Although it is well known that certain characteristics, such as older age, female gender, hypertension, and high body mass index, are closely associated with severe arterial tortuosity among patients undergoing transradial coronary angiography, few data are available regarding useful predictors of severe arterial tortuosity among geriatric patients. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the characteristics of geriatric patients with severe tortuosity of the right subclavian artery or brachiocephalic artery. The coronary angiographic reports of patients with severe tortuosity of the right subclavian artery or brachiocephalic artery and age- and gender-matched control patients were retrospectively evaluated. A total of 847 consecutive patients underwent right transradial coronary angiography. Of these patients, 48 (5.7%) had severe tortuosity (29 women, age 73.4 ± 8.6 years). The factors associated with severe arterial tortuosity were greater body mass index (odds ratio 1.17, p = 0.02), the presence of a prominently projected aortic arch on a chest radiograph (odds ratio 5.62, p <0.01), and lower serum creatinine value (odds ratio 0.05, p <0.01). In conclusion, the presence of a prominently projected aortic arch on the chest radiograph is a useful predictor of severe arterial tortuosity.

The transradial approach for coronary angiography (CAG) has gained popularity, because it results in no major ischemic complications in cases of occlusion in patients with normal Allen test findings, better patient comfort, and no need for bed rest after the procedure. The right radial artery is commonly used because most catheterization laboratories are set up for a right-sided patient approach. With the super aging of society such as in Japan, the number of geriatric patients undergoing CAG is expected to increase. It is well known that older age, female gender, hypertension, and a high body mass index (BMI) are closely associated with severe tortuosity of the right subclavian artery (RSA). However, for geriatric patients in particular, few data are available regarding the useful predictors for severe arterial tortuosity. We hypothesized that the presence of a prominently projected aortic arch on a chest radiograph is a useful predictor of severe arterial tortuosity.

Methods

Consecutive patients who underwent right transradial CAG with severe tortuosity of the RSA or brachiocephalic artery (BCA) were retrospectively evaluated. Age- and gender-matched control patients who underwent right transradial CAG without tortuosity of the RSA or BCA were also evaluated. All patients and control subjects were identified by a review of all coronary angiographic reports from July 2003 to August 2011. The patients were excluded if they were receiving hemodialysis, needed repeat examinations with the right radial artery approach, or required an alternative arterial access because of failure of right radial artery puncture or the presence of significant stenosis of the right radial artery. All patients provided written informed consent to undergo CAG. The institutional ethics committee of Juntendo Tokyo Koto Geriatic Medical Center approved the study.

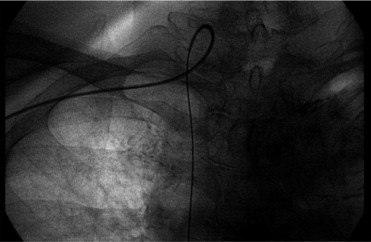

Because there is no clear definition of severe tortuosity of the RSA and BCA, severe tortuosity of the RSA or BCA was arbitrarily defined as major difficulty in passing the tortuous RSA or BCA using a flexible hydrophilic guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) to support the catheter and complete angiography ( Figure 1 ) or the need for alternative arterial access because of the tortuous RSA or BCA. All cases of severe tortuosity of the RSA or BCA were recorded in the coronary angiographic reports.

The baseline characteristics and clinical data of the patients were collected from the medical records, which were reviewed by experienced cardiologists. The cardiovascular risk factors, including smoking habit, systemic hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and family history of cardiovascular disease, were assessed. The smoking habit was divided into 3 categories: current, former, and never smoker. A former smoker was defined as previous smoking (>2 pack-years). Systemic hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or medically treated. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥220 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥140 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≤40 mg/dl, fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl, or medically treated. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl, postprandial blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl, or medically treated. Weight, height, BMI, and body surface area were also assessed. The BMI was defined as the body weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m). The body surface area was calculated from the body weight and height using the Du Bois formula: body surface area (m 2 ) = 0.007184 × height 0.725 × body weight 0.425 . The patients were also evaluated for concurrent atrial fibrillation, dementia, a history of malignancy, stroke, and the use of medications (statins, antiplatelet agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, β blockers, warfarin, and diuretics). The clinical indications for CAG were also assessed using 4 categories: stable angina pectoris, acute coronary syndrome, atypical chest pain, and other.

The echocardiographic examination was performed using a commercially available echocardiographic machine (Sonos 5500, Philips, Bothell, WA). Almost all patients underwent a comprehensive examination that included 2-dimensionaland Doppler echocardiography by an experienced sonographer or cardiologist before CAG. The interventricular septal wall thickness, posterior wall thickness, left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic dimension, LV end-systolic dimension, LV mass index, relative wall thickness, LV ejection fraction, presence of asynergy, early diastolic filling wave/atrial filling wave ratio (E wave/A wave ratio), left atrial dimension, aortic valve annulus dimension, and aortic valve peak velocity were evaluated. The LV end-diastolic volume and LV end-systolic volume were measured by the disk method using 2-dimensional images obtained from the apical 4- and 2-chamber views. The LV ejection fraction was calculated using the following equation: 100 × (end-diastolic volume − end-systolic volume)/end-diastolic volume. The LV mass index was calculated using the formula recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography: LV mass index (g/m 2 ) = (1.04 [(interventricular septal wall thickness + LV internal diameter + posterior wall thickness) ] − 14 g)/body surface area. The relative wall thickness was calculated using the following formula: [(posterior wall thickness + interventricular septal wall thickness)/LV end-diastolic dimension]. Almost all patients underwent ankle-brachial index and pulsewave velocity testing. All patients underwent electrocardiography before CAG. Lower ankle-brachial index and greater pulsewave velocity values and the electrocardiographic voltage were evaluated. The electrocardiographic voltage was calculated using S1 plus R5. The following laboratory data were assessed: hemoglobin, red blood cell distribution width, creatinine, hemoglobin A1c, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein ratio, triglycerides, and brain natriuretic peptide.

CAG using the right radial artery approach was performed with standard Judkins techniques with a flexible hydrophilic guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) or multipurpose catheter technique in all patients. The results of CAG, including the presence or absence of severe tortuosity of the RSA or BCA, were reported by the most experienced cardiologist in the institution. The severity of coronary stenosis was visually determined and is expressed as the percentage of luminal diameter. Stenosis was considered significant if it was >75% according to the American Heart Association guideline. The presence or absence of significant lesions, double-vessel disease, triple-vessel disease, and left main coronary trunk lesions was evaluated.

All patients underwent chest radiography (posteroanterior view) before CAG. The cardiothoracic ratio, presence or absence of a prominently projected aortic arch, and presence or absence of aortic arch calcification were evaluated. Because there is no clear definition of a prominently projected aortic arch on the chest radiograph, the presence of a prominently projected aortic arch was arbitrarily defined as the distance from the neck of the aortic arch to the left edge of the aortic arch of ≥10 mm. This definition of a prominently projected aortic arch is shown in Figure 2 .

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or as numbers and ratios (%). Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired t test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Significant variables related to severe tortuosity of the RSA or BCA were determined using a multivariate logistic regression model. Variables with a p value <0.10 on univariate analysis were also entered in the multivariate logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05.

Results

The total number of consecutive patients who underwent CAG with the right radial artery approach was 860, and the number of patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was 847. All patient characteristics are listed in Table 1 . When the prominently projected aortic arch on the chest radiograph was categorized, the odds ratio for the presence of severe tortuosity of the RSA or BCA was 5.62 for patients whose distance from the neck of the aortic arch to the left edge of the aortic arch was ≥10 mm (n = 26) compared with a distance of <10 mm (n = 21) and 5.39 in patients whose distance was ≥15 mm (n = 9) compared with a distance of <15 mm (n = 38). Two patients (1.4%) were difficult to evaluate in the present study. One patient had a prominent pulmonary artery ( Figure 3 ) . The second patient had previously undergone thoracoplasty ( Figure 4 ) . The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis are listed in Table 2 . The body weight (p = 0.08) was not entered in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, because the body weight shows a close correlation with BMI.

| Variable | Severe Tortuosity | All Patients (n = 144) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 48) | No (n = 96) | |||

| Age (years) | 73.4 ± 8.6 | 73.2 ± 8.6 | 73.2 ± 8.6 | 0.90 |

| Men | 19 (39.6%) | 38 (39.6%) | 57 (39.6%) | 1.00 |

| Height (cm) | 153.0 ± 8.7 | 155.0 ± 9.5 | 154.3 ± 9.3 | 0.21 |

| Weight (kg) (n = 143) | 60.6 ± 10.4 | 57.4 ± 10.2 | 58.4 ± 10.4 | 0.08 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) (n = 143) | 26.0 ± 4.6 | 23.9 ± 3.1 | 24.6 ± 3.8 | <0.01 ⁎ |

| Body surface area (m 2 ) (n = 143) | 1.57 ± 0.15 | 1.55 ± 0.17 | 1.56 ± 0.16 | 0.49 |

| Hypertension | 37 (77.1%) | 72 (75.0%) | 109 (75.7%) | 0.78 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (31.2%) | 42 (43.8%) | 57 (39.6%) | 0.15 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 25 (52.1%) | 50 (52.1%) | 75 (52.1%) | 1.00 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (10.4%) | 10 (10.4%) | 15 (10.4%) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 3 (6.3%) | 10 (10.4%) | 13 (9.0%) | 0.41 |

| Dementia | 5 (10.4%) | 4 (4.2%) | 9 (6.3%) | 0.14 |

| History of stroke | 7 (14.6%) | 12 (12.6%) | 19 (13.2%) | 0.75 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease | 16 (33.3%) | 22 (22.9%) | 38 (26.4%) | 0.18 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 7 (14.6%) | 7 (7.3%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.16 |

| Former smoker | 16 (33.3%) | 29 (30.2%) | 45 (31.3%) | 0.70 |

| Never smoker | 25 (52.1%) | 60 (62.5%) | 85 (59.0%) | 0.23 |

| Medication | ||||

| Statin | 15 (31.3%) | 38 (39.6%) | 53 (36.8%) | 0.33 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 29 (60.4%) | 57 (59.4%) | 86 (59.7%) | 0.90 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 5 (10.4%) | 6 (6.3%) | 11 (7.6%) | 0.37 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 21 (43.8%) | 41 (42.7%) | 62 (43.1%) | 0.91 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 29 (60.4%) | 50 (52.1%) | 79 (54.9%) | 0.34 |

| β Blocker | 7 (14.6%) | 14 (14.6%) | 21 (14.6%) | 1.00 |

| Warfarin | 2 (4.2%) | 6 (6.3%) | 8 (5.6%) | 0.61 |

| Diuretics | 6 (12.5%) | 20 (20.8%) | 26 (18.1%) | 0.22 |

| Stable angina pectoris | 34 (70.8%) | 59 (61.5%) | 93 (64.6%) | 0.27 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 4 (8.3%) | 10 (10.4%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.69 |

| Atypical chest pain | 9 (18.8%) | 23 (24.0%) | 32 (22.2%) | 0.48 |

| Other | 1 (2.1%) | 4 (4.2%) | 5 (3.5%) | 0.52 |

| Presence of a significant coronary lesion | 17 (35.4%) | 47 (49.0%) | 64 (44.4%) | 0.12 |

| Number of coronary arteries narrowed | ||||

| 2 | 5 (10.4%) | 17 (17.7%) | 22 (15.3%) | 0.25 |

| 3 | 2 (4.2%) | 8 (8.3%) | 10 (6.9%) | 0.35 |

| Left main | 0 | 3 (3.1%) | 3 (2.1%) | 0.22 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio (%) (n = 143) | 51.8 ± 5.5 | 50.3 ± 6.6 | 50.8 ± 6.3 | 0.20 |

| Presence of prominently projected aortic arch (n = 142) | 26 (55.3%) | 18 (19.0%) | 44 (31.0%) | <0.01 ⁎ |

| Presence of aortic arch calcium (n = 143) | 20 (41.7%) | 32 (33.7%) | 52 (36.4%) | 0.35 |

| Ventricular septal wall thickness (mm) (n = 141) | 10.3 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 0.60 |

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) (n = 141) | 10.3 ± 1.5 | 10.3 ± 1.6 | 10.3 ± 1.5 | 0.96 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (mm) (n = 141) | 46.1 ± 4.3 | 44.6 ± 5.5 | 45.1 ± 5.2 | 0.11 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic dimension (mm) (n = 141) | 26.7 ± 5.5 | 27.1 ± 6.5 | 27.0 ± 6.1 | 0.75 |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m 2 ) (n = 140) | 128.2 ± 42.4 | 126.2 ± 49.6 | 126.9 ± 47.2 | 0.81 |

| Relative wall thickness (n = 141) | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Ejection fraction (%) (n = 142) | 72.5 ± 9.9 | 69.2 ± 12.1 | 70.3 ± 11.5 | 0.10 |

| Presence of asynergy (n = 142) | 6 (12.5%) | 11 (11.7%) | 17 (12.0%) | 0.89 |

| E wave/A wave ratio (n = 119) | 0.80 ± 0.23 | 0.80 ± 0.27 | 0.80 ± 0.26 | 0.99 |

| Left atrial dimension (mm) (n = 139) | 38.1 ± 5.2 | 35.8 ± 5.4 | 36.5 ± 5.4 | 0.02 ⁎ |

| Aortic valve annulus dimension (mm) (n = 135) | 20.2 ± 2.5 | 19.7 ± 3.8 | 19.9 ± 3.5 | 0.50 |

| Aortic valve peak velocity (m/s) (n = 137) | 1.17 ± 0.86 | 1.02 ± 0.72 | 1.07 ± 0.77 | 0.31 |

| Ankle-brachial index (n = 124) | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 1.09 ± 0.15 | 1.09 ± 0.14 | 0.86 |

| Pulsewave velocity (cm/s) (n = 123) | 1,909 ± 469 | 1,911 ± 411 | 1,910 ± 427 | 0.98 |

| Electrocardiography: voltage [S1+R5] (mV) (n = 143) | 2.53 ± 0.84 | 2.52 ± 0.95 | 2.52 ± 0.91 | 0.92 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.2 ± 2.1 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 13.2 ± 1.9 | 0.81 |

| Red blood cell distribution width (%) | 14.7 ± 2.6 | 14.4 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 1.9 | 0.33 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.71 ± 0.21 | 0.88 ± 0.48 | 0.83 ± 0.42 | 0.02 ⁎ |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) (n = 137) | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 0.23 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) (n = 141) | 205 ± 36 | 202 ± 40 | 203 ± 39 | 0.63 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) (n = 139) | 121 ± 36 | 120 ± 33 | 121 ± 34 | 0.92 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) (n = 139) | 54 ± 15 | 52 ± 13 | 52 ± 14 | 0.44 |

| Low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein ratio (n = 139) | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 0.73 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) (n = 141) | 145 ± 72 | 137 ± 92 | 139 ± 86 | 0.62 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide (pg/dl) (n = 58) | 65.7 ± 72.5 | 98.8 ± 127.6 | 80.0 ± 100.4 | 0.22 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree