Chapter 37 Upper Airway Disease

Rhinitis and Rhinosinusitis

Rhinitis

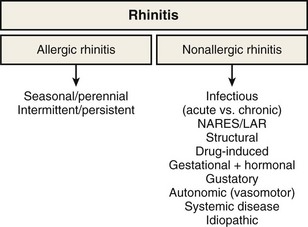

Rhinitis is defined as the presence of two or more symptoms of nasal discharge (anterior or posterior), blockage with sneeze, or itch for more than 1 hour on most days. It is an umbrella term that encompasses multiple diseases with distinct immunopathogenic mechanisms and correspondingly specific diagnostic and treatment strategies (Figure 37-1). Although rhinitis is subdivided into two broad categories of allergen-induced rhinitis and nonallergic rhinitis, disease overlap is common. Thus, a careful history and directed investigations are required to establish the exact diagnosis. In practice, inflammatory changes usually are continuous from nasal to sinus mucosa (see Figure 37-1); therefore, the designation rhinosinusitis is more accurate, although its use may lead to clinical confusion with the separate group of diseases that are historically classified under sinusitis. Apart from viral colds, allergic rhinitis (AR) is the most common cause of nasal symptoms.

Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathophysiology

Allergic Rhinitis

Up to 30% of adults and 40% of children are affected, and worldwide the prevalence of AR continues to increase (Figure 37-2). The condition has marked effects on quality of life and is responsible for reduced school and workplace attendance (by 3% to 4%) and performance (by 30% to 40%). The resulting economic burden is high, and rhinitis and related AR are common. It is estimated that nearly 500 million people worldwide have AR, and it is one of the most common reasons for attendance with a primary care practitioner.

Figure 37-2 Global prevalence of hay fever in 13- to 14-year-olds.

(From Strachan D, Sibbald B, Weiland S, et al: Worldwide variations in prevalence of symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood [ISAAC], Pediatr Allergy Immunol 8:161–176, 1997.)

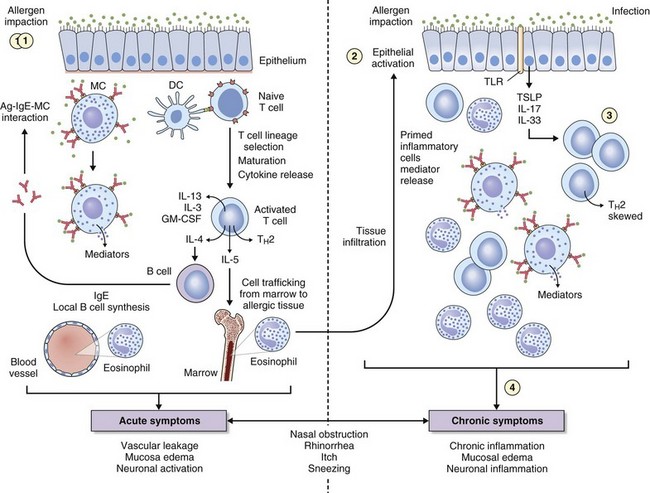

The key immunologic event that initiates AR is binding of allergen to specific IgE on mast cells found in the nasal mucosa. Cross-linking of two or more high-affinity IgE molecules in response to allergen binding leads to mast cell activation and degranulation with release of mediators, initiating an immune cascade (Figure 37-3). This is termed the immediate response. With the release of histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, bradykinin, and other mediators (platelet-activating factor, substance P, tachykinins) comes the immediate onset of symptoms of sneezing, itching, and “running,” typically seen in instances of intermittent allergen contact—for example, with hay fever. An additional immunologic event in up to 70% of affected persons is a further influx of inflammatory cells consisting predominantly of eosinophils, basophils, and T cells expressing TH2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4 (B cell IgE class switching) and IL-13 (mucus hypersecretion). Clinically this process is characterized by further obstruction, decreased olfaction, and mucosal irritability with immunopathologic changes similar to those seen in chronic asthma (see Figure 37-3). Local mucosal allergen–specific IgE production by nasal B cells is now confirmed and leads to local (skin prick test–negative) rhinitis. Emerging evidence also indicates that activated nasal epithelium–derived cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-25 (i.e., IL-17E), and IL-33 can further promote disease through initiation, enhancement, and maintenance of TH2 inflammation at the mucosal surface where allergen deposition and sampling occur. In addition, the potential for innate mucosal immune mechanisms such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling system to drive or skew TH2 responses is increasingly recognized.

Nonallergic Rhinitis

Nonallergic, Noninfectious Rhinitis

By definition, patients with nonallergic rhinitis (NAR) are skin prick–negative for common aeroallergens. NAR occurs in around 25% of persons with rhinitis symptoms. However, mixed rhinitis (a combination of allergic and nonallergic forms) can occur in up to 44% to 87% of patients. NAR incidence is higher in women. The nonallergic form of rhinitis incorporates a very heterogeneous group of conditions, and it is possible to further subclassify NAR into etiologic subtypes: a group for which the etiology is known and one for which it cannot be established, termed idiopathic rhinitis. The latter type is a diagnosis of exclusion, and approximately 60% of NAR cases will fall into this category. A summary of considerations in the differential diagnosis for NAR is presented in Box 37-1. An essential division is between NAR with eosinophilic inflammation in the upper airway and that without.

Nonallergic Rhinitis Without Eosinophilia

Autonomic Rhinitis

The nasal mucosa receives a rich efferent innervation from both the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. Nasal glandular secretion is largely mediated by the parasympathetic fibers, the main postganglionic neurotransmitter being acetylcholine (ACh) acting through muscarinic receptors (predominantly the M3 subtype). The sympathetic fibers mediate vascular tone and can regulate nasal airflow by potent effects on venous erectile tissue. The primary neurotransmitter is norepinephrine (noradrenaline). In autonomic rhinitis, there is no evidence of nasal inflammation, but of autonomic dysfunction or imbalance. Nasal and, in some patients, cardiovascular reflexes are abnormal, and there may be association with the chronic fatigue syndrome. Topical ipratropium is useful in decreasing watery rhinorrhea; capsaicin applications also may relieve symptoms for several months after a few weeks of treatment. Epinephrine (adrenaline) and other sympathomimetics lead to vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa, with increased nasal patency. Both α- and β-adrenergic blockers increase nasal resistance and can produce symptoms of nasal stuffiness (Box 37-2). Stimulation of the parasympathetic system leads to an increase in nasal secretions. However, patients who have this condition also have increased responsiveness to both histamine and methacholine, which results in nasal blockage and rhinorrhea. It also is associated with hypertrophy of the inferior turbinates, and nasal polyps are sometimes present. Certain stimuli such as cold air, exercise, mechanical or thermal factors, and humidity changes result in rhinorrhea and other symptoms of rhinitis, and a period of nasal hyperresponsiveness often follows viral infection. This observation is consistent with general neuronal dysregulation leading to excessive and troublesome neural hyperreactivity and imbalance with certain environmental exposures.

Drug-Induced Rhinitis

The main drugs implicated in pharmacologic rhinitis are listed in Box 37-2. This entity is mostly noninflammatory—for example, antihypertensives, particularly beta blockers, can cause nasal obstruction by abrogation of the normal sympathetic tone, which maintains nasal patency. Exogenous estrogens in oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy also evoke rhinitis in some patients. Overuse of α-agonists results in rhinitis medicamentosa: a tachyphylaxis of α-receptors to extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli. The mucosa becomes swollen and reddened. Aspirin hypersensitivity is an inflammatory form of drug-induced rhinitis (see earlier).