Patients sustaining an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) frequently develop pulmonary congestion or pulmonary edema (PED). We previously showed that lung impedance (LI) threshold decrease of 12% to 14% from baseline during admission for STEMI marks the onset of the transition zone from interstitial to alveolar edema and predicts evolution to PED with 98% probability. The aim of this study was to prove that pre-emptive LI-guided treatment may prevent PED and improve clinical outcomes. Five hundred sixty patients with STEMI and no signs of heart failure underwent LI monitoring for 84 ± 36 hours. Maximal LI decrease throughout monitoring did not exceed 12% in 347 patients who did not develop PED (group 1). In 213 patients LI reached the threshold level and, although still asymptomatic (Killip class I), these patients were then randomized to conventional (group 2, n = 142) or LI-guided (group 3, n = 71) pre-emptive therapy. In group 3, treatment was initiated at randomization (LI = −13.8 ± 0.6%). In contrast, conventionally treated patients (group 2) were treated only at onset of dyspnea occurring 4.1 ± 3.1 hours after randomization (LI = −25.8 ± 4.3%, p <0.001). All patients in group 2 but only 8 patients in group 3 (11%) developed Killip class II to IV PED (p <0.001). Unadjusted hospital mortality, length of stay, 1-year readmission rate, 6-year mortality, and new-onset heart failure occurred less in group 3 (p <0.001). Multivariate analysis adjusted for age, left ventricular ejection fraction, risk factors, peak creatine kinase, and admission creatinine and hemoglobin levels showed improved clinical outcome in group 3 (p <0.001). In conclusion, LI-guided pre-emptive therapy in patients with STEMI decreases the incidence of in-hospital PED and results in better short- and long-term outcomes.

The evolution of pulmonary congestion or pulmonary edema (PED) in the course of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is associated with higher mortality. Prevention of PED during AMI may improve prognosis; however, this concept has not yet been tested. Early signs of PED on physical examination are subtle and are not sufficiently sensitive to allow hemodynamic monitoring. A decrease in lung impedance (LI) reflects an increase in lung fluid content and may herald evolving PED and indicate the need to initiate pre-emptive therapy. We previously showed in patients with AMI that LI reflects lung fluid content and that a threshold LI decrease >12% from baseline marks the onset of the transition zone from interstitial to alveolar edema and accurately predicts evolution to PED. Likewise, experience with implantable impedance devices has shown that LI decreases nearly 8% to 13% during the asymptomatic interstitial stage of evolving PED. However, implanted devices are unavailable in the course of AMI, whereas existing noninvasive impedance devices are disadvantaged by their limited sensitivity to detect small LI changes occurring during the interstitial stage of PED. In this study we used a noninvasive device that is 50-fold more sensitive than current devices. The aim of this study was to prove that LI-guided pre-emptive therapy initiated at the asymptomatic stage of evolving PED (Killip class I) in patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) may prevent its progression to more advanced stages of PED (Killip classes II to IV) and thus result in better outcomes.

Methods

This randomized 2-center study included patients admitted to the coronary care unit for STEMI without signs of acute heart failure on admission, i.e., with no dyspnea, at Killip class I with a normal chest x-ray, and without previous heart failure. During hospitalization, repeated lung auscultations were done, and respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation were recorded every hour. Diagnosis of PED was based on chest x-rays and a modified Killip classification: class I, no dyspnea and no rales; class IIA, no dyspnea but detection of rales at the lung bases; class IIB, no dyspnea and rales over the lower 1/2 of the lung fields; class IIC, dyspnea and rales over the lower 1/2 of the lung fields; class III, dyspnea and rales over most or the entire lung fields; and class IV, cardiogenic shock. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board and the ministry of health ethics committee (HT3-657-1). Participants provided signed informed consent.

LI was monitored in this study using a noninvasive impedance device (RSMM Company, Tel Aviv, Israel) as described previously and measured in ohms but reported as percent change from initial measurement. Such an LI presentation with patients serving as their own controls is widely used and allows the assessment of changes in lung fluid content but not of the absolute value of lung fluid volume. An LI change of 1 Ω is usually equivalent to a 1.5% to 2.5% change from baseline value. Regular electrocardiographic electrodes were used for LI monitoring with measurements at 60-minute intervals. Chest x-ray was used to validate changes in lung fluid content. We formulated a radiologic score (RS) for quantitative assessment of roentgenologic signs of lung congestion. The RS was calculated as the sum of sign values and defined as follows: 0 to 1, no lung edema; 2 to 4, interstitial lung congestion; 5 to 6, mild alveolar edema; 7 to 8, moderate alveolar edema; and 9 to 10, severe alveolar edema.

Group 1 included all study patients whose maximal LI decrease during monitoring did not exceed 12%. The remaining patients were randomized on reaching the LI threshold decrease of 12% to 14% to a conventional treatment (group 2) or to pre-emptive LI-guided therapy (intervention group, group 3) at a 2:1 ratio. Study patients were treated for STEMI according to current guidelines. In group 2, initiation of treatment for PED was based on clinical assessment (patient report of dyspnea and 1 of the following: lung rales or signs of congestion or edema on chest x-ray). Medical therapy included an intravenous furosemide bolus of 40 mg and a continuous furosemide drip of 125 mg/day followed by an oral furosemide dose of 40 to 80 mg/day. Duration of furosemide treatment was determined by the attending physician based on patient assessment. After randomization, physicians treating group 2 patients were blinded for LI values. In group 3, pre-emptive treatment was begun immediately after randomization. The treatment protocol used in group 3 was identical to that in group 2 except that furosemide treatment was continued until the return of LI to the initial value. Physicians treating these patients were unblinded to LI values. If treatment was not satisfactory, then the diuretic dosage could be changed at the discretion of attending physician. Recommendations for treatment at discharge were provided according to guidelines. After discharge, patients were followed and treated by family physicians. For assessment of long-term outcome, hospital records and computerized clinic databases were reviewed and 6-month telephone contacts with patients were done.

Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). The LI values corresponding to the transition zone from the interstitial to the alveolar stages of pulmonary congestion were assessed by receiver operating curve analysis. Categorical data were presented as count or proportion (percentage). Comparisons among multiple parameters within the same group or different groups were carried out using 1-way analysis of variance. Pearson coefficient was calculated for correlation analysis. Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test were used to detect differences in the prevalence of categorical variables (death and PED) among the 3 groups. Analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis with post hoc test were applied to compare differences in hospital length of stay and peak creatine kinase levels among groups. Multivariate analysis by logistic regression was employed to study parameters associated with length of stay, rehospitalizations, death, and occurrence of new-onset heart failure. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were drawn to show time to death. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used.

Results

In the preliminary phase of the study, we evaluated 65 patients with STEMI (60 ± 12 years old) who had no clinical (Killip class I) or radiographic signs of PED at admission. During 72 hours of monitoring 33 patients with STEMI did not develop clinical and radiologic signs of PED and another 32 well-matched monitored patients developed PED (Killip classes IIA to IV). LI decreased in the former group during hospitalization by 0% to 14% from the initial value and in the latter group by 12% to 27% at the time rales were detected at the lung bases for the first time. Receiver operating curve analysis to discriminate between these groups yielded areas under the curve equal to 0.98 for an LI decrease of 12%, 0.997 for an LI decrease of 13%, 0.996 for 14%, and 0.971 for 15%. Therefore, we selected the LI decrease range 12% to 14% as representing the onset of the transition zone from interstitial to alveolar edema. Attaining this threshold portends evolution to PED with a sensitivity of 96% to 100% and a specificity of 99% to 100%.

For the present study we screened 689 consecutive patients with STEMI without dyspnea. Of these, 77 patients demonstrated signs of heart failure (Killip classes IIA to IIB) on physical examination, and an additional 52 asymptomatic patients (Killip class I) showed radiologic signs of PED on admission. These 129 patients were excluded, and the remaining 560 patients were enrolled and monitored for 84 ± 36 hours. Clinical and laboratory parameters of study groups are presented in Table 1 .

| Variables | Groups | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Group 1 vs 2 | Group 1 vs 3 | Group 2 vs 3 | |

| (n = 347) | (n = 142) | (n = 71) | ||||

| Age (years) | 58.1 ± 11.6 | 61.3 ± 14.1 | 60.0 ± 12.5 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| Men | 84% | 79% | 83% | NS | NS | NS |

| Follow-up (months) | 85.1 ± 26 | 84.9 ± 25 | 84.5 ± 22 | NS | NS | NS |

| Lung impedance at onset (ohm) | 57.0 ± 15.1 | 57.5 ± 15.4 | 57.7 ± 15.3 | NS | NS | NS |

| Echocardiogram during admission | 99.4% | 99.3% | 100% | NS | NS | NS |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 55.1 ± 12.4 | 45.9 ± 12.4 | 46.9 ± 11.8 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33% | 34% | 30% | NS | NS | NS |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 45% | 66% | 66% | 0.0002 | 0.0025 | NS |

| Smoking | 56% | 49% | 58% | NS | NS | NS |

| Hypertension | 53% | 48% | 49% | NS | NS | NS |

| Thrombolytic therapy | 180 (52%) | 70 (49%) | 36 (51%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Primary percutaneous coronary intervention | 139 (40%) | 64 (45%) | 32 (45%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Transient ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 28 (8%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (4%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention during hospitalization (primary percutaneous coronary intervention included) | 319 (91.9%) | 128 (90.1%) | 63 (88.7%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 26 (7.4%) | 13 (9.2%) | 8 (11.3%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 35% | 53% | 49% | 0.0014 | 0.049 | NS |

| Peak creatine kinase (mg/dl) | 1,090 ± 1,136 | 2,078 ± 1,330 | 1,920 ± 1,612 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS |

| Admission/discharge creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.04 ± 0.38/1.07 ± 0.39 | 1.06 ± 0.28/1.10 ± 0.38 | 1.02 ± 0.35/1.07 ± 0.44 | NS | NS | NS |

| Admission hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.3 | 14.1 | 14.3 | NS | NS | NS |

Of the 560 study patients, 347 patients (62%) demonstrated an LI decrease ≤12%. These patients did not report dyspnea and remained at Killip class I during the entire monitoring period (group 1). LI changed during monitoring but maximal LI decrease was only 5.8% (95% confidence interval −0.4 to −12.0, p <0.001 vs initial value). The RS at this time (1.9 ± 1.2) was compatible with interstitial edema and correlated with LI (r = −0.68, p <0.001). Changes of respiratory rate, heart rate, or oxygen saturation from baseline during the follow-up period were not significant.

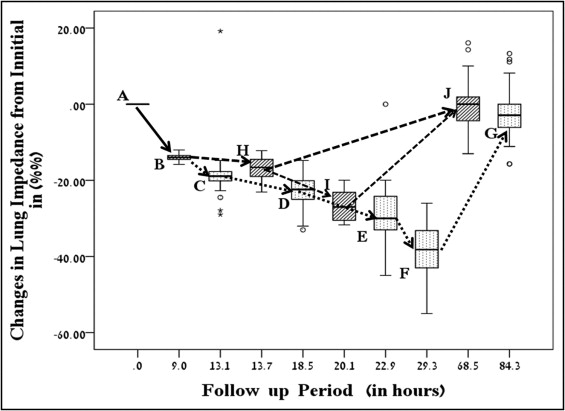

Time that elapsed from the beginning of monitoring to the point LI reached the threshold decrease of 12% to 14% in the 213 patients was 9 ± 7.2 hours (median 7.3, interquartile range 4 to 13). Corresponding RS increased from 0.3 ± 0.4 to 2.8 ± 1.2 (interstitial edema, p <0.01). At this stage, although patients did not yet complain of dyspnea (Killip class I), they were randomized to conventional treatment (n = 142, group 2) and to LI-guided pre-emptive treatment (n = 71, group 3). LI changes and their time of occurrence throughout the monitoring period in groups 2 and 3 are presented in Figure 1 . Time for any event or measurement (i.e., reaching LI threshold level, first detection of rales, etc.) was calculated by averaging that particular period for all patients.

Four hours after randomization (interquartile range 1 to 7), basilar lung rales were first detected (Killip class IIA) in the still asymptomatic group 2, with LI decreasing by 18% (95% confidence interval 14 to 23) and RS increasing to 4.5 (p <0.001 vs baseline). No significant change in clinical parameters was observed at this point (increase in respiratory rate and heart rate and decrease in oxygen saturation, p = NS). Shortly after, at a median of 5.4 hours (interquartile range 1 to 8), patients began to report shortness of breath, with LI decreasing by 26 ± 4% and RS increasing to 5.6 ± 0.9 (p <0.001). Respiratory rate and heart rate increased (p <0.01) and oxygen saturation decreased (p <0.01) and treatment was initiated. Despite treatment, PED progressed with further LI decrease and increasing corresponding RSs (p <0.001; Figure 1 ). In 132 patients (93%) progression of PED was halted at Killip classes IIC to III, whereas in 10 patients (7%) it progressed to cardiogenic shock (Killip class IV), with 6 patients (4%) dying owing to pump failure. At hospital discharge, LI and RS significantly improved in surviving patients (p <0.01; Figure 1 ).

LI-guided pre-emptive treatment was begun in group 3 in the asymptomatic stage (Killip class I) immediately after randomization at an LI decrease of 13.8 ± 0.6% from baseline (p <0.001; Figure 1 ). LI decrease was halted after treatment at an LI decrease of 17 ± 2.6% (p <0.01) in 63 patients (89%). These patients remained asymptomatic. Only 8 patients in group 3 (11%) developed clinically overt PED (Killip classes IIC to III) with an LI decrease of 25 ± 4% (p <0.01; Figure 1 ). While on treatment, they achieved an LI return to baseline value. The proportion of patients in group 3 who developed PED (11%) was smaller than that in group 2 (100%, p <0.0001). No patient in group 3 progressed to cardiogenic shock. Compared to group 2, no death occurred in group 1 or 3 during hospitalization (p <0.01). LI correlated with RS (r = −0.9, p <0.01) in groups 2 and 3. A lower furosemide dosage was used in group 3 than in group 2 (p <0.001; Table 2 ). Discharge medications were based on current guidelines as presented in Table 2 .

| Variables | Groups | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Group 1 vs 3 | Group 1 vs 3 | Group 2 vs 3 | |

| (n = 347) | (n = 142) | (n = 71) | ||||

| Total furosemide (mg) | 0 | 363 ± 363 | 176 ± 162 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac care unit length of stay (days) | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 3.0 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.028 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 7.9 ± 5.4 | 5.5 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | <0.0001 |

| Discharge medications | ||||||

| Aspirin | 97% | 96% | 96% | NS | NS | NS |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker | 96% | 97% | 95% | NS | NS | NS |

| β Blockers | 97% | 96% | 93% | NS | NS | NS |

| Statins | 97% | 94% | 97% | NS | NS | NS |

| Clopidogrel | 93% | 89% | 88% | NS | NS | NS |

| Furosemide | 0% | 42% | 9% | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Spironolactone | 0% | 51% | 10% | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Digitalis | 2% | 16% | 3% | <0.0001 | 0.672 | 0.006 |

| Nitrates | 9% | 19% | 9% | NS | NS | NS |

| 1-year rehospitalization rate for cardiovascular disease/100 patients | 15% | 100% | 56% | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Long-term left ventricular ejection fraction increase (%) | 1.2 ± 4.8 | 2.8 ± 8.3 | 6.8 ± 6.7 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 6-year incidence of new-onset heart failure | 3.3% | 37.3% | 18.3% | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6-year mortality | 6.1% | 19.7% | 7.0% | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.016 |

Lengths of stay in the coronary care unit and in the hospital are presented in Table 2 . After adjustment for variables, we found that group 2 required a longer length of stay in the hospital compared to groups 1 and 3 (p <0.0001; Table 3 ).

| Variables | LOS >5 Days | 1-Year Rehospitalization | 6-Year New HF | 6-Year Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age ⁎ | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.013 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.063 | 1.03 (1.001–1.06) | 0.013 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.008 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) † | ||||||||

| ≤30 | ND | 0.66 | ND | 0.81 | 19.70 (6.43–60.2) | <0.0001 | 7.48 (2.52–22.1) | <0.0001 |

| 31–40 | 3.36 (1.41–8.05) | 0.006 | 1.93 (0.71–5.25) | 0.19 | ||||

| 42–50 | 1.17 (0.47–2.92) | 0.74 | 2.21 (0.91–5.38) | 0.08 | ||||

| Maximal creatine kinase ‡ | ||||||||

| Quartile 2 388–1,100 | 0.99 (0.52–1.89) | 0.98 | ND | 0.64 | ND | 0.86 | ND | 0.11 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.59 (0.80–3.16) | 0.19 | ||||||

| Quartile >2,216 | 2.82 (1.42–5.60) | 0.003 | ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction localization (anterior vs other) | 1.53 (0.94–2.49) | 0.08 | 1.1 (0.69–1.72) | 0.7 | 1.10 (0.54–2.21) | 0.80 | 0.92 (0.45–1.90) | 0.83 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 (0.71–2.16) | 0.44 | 1.84 (1.09–3.09) | 0.022 | 2.34 (1.13–4.85) | 0.022 | 2.56 (1.16–5.67) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 0.76 (0.47–1.23) | 0.27 | 1.19 (0.77–1.86) | 0.44 | 2.31 (0.66–2.59) | 0.44 | 1.16 (0.56–2.38) | 0.7 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.75 (0.45–1.27) | 0.29 | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) | 0.065 | 0.60 (0.29–1.24) | 0.17 | 0.51 (0.23–1.11) | 0.09 |

| Current smoking | 0.71 (0.44–1.15) | 0.17 | 1.2 (0.76–1.88) | 0.44 | 0.97 (0.48–1.95) | 0.93 | 1.11 (0.53–2.32) | 0.78 |

| Admission creatine (change +0.1 mg/dl) | 1.06 (0.54–2.09) | 0.06 | 0.93 (0.49–1.81) | 0.84 | 0.66 (0.26–1.74) | 0.42 | 1.39 (0.59–3.25) | 0.45 |

| Admission hemoglobin (change +0.1 g/dl) | 0.90 (0.78–1.05) | 0.19 | 0.98 (0.85–1.12) | 0.72 | 1.13 (0.92–1.38) | 0.24 | 0.96 (0.78–1.19) | 0.73 |

| Adjustment for these variables compared to group 1 | ||||||||

| Group 2 | 5.28 (3.10–8.99) | <0.0001 | 3.62 (2.16–6.06) | <0.0001 | 15.7 (6.15–40.1) | <0.0001 | 3.46 (1.56–7.69) | 0.002 |

| Group 3 | 1.40 (0.73–2.68) | 0.31 | 1.78 (0.96–3.29) | 0.066 | 4.52 (1.55–13.17) | 0.006 | 1.0 (0.32–3.16) | 1.0 |

| Adjustment for these parameters compared to group 3 | ||||||||

| Group 2 | 3.41 (1.56–7.48) | 0.002 | 3.2 (1.13–9.01) | 0.028 | ||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree