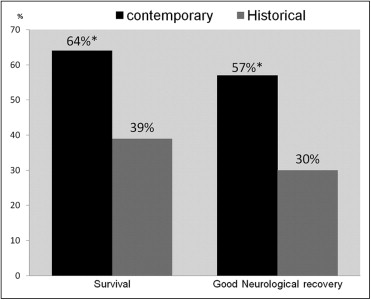

Survival rates after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) continue to be poor. Recent evidence suggests that a more aggressive approach to postresuscitation care, in particular combining therapeutic hypothermia with early coronary intervention, can improve prognosis. We performed a single-center review of 125 patients who were resuscitated from OHCA in 2 distinct treatment periods, from 2002 to 2003 (control group) and from 2007 to 2009 (contemporary group). Patients in the contemporary group had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors but similar cardiac arrest duration and prehospital treatment (adrenaline administration and direct cardioversion). Rates of cardiogenic shock (48% vs 41%, p = 0.2) and decreased conscious state on arrival (77% vs 86%, p = 0.2) were similar in the 2 cohorts, as was the incidence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (33% vs 43%, p = 0.1). The contemporary cohort was more likely to receive therapeutic hypothermia (75% vs 0%, p <0.01), coronary angiography (77% vs 45%, p <0.01), and percutaneous coronary intervention (38% vs 23%, p = 0.03). This contemporary therapeutic strategy was associated with better survival to discharge (64% vs 39%, p <0.01) and improved neurologic recovery (57% vs 29%, p <0.01) and was the only independent predictor of survival (odds ratio 5.5, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 26.2, p = 0.03). Longer resuscitation time, presence of cardiogenic shock, and decreased conscious state were independent predictors of poor outcomes. In conclusion, modern management of OHCA, including therapeutic hypothermia and early coronary angiography is associated with significant improvement in survival to hospital discharge and neurologic recovery.

In a previous study conducted in Australia before the widespread adoption of postresuscitation strategies such as cooling, survival after admission to hospital for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) was 25%, comparable to most registry data. Given the rapid uptake of such approaches since that time, we hypothesized that advances in basic life support and postresuscitation hospital care have improved outcomes. Accordingly, we performed a single-center retrospective review of all patients with OHCA admitted to our hospital from 2002 to 2003 and from 2007 to 2009.

Methods

Melbourne has approximately 3.9 million inhabitants, which is served by a comprehensive centrally co-ordinated ambulance system, which is described elsewhere. The Alfred Hospital (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) is a large tertiary-/quaternary-care referral center that provides 24-hour emergency coronary and cardiac surgical interventions for patients with acute coronary syndromes.

In this retrospective analysis we evaluated clinical characteristics and outcomes of all patients who had an out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation arrest with sustained return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), defined as >20 minutes, and who were subsequently hospitalized at the Alfred Hospital. Analysis was performed for 2 treatment periods: a modern treatment paradigm, 2007 to 2009 (contemporary group), and a historical control group, 2002 to 2003. Data were obtained from Ambulance Victoria and hospital records. The study was performed in accordance with the Alfred Hospital ethics committee guidelines. Interrogation of the hospital database identified 326 patients with presumed OHCA. Seventy-seven patients were excluded secondary to noncardiac causes such as trauma, stroke, and drug overdose. Excluded were 4 patients who did not have ROSC on arrival, 11 patients transferred from other institutions, and 109 patients because of asystole or pulseless electrical activity as their initial rhythm. Our study population, therefore, consisted of 125 patients with OHCA secondary to ventricular arrhythmia.

Ambulance Victoria uses a 2-tier system of ambulance paramedics, most of whom have advanced life support skills, and intensive care paramedics who are authorized to perform endotracheal intubation and administer a range of cardiac drugs. Melbourne also uses a medical emergency response program in which ambulance and fire brigade services respond to cardiac arrests. Cardiac arrest protocols follow the recommendations of the Australian Resuscitation Council. After hemodynamic stabilization, patients are transported urgently to the nearest hospital.

In the 2 treatment periods, hospital care for patients with OHCA was modeled on relevant International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation guidelines at the time. Decision regarding need for cardiac catheterization was made by the treating cardiologist. Intensive care treatment including target hemodynamic and metabolic parameters and choice of inotropic agents were decided by the treating physician according to general critical care guidelines. Therapeutic hypothermia was induced and maintained through a combination of ice-cold intravenous fluids, simple ice packs, and surface cooling blankets. The 2 significant changes to postresuscitative care in patients with OHCA during the study period were use of mild therapeutic hypothermia for unconscious patients (to preserve neurologic function) and increasing use of emergency coronary angiography to assess and treat underlying coronary artery disease as the cause for OHCA.

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcome was “good” neurologic recovery, defined as cerebral performance categories (CPCs) 1 and 2. The CPC is a simple-to-use widely used cerebral performance measurement.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 16 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Numerical normally distributed data were analyzed using Student’s t test (presented as mean ± SD) and non-normal data were compared by Mann-Whitney test (presented as median with interquartile range). Proportions were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test. A p value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Prognostic factors that were found to be significant (p <0.10) in preliminary univariate analyses were entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis. All variables were entered into the equation simultaneously to control for effects of confounding (a subsequent stepwise analysis provided similar results).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1 . Important prehospital factors including rates of witnessed cardiac arrest, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, time until ROSC, and adrenaline administration by paramedics were similar in the control and contemporary cohorts. On arrival to the emergency department the incidence of cardiogenic shock, defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or requiring inotropic support, did not differ significantly between treatment periods (41% vs 48%, p = NS) and rates of decreased conscious state requiring intubation did not differ significantly (86% vs 77%, p = NS).

| Characteristic | Control | Contemporary | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 44) | (n = 81) | ||

| Age (years) | 64 ± 17 | 61 ± 16 | NS |

| Men | 34 (77%) | 68 (84%) | NS |

| Current/ex-smoker | 10 (23%) | 45 (56%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (7%) | 9 (11%) | NS |

| Hypertension | 13 (30%) | 47 (58%) | <0.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (11%) | 37 (46%) | <0.01 |

| History of coronary disease | 14 (32%) | 28 (35%) | NS |

| Initial rhythm | |||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 40 (91%) | 77 (95%) | NS |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 4 (9%) | 4 (5%) | NS |

| Basic life support | |||

| Witnessed arrest | 41 (93%) | 75 (93%) | NS |

| Bystander resuscitation | 33 (75%) | 57 (70%) | NS |

| Ambulance response | |||

| Call to arrival (minutes) | 6 (5–9) | 7 (6–10) | NS |

| Total time until return of circulation (minutes) | 26 (15–35) | 23 (14–30) | NS |

| Number of shocks | 3.9 ± 3.5 | 3.8 ± 4.3 | NS |

| Adrenaline administration | 35 (80%) | 58 (72%) | NS |

| Cause | |||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 30 (68%) | 50 (62%) | NS |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarct | 19 (43%) | 27 (33%) | NS |

| Condition on arrival to hospital | |||

| Unconscious | 38 (86%) | 62 (77%) | NS |

| Cardiogenic shock | 18 (41%) | 39 (48%) | NS |

| Interventions | |||

| Therapeutic hypothermia | 0 (0%) | 61 (75%) | <0.01 |

| Coronary angiography | 20 (45%) | 62 (77%) | <0.01 |

| Emergent angiography | 11 (25%) | 49 (61%) | <0.01 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 10 (23%) | 31 (38%) | 0.03 |

| Coronary bypass graft surgery | 0 (0%) | 4 (5%) | NS |

In the contemporary treatment group 75% of all patients received therapeutic hypothermia, representing 98% of comatose patients after ventricular fibrillation ( Table 1 ). No patients in the control group received therapeutic hypothermia. Rates of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were significantly increased in the contemporary treatment group (77% vs 45%, p <0.01; 38% vs 23%, p = 0.03, respectively; Table 1 ). Of patients undergoing coronary angiography, 50% of patients did not go on to PCI for various clinical reasons ( Table 2 ). PCI was successful in >90% of patients in the 2 treatment groups (see Table 3 ). Incidence of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as the culprit infarct-related artery was higher in the control group (53% vs 27%, p = 0.02). Multivessel disease (defined as multiple coronary lesions with >50% stenosis) was more prevalent in the contemporary treatment group (50% vs 11%, p <0.01).

| Coronary Angiographic Variable | Control | Contemporary | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 20) | (n = 62) | ||

| Normal | 6 (32%) | 13 (21%) | 0.36 |

| Single-vessel disease | 12 (63%) | 17 (27%) | 0.02 |

| Multivessel disease | 2 (11%) | 31 (50%) | 0.01 |

| Coronary arteries >50% stenosis, mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | NS |

| Infarct-related artery | |||

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 10 (53%) | 17 (27%) | 0.02 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 0 (0%) | 6 (12%) | NS |

| Right coronary artery | 1 (5%) | 14 (23%) | NS |

| Grafts | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | NS |

| Left main coronary artery | 1 (5%) | 3 (2%) | NS |

| Multivessel with no clear culprit | 2 (10%) | 8 (16%) | NS |

| Preintervention Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction grade 0–2 flow | 8 (42%) | 23 (47%) | NS |

| Thrombus-containing lesion | 4 (21%) | 11 (22%) | NS |

| Variable | Historical Control PCI (n = 10) | Modern PCI (n = 31) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural success | 9 (90%) | 29 (94%) | NS |

| Final Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction grade 3 flow | 8 (80%) | 28 (90%) | NS |

| Door-to-balloon time (minutes) | 145 (112 to 345) | 120 (105 to 167) | NS |

| Stents per patient | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.03 |

| Mean stent length (mm) | 17.9 ± 5 | 19.8 ± 10 | NS |

| Mean stent diameter (mm) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 3 | NS |

| Drug-eluting stents | 0 (0%) | 7 (23%) | NS |

| Multivessel intervention | 0 (0%) | 6 (19%) | NS |

| Peak troponin mean (range) | 92 (0–186) | 53 (0–179) | NS |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 4 (40%) | 8 (30%) | NS |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 4 (40%) | 23 (56%) | NS |

| Aspiration catheter | 0 | 5 (16%) | NS |

Survival to hospital discharge in the contemporary treatment group was 64% compared to 39% in the historical control (p <0.01). Discharge with favorable neurologic outcome (CPC 1 or 2) was also significantly improved (57% vs 30%, p = 0.01; Figure 1 ). Of survivors in the contemporary treatment group, 89% made a good neurologic recovery. Cause of death was similar in the 2 periods with 70% of patients dying due to poor neurologic outcome, 25% due to persistent cardiac dysfunction, and 5% due to multiorgan failure. Unadjusted predictors associated with survival are presented in Table 4 . Survivors were significantly more likely to be managed by the contemporary treatment paradigm and undergo coronary angiography and successful PCI. In unconscious patients, there was a significant increase in survival (61% vs 37%, p = 0.03) and good neurologic outcome (54% vs 27%, p = 0.01) in those patients receiving therapeutic hypothermia. When adjusting for key prehospital and postresuscitative factors ( Figure 2 , Table 5 ), negative predictors of survival included cardiogenic shock, resuscitation times >20 minutes, and decreased conscious state. The contemporary treatment regimen was a significant independent predictor of survival (odds ratio 5.5, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 26.2, p = 0.03).

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.24 | 0.11–0.5 | 0.01 |

| Basic life support | |||

| Bystander resuscitation | 3.3 | 1.5–7.5 | 0.01 |

| Ambulance response | |||

| Return of circulation >20 minutes | 0.08 | 0.03–0.21 | 0.01 |

| Number of shocks | 0.83 | 0.73–0.94 | 0.01 |

| Condition on arrival | |||

| Unconscious | 0.29 | 0.10–0.84 | 0.02 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0.11 | 0.05–0.26 | 0.01 |

| Interventions | |||

| Cooling ⁎ | 2.7 | 1.1–6.4 | 0.02 |

| Coronary angiography | 7.6 | 3.2–17.5 | 0.01 |

| Successful coronary intervention | 2.1 | 0.95–4.4 | 0.07 |

| Contemporary management | 2.9 | 1.3–6.1 | 0.01 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree