS.36

Several randomized controlled trials of statins in AS are pending.

TABLE 12-3 Indications for AVR in AS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AVR is the only effective treatment for symptomatic AS.

Symptoms/high risk features are the chief indications for AVR.

Operative mortality for AVR ˜5% to 30% depending on the patient population

Predictors of higher operative mortality and lower late survival: CHF, low LVEF, chronic kidney disease, urgent procedures, and need for concomitant CABG or MVR39

Outcomes similar in patients with preserved LV function and with moderate LV dysfunction

Provocative testing (DSE) can identify patients with contractile reserve; this subgroup may have better surgical outcomes.23

Surgical mortality is very high (30%-50%) in patients with severe AS and decompensated heart failure who are taken directly to surgery42 (balloon valvuloplasty and medical optimization are important bridge therapies).

In patients with severe AS who need surgical intervention, but are poor candidates, percutaneous AVR may represent a safe, viable alternative.43

Aortic regurgitation (AR) is due to ineffective coaptation of aortic cusps.

The prevalence of chronic AR increases with age; the majority of patients with AR have trace or mild AR.44

Grading of severity is based on several qualitative and/or quantitative measures. (See Table 12-4.)

AR can be due to primary valvular disease and/or aortic pathology (see Table 12-5).

AR can be acute or chronic, and the clinical presentation of each entity is distinct.

Chronic AR is more common than acute AR.

Acute AR is commonly caused by endocarditis, aortic dissection, and trauma.

Chronic AR is usually due to degenerative, aortic root, congenital abnormalities.

Large regurgitant volume into a nondilated LV leads to an abrupt increase in LV end diastolic pressure (LVEDP).

Compensatory tachycardia usually insufficient to maintain cardiac output

Poor hemodynamic tolerance: LVEDP equalizes with diastolic aortic pressure with subsequent pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock.

TABLE 12-4 Grading of severity of AR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 12-5 Etiology of AR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Combined volume and pressure overload on the LV

Volume overload due to regurgitant volume

Pressure overload due to increased afterload (hypertension [HTN] from increased aortic stroke volume)

Three compensatory mechanisms initially preserve cardiac output: Increased LV end diastolic volume; increased chamber compliance; LVH (eccentric/concentric).

Compensated phase can last for years/decades.

Eventually, progressive LV dilation and LV systolic dysfunction lead to CHF.

Patients with acute AR present with marked dyspnea and pulmonary edema.

Patients with chronic AR can be asymptomatic for many years.

Angina without structural coronary artery disease is due to decreased coronary perfusion (due to high LVEDP).

Exertional dyspnea is the most common presenting symptom in chronic AR (late stage).

Syncope and sudden cardiac death are rare in absence of other symptoms.

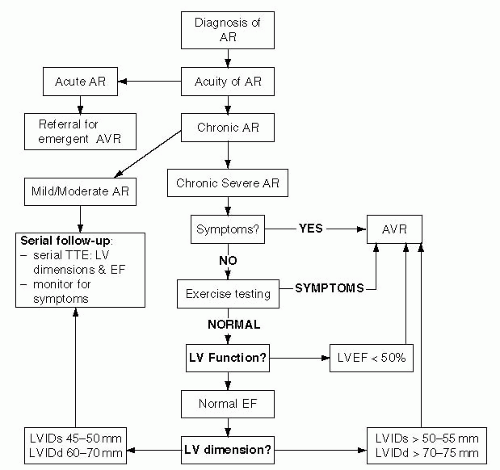

Progression of AR results from complex interplay of multiple variables.

Mild AR: Minimal data on natural history; Most patients with mild AR probably do not progress to severe AR.

Moderate to severe AR

Asymptomatic patients with normal systolic function

– Predictors of progression: Age, LV dimensions at end systole (LVIDs) and LV dimension at end diastole (LVIDd), and LVEF during exercise46,47,48,49, 50, and 51

– Unlike AS, onset of symptoms is not the only important factor

Asymptomatic patients with systolic dysfunction

– Majority will need AVR in 2 to 3 years

Symptomatic patients

– No contemporary studies, but outcomes are poor with medical therapy

The high-frequency decrescendo blowing diastolic murmur is heard best over the left lower sternal border (LLSB) through stethoscope’s diaphragm with patient sitting upright during forced expiration.

Murmurs that are louder over right lower scapular border (RLSB) are more likely due to aortic root/ascending aorta pathology, rather than primary valve abnormalities.

Duration of murmur correlates with severity (mild AR – short murmur; severe AR – typically holodiastolic).

In acute AR, the diastolic murmur and peripheral signs (see Table 12-6) may be absent (the only clue may be absent S2 with hypotension/pulmonary edema).

Austin Flint murmur (mid-late diastolic rumble that resembles MS – due to vibration from AR jet striking the mitral valve)

Pulse: High-amplitude, rapidly collapsing pulse (waterhammer pulse)

Chest x-ray can be normal or demonstrate pulmonary edema, cardiomegaly, or dilated aorta.

ECG shows LAD, LVH and signs of LV diastolic volume overload (high QRS amplitude and tall T waves with ST depression), and conduction abnormalities.

Assessment of anatomy of aortic leaflets, aortic root, LV size/function, and severity of AR

Estimation of severity is based on color flow and Doppler parameters (Table 12-4)

Supportive findings:

– Early mitral valve closure by M-Mode (can be masked by tachycardia)

– AR pressure half time: Mild >500 milliseconds and severe <200 milliseconds (confounded by filling volumes and diastolic function)

– Holodiastolic flow reversal in descending aorta reflective of at least moderately severe AR

Recommendations for serial studies in asymptomatic patients

– Mild AR and normal LV size and function: Every 2 to 3 years

– Patients with LV dilation: Every 6 to 12 months

– Patients with advanced LV dilation (LVIDs >50 mm, LVIDd >70 mm): Risk of progression 10%-20%/year;46 studies every 4-6 mos.

– Associated aortic root disease: Monitoring of aortic root size

TABLE 12-6 Auscultatory and peripheral findings in severe AR: A glossary of eponyms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree