The investigators describe the clinical course of a 26-year-old-man who was brought to the emergency department in a comatose state with status epilepticus after smoking a large amount of crack cocaine. In the emergency department, he was intubated because of depressed mental status and respiratory acidosis. His troponin I remained negative, and electrocardiography showed wide-complex tachycardia with a prolonged corrected QT interval. Because of the corrected QT interval prolongation and wide-complex tachycardia, the patient was started on intravenous magnesium sulfate and sodium bicarbonate. Despite these interventions, no improvement in cardiac rhythm was observed, and electrocardiography continued to show wide-complex tachycardia. The patient became more unstable from a cardiovascular standpoint, with a decrease in blood pressure to 85/60 mm Hg. He was then given 100 ml of 20% lipid emulsion (Intralipid). Within 10 minutes of starting the infusion of 20% lipid emulsion, wide-complex tachycardia disappeared, with an improvement in systemic blood pressure to 120/70 mm Hg. Repeat electrocardiography after the infusion of intravenous lipid emulsion showed regular sinus rhythm with normal QRS and corrected QT intervals. The patient was successfully extubated on day 8 of hospitalization and discharged home on day 10. His cardiac rhythm and blood pressure remained stable throughout his further stay in the hospital.

Emergency management of acute cocaine intoxication relies mainly on supportive and symptomatic treatment, with liberal use of γ-aminobutyric acid receptor agonists such as benzodiazepines. Intravenous lipids have been used successfully to treat cardiac toxicity associated with a variety of lipid-soluble drugs, such as local anesthetics, calcium channel blockers, β blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and cocaine. We describe a young man with cocaine-induced wide-complex tachycardia, cardiovascular instability, and status epilepticus who showed rapid improvement after treatment with intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE).

Case Description

A 26-year-old-man was brought to the emergency department (ED) unresponsive with recurrent seizures. According to the history given by his girlfriend, the patient had smoked a large amount of crack cocaine throughout the night. That morning, he had 2 generalized tonic-clonic seizures, followed by loss of consciousness. His medical history was negative for any major medical problems or hospital admissions. He had a history of cigarette smoking since 9 years of age and multiple substance abuse for the past 1 to 2 years. After arrival to the ED, the patient developed status epilepticus requiring repeated doses of intravenous lorazepam followed by a loading dose of phenytoin (15 mg/kg). His seizures were eventually controlled with a continuous midazolam infusion. Vital signs were as follows: temperature 36.8°C, heart rate 136 beats/min, respiratory rate 26 breaths/min, blood pressure 125/80 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 96% on oxygen through a nonrebreather face mask. The patient was nonverbal, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 5. In addition to tachycardia, his heart rhythm was irregular, with normal S1 and S2. Peripheral perfusion and pulses were good and equal in all extremities. Neurologic examination revealed hyperreflexia, ankle clonus, and intermittent rhythmic movements of the mouth, which were interpreted as seizure activity.

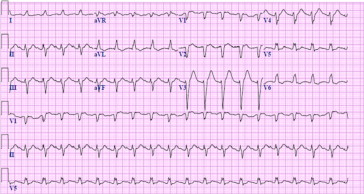

The patient was intubated in the ED because of depressed mental status and respiratory acidosis on arterial blood gas analysis (pH 7.26, pCO 2 59 mm Hg, bicarbonate 23.5 mmol/L, and base deficit 1.8). His hemoglobin was 15.7 g/dl, his white blood count was 18,800 cells/mm 3 with 60% neutrophils and 24% lymphocytes, and his platelet count was 344,000/mm 3 . Troponin I level was <0.017 ng/ml, and creatine phosphokinase level was 2,670 U/L. Troponin remained negative, and creatine phosphokinase peaked at 39,151 U/L 18 hours after admission. The patient’s urine and serum drug screens were positive for cocaine. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry revealed the presence of cocaine and levamisole in his urine. Initial chest radiography before intubation showed mild pulmonary congestion, and the results of computed tomography of the head were normal. Initial electrocardiography revealed wide-complex tachycardia (QRS interval 148 ms) with a prolonged corrected QT interval of 595 ms ( Figure 1 ).

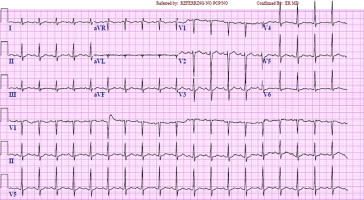

After intubation, the patient’s respiratory acidosis improved (pH 7.36, pCO 2 49). He was started on magnesium sulfate (2 g over 15 minutes) and sodium bicarbonate (50 mEq over 10 minutes) intravenous infusions because of corrected QT interval prolongation and wide-complex tachycardia. Despite these interventions, no improvement in cardiac rhythm was observed, and electrocardiography continued to show wide-complex tachycardia ( Figure 2 ). At this point, the patient became more unstable from a cardiovascular standpoint, with a decrease in blood pressure to 85/60 mm Hg. Because cocaine is a local anesthetic and a lipophilic drug, he was given a 100-ml 20% ILE (Intralipid; Frasenius Kabi, Uppsala, Sweden). Within 10 minutes of starting the ILE infusion, wide-complex tachycardia narrowed, with an improvement in systemic blood pressure. Repeat electrocardiography after ILE infusion ( Figure 3 ) showed a regular sinus rhythm with normal QRS (82 ms) and corrected QT (412 ms) intervals. After initial management in the ED, the patient was transferred to the neurologic intensive care unit for further management. His hospital course was complicated by aspiration pneumonia requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics. He was successfully extubated on day 8 of hospitalization and discharged home on day 10. His cardiac rhythm and blood pressure remained stable throughout his stay in the intensive care unit. Transthoracic echocardiography performed on day 2 of hospitalization revealed normal ventricular size and function, with an estimated ejection fraction of 55% to 60%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree