The publication of consensus group guidelines provides an opportunity to standardize practices through evidence-based protocols. Variations in patient care have been shown to result in disparities in patient outcomes, whereas protocols streamline the clinical decision-making process and reduce variation. By enhancing the speed and accuracy of evaluation and treatment, efficiency can be optimized and outcomes improved.

Clinical protocols were first applied to the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in the 1990s through algorithms used to manage patients with acute chest pain. Effective protocols have since emerged as a means to improve patient outcomes by standardizing and coordinating care from presentation to postdischarge and subsequent follow-up. Although protocols can serve as a useful guide for providers, modifying care according to individual patient characteristics and specific clinical situations is essential to ensure appropriate provision of care. The goals of an effective protocol are to define standards of practice (informed by clinical practice guidelines), reduce unnecessary variability, coordinate different aspects of care, enhance efficiency, and improve the quality of care. In this report, we review important considerations and challenges in creating institution-specific protocols for patients with ACS informed by consensus guidelines. We further present a concrete example from our institutional experience of implementing an ACS protocol and conclude by describing the critical role of registry-based reporting for continuous feedback and quality improvement after protocol implementation.

Updates to Guidelines

In 2013, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) published guidelines for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) that replaced the 2004 guidelines and subsequent updates published in 2007 and 2009. Similar guidelines for the management of STEMI were published by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in 2012, replacing previous guidelines from 2003 and corresponding update in 2008. Guidelines for non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) were published by the ACCF/AHA and ESC in 2012 and 2011, respectively, replacing previous versions from 2007.

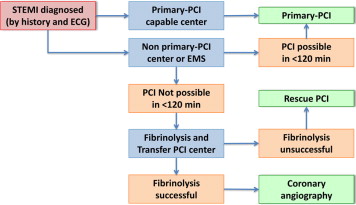

In the most recent guidelines for the management of STEMI, particular emphasis is placed on the development and organization of systems of care, including algorithms for patient transfer to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)–capable facilities. Additional focus in both STEMI and NSTEMI guidelines is placed on novel antithrombotic and anticoagulant therapies, advances in PCI, and strategies for patient-centered secondary prevention.

A comparison of the US and the European guidelines highlights several important differences between recommendations, particularly with regard to antiplatelet therapy. Although both guidelines recommend the early use of aspirin for STEMI, the ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend using 162 to 325 mg initially and 81 to 325 mg continued each day indefinitely (IA), with 81 mg preferred (IIaB), whereas the ESC guidelines recommend 150 to 300 mg initially followed by 75 to 100 mg/day. With regard to second antiplatelet agents in STEMI, ACCF/AHA guidelines support clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor with equal recommendation class (IB), whereas the ESC guidelines state a preference for prasugrel or ticagrelor over clopidogrel (IB).

In comparing the US and the European guidelines for NSTEMI, recommended dosages of aspirin again differ, with ACCF/AHA recommending 162 to 325 mg initially (or 75 to 162 mg/day for elevated bleeding risk) and 81 mg/day afterward versus ESC recommending 150 to 300 mg initially followed by 75 to 100 mg/day, both continuing indefinitely (IA). With regard to addition of a second antiplatelet agent during NSTEMI, ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend clopidogrel or ticagrelor loading before PCI followed by daily maintenance dose (IB; vs prasugrel or ticagrelor dosing at the time of PCI), whereas ESC guidelines recommend prasugrel and ticagrelor administration (IB), yielding that clopidogrel should only be used when these former agents are unavailable (IC). Similarly, for patients who underwent primarily conservative treatment strategies for NSTEMI, ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend clopidogrel or ticagrelor (IB), whereas ESC guidelines prefer ticagrelor (IB) over clopidogrel (IC).

Creating Protocols

The development of a clinical protocol capable for use at an individual institution involves processes that differ depending on both diagnosis type and institutional capabilities. Designing a protocol for ACS requires a multidisciplinary approach with input from cardiologists, emergency medicine physicians, nursing staff, administrators, laboratory personnel, pharmacies, and patients. Initial planning steps entail evaluation of both current internal practices and external institutional practices, in conjunction with an objective and thorough appraisal of available evidence. Although approaches to evaluating current practices can differ widely, key principles include identifying variations in care, understanding interdependencies (i.e., among various departments and staff) of clinical decisions, and targeting specific goals and outcomes to be measured. The application of available evidence involves institution-specific individualization that depends not only on available resources but also the experience of practitioners with various procedures and treatments.

Published clinical practice guidelines can help serve as a guide for the clinical care outlined within an institution-specific protocol. The introduction of consensus guidelines from groups such as the ACCF/AHA and ESC has aided in the development of clinical protocols by culling together present data to create evidence-based recommendations such as those for the triage and initial management of patients with STEMI ( Figure 1 ). The implementation of such guidelines into clinical practice, however, requires careful evaluation of each recommendation. As updates to these guidelines become available, assessment of benefits of new treatment options must be weighed against costs and risks of introducing a change to an existing system and the limited amount of data that typically comes with a newly approved pharmaceutical compared with established therapeutics. Close prospective monitoring for institution-specific outcomes can also allow evolution and individualized tailoring of protocols.

To keep a clinical protocol updated, regular reviews must take place to incorporate new external data (including trials, postmarketing studies, new Food and Drug Administration approvals) and new internal data (institutional experience). In this way, a continuous quality improvement framework is maintained for the evaluation and potential revision of a protocol. Variance from a given protocol must also be tracked and analyzed to determine causes of variance, effects on outcomes, and methods for improvement. As a general rule, protocols should be updated annually, whenever new consensus guidelines are released and new and relevant trials are published. Such an iterative improvement process has demonstrated significant improvements in ACS outcomes over the past decade as evidence-based protocols for ACS have become prominent.

Creating Protocols

The development of a clinical protocol capable for use at an individual institution involves processes that differ depending on both diagnosis type and institutional capabilities. Designing a protocol for ACS requires a multidisciplinary approach with input from cardiologists, emergency medicine physicians, nursing staff, administrators, laboratory personnel, pharmacies, and patients. Initial planning steps entail evaluation of both current internal practices and external institutional practices, in conjunction with an objective and thorough appraisal of available evidence. Although approaches to evaluating current practices can differ widely, key principles include identifying variations in care, understanding interdependencies (i.e., among various departments and staff) of clinical decisions, and targeting specific goals and outcomes to be measured. The application of available evidence involves institution-specific individualization that depends not only on available resources but also the experience of practitioners with various procedures and treatments.

Published clinical practice guidelines can help serve as a guide for the clinical care outlined within an institution-specific protocol. The introduction of consensus guidelines from groups such as the ACCF/AHA and ESC has aided in the development of clinical protocols by culling together present data to create evidence-based recommendations such as those for the triage and initial management of patients with STEMI ( Figure 1 ). The implementation of such guidelines into clinical practice, however, requires careful evaluation of each recommendation. As updates to these guidelines become available, assessment of benefits of new treatment options must be weighed against costs and risks of introducing a change to an existing system and the limited amount of data that typically comes with a newly approved pharmaceutical compared with established therapeutics. Close prospective monitoring for institution-specific outcomes can also allow evolution and individualized tailoring of protocols.

To keep a clinical protocol updated, regular reviews must take place to incorporate new external data (including trials, postmarketing studies, new Food and Drug Administration approvals) and new internal data (institutional experience). In this way, a continuous quality improvement framework is maintained for the evaluation and potential revision of a protocol. Variance from a given protocol must also be tracked and analyzed to determine causes of variance, effects on outcomes, and methods for improvement. As a general rule, protocols should be updated annually, whenever new consensus guidelines are released and new and relevant trials are published. Such an iterative improvement process has demonstrated significant improvements in ACS outcomes over the past decade as evidence-based protocols for ACS have become prominent.

Challenges of Applying Guidelines

There are 2 main challenges to applying consensus group guidelines when creating a clinical protocol. The first is how to manage areas where there are multiple class I recommendation options within a given aspect of a guideline when only 1 option can be chosen for the purposes of a clinical practice protocol. In the current culture of updating consensus guidelines, new recommendations are added, but unless they specifically implement a change from a previous recommendation, the old recommendations remain along with the new. An example of this is the choice of adjunctive antiplatelet agent to support reperfusion with primary PCI for patients presenting with ACS. In the 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines for the management of STEMI, 3 antiplatelet options (clopidogrel 600 mg, prasugrel 60 mg, and ticagrelor 180 mg) are presented, each a class I recommendation with level of evidence B. The guidelines do not provide guidance on how to distinguish between these 3 options, and it therefore is left to the committee designing the protocol to choose among these agents with identical recommendation classes and strengths of evidence.

This problem will only become more difficult as newer antithrombotic agents are studied and subsequently approved, as it becomes nearly impossible to effectively and comprehensively compare each antithrombotic therapy, particularly when administered in combination and at different times in relation to the patient’s index hospitalization. Furthermore, the primary study hypotheses of many newer antithrombotics use noninferiority testing that often supports the approval of new therapeutics but without demonstrating superiority over another existing treatment option. As a result, this underscores the importance of tailoring clinical protocols to individual institutions according to specific practices, previous experiences, and levels of comfort with new and existing therapeutic approaches.

The second challenge in using consensus recommendations to create protocols is how to implement these guidelines throughout various hospital departments. ACS treatments have been most prominently studied in intensive care unit and medicine floor settings, yet hospital implementation requires utilization in emergency, hospitalist, and surgical departments as well. Not only are patient populations often different in other departments (both from those studied in clinical trials and from those with which institutions have the most experience treating) but providers and staff in various departments are trained differently, have different methods of practice, and will have variable exposure to newly implemented protocols. Thus, distinct and often individualized efforts must be made to implement protocols broadly throughout a hospital to maximize effective protocol utilization and reduce intrahospital variability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree