The American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) have recently updated their joint guidelines for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS, including unstable angina [UA] and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]). These guidelines replace the 2007 guidelines and the focused updates from 2011 and 2012 and now combine UA and NSTEMI into a new classification, NSTE-ACS, and updating the terminology around noninvasive management to ischemia-guided strategy. The latest guidelines include updated recommendations for the use of the oral antiplatelet agents (P2Y 12 inhibitors) prasugrel and ticagrelor as part of dual-antiplatelet therapy—the cornerstone of treatment for these patients. This report provides a comprehensive overview of the new and modified recommendations for the management of patients with NSTE-ACS and the evidence supporting them. Also, where appropriate, similarities and differences between the current recommendations of the AHA/ACC and those of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) are highlighted. For example, the AHA/ACC recommends the P2Y 12 inhibitor ticagrelor over clopidogrel in all patients with NSTE-ACS and clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor for patients in whom percutaneous coronary intervention is planned, whereas the ESC guidelines specifically recommend individual P2Y 12 inhibitors for particular patient subgroups.

Unstable angina (UA) and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) represent a clinical subset of acute coronary syndromes (ACSs). UA and NSTEMI are usually caused by coronary artery disease, with disruption or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque ultimately leading to decreased coronary blood flow. It is associated with an increased risk of subsequent myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular (CV) death. The relative frequency of UA and NSTEMI is increasing, and associated mortality remains relatively high and similar to that of ST-elevation MI (STEMI). Therefore, improving the management of these patients is a challenge.

The American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) have recently updated their joint guidelines for the management of patients with UA and NSTEMI. Importantly, the 2014 update now combines UA and NSTEMI into a new classification, NSTE-ACS, on the basis of these patient populations not always being distinguishable. In addition, the terms medical and noninvasive management have been modified to ischemia-guided strategy. For the purposes of consistency and alignment with the most recent clinical guidance, the updated terminology is used throughout this review where appropriate. Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin (ASA) and a P2Y 12 antagonist remains the cornerstone of management for patients with NSTE-ACS. The updates to the guidelines have been made on the basis of the focused updates since the publication of the 2007 guidelines, that is, the 2011 and 2012 focused updates which primarily included recommendations for the use of the new oral antiplatelet agents (P2Y 12 inhibitors) prasugrel and ticagrelor, respectively, both of which were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after the publication of the 2007 guidelines. Additional updates were also included to make these guidelines consistent with the 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/AHA/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines ; a summary of these recommendations and the 2011 ACCF/AHA guidelines on coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) were also included in the latest update for completeness.

Each recommendation from the AHA/ACC is categorized according to the class of recommendation (COR), which is an estimate for the size of the treatment effect, and level of evidence (LOE), an estimate of the certainty or precision of the effect ( Table 1 ). The new and modified recommendations from the AHA/ACC for the management of patients with NSTE-ACS and the evidence to support them are reviewed. Differences between these guidelines and the 2011 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), which apply similar criteria for COR and LOE, are also highlighted where appropriate.

| Class | Size of treatment effect |

|---|---|

| Class of recommendation | |

| I | Benefit >>>risk Procedure/treatment should be performed/administered |

| II | Benefit >> risk It is reasonable to perform procedure/administer treatment |

| IIb | Benefit ≥ risk Procedure/treatment may be considered |

| III | No benefit or harm Procedure/test is not helpful or treatment has no proven benefit Procedure/test is associated with excess cost without benefit or is harmful; treatment is harmful to patients |

| Level of evidence | |

| Level | Estimate of certainty (precision) of treatment effect |

| A | Multiple populations evaluated ∗ Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| B | Limited populations evaluated ∗ Data derived from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies |

| C | Very limited populations evaluated ∗ Only consensus opinion of experts, case studies, or standard of care |

∗ Data available from clinical trials or registries about the usefulness/efficacy in different subpopulations, such as sex, age, history of diabetes, history of prior myocardial infarction, history of heart failure, and prior aspirin use.

Antiplatelet Therapy

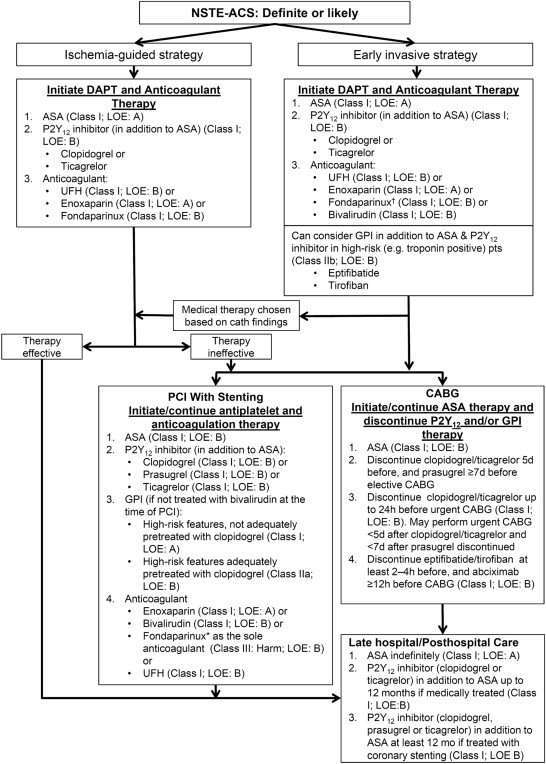

The AHA/ACC recommendations for the use of antiplatelet therapy in patients with a definite or likely diagnosis of NSTE-ACS, additional management strategies for patients receiving antiplatelet therapy, and the long-term use of antiplatelet therapy have been updated with respect to prasugrel and ticagrelor. The recommendations for patients who underwent treatment with an early invasive or an ischemia-guided strategy are summarized in Table 2 . Figure 1 summarizes the COR I and II recommendations for patients with NSTE-ACS.

| Recommendations | Dosing and special considerations | COR | LOE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | |||

| 162–325 mg | I | A |

| 81–162 mg/day | I | A |

| P2Y 12 inhibitors | |||

| 75 mg | I | B |

| I | B | |

| 300 mg or 600 mg loading dose, then 75 mg/day | ||

| 180 mg loading dose, then 90 mg BID | ||

| n/a | I | B |

| n/a | IIa | B |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | |||

|

| IIb | B |

| Parenteral anticoagulant and fibrinolytic therapy | |||

|

| I | A |

|

| I | B |

| 2.5 mg SC daily | I | B |

| n/a | I | B |

|

| I | B |

| n/a | III Harm | A |

∗ The recommended maintenance dose of aspirin to be used with ticagrelor is 81 mg daily.

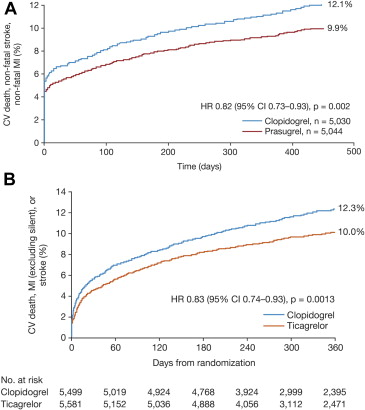

The AHA/ACC recommend the use of prasugrel only in patients for whom PCI is planned and who are not at high risk of bleeding complications, on the basis of the results of the pivotal TRial to assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibitioN with prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) 38. TRITON-TIMI 38 compared the efficacy and safety of prasugrel (60-mg loading dose and 10 mg/day maintenance dose) with clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose and 75 mg/day maintenance dose) in patients with moderate- to high-risk ACS (n = 13,608) who had not received clopidogrel for >5 days before enrollment and in whom PCI was planned. All patients received ASA 75 to 162 mg/day. Of those enrolled, 74% (n = 10,074) had UA/NSTEMI. In the overall cohort, prasugrel was associated with a 19% risk reduction for the primary end point of the composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke compared with clopidogrel at 15 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73 to 0.90, p <0.001), which was largely attributed to a 24% risk reduction for the incidence of nonfatal MI (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.85; p <0.001). The rate of stent thrombosis was also reduced (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.64; p <0.001). Similar results were reported in patients with UA/NSTEMI: an 18% risk reduction for the primary end point in patients receiving prasugrel compared with those receiving clopidogrel (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.93, p = 0.002; Figure 2 ) and a 24% reduction in the risk of nonfatal MI (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.87, p <0.001) were observed. The risk of stent thrombosis was also reduced in patients with UA/NSTEMI (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.72; p <0.001).

Prasugrel was associated with a significantly higher rate of non–CABG-related TIMI-defined major bleeding (2.4% vs 1.8%, p = 0.03), including life-threatening bleeding (p = 0.01) and fatal bleeding (p = 0.002), compared with clopidogrel in the overall cohort in TRITON-TIMI 38. The net clinical benefit (all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and non–CABG-related TIMI major bleeding) in this cohort favored prasugrel (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.95, p = 0.003). The net clinical benefit in patients with UA/NSTEMI also favored prasugrel (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.0, p = 0.043). In a post hoc analysis, prasugrel was not associated with a net benefit in 3 subgroups of patients. There was no evidence of net clinical benefit with prasugrel over clopidogrel in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA; HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.32, p = 0.04), but they had an increased risk of TIMI major bleeding (p = 0.06). Hence, the AHA/ACC guidelines do not recommend the use of prasugrel in patients with a history of stroke or TIA (COR: III [harm], LOE: B). In patients aged ≥75 years and those weighing <60 kg, there was no evidence of net benefit or net harm with prasugrel, with an HR for net clinical benefit of 0.99 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.21, p = 0.92) in those aged ≥75 years and 1.03 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.53, p = 0.89) in those weighing <60 kg. Therefore, the AHA/ACC guidelines do not recommend prasugrel in patients aged ≥75 years because of increased risk of fatal and intracranial bleeding and uncertain benefit, except in high-risk groups (patients with diabetes or a history of MI), in which clinical evidence supports its use. They also do not recommend 10 mg of prasugrel in patients weighing <60 kg because the concentration of the active metabolite of prasugrel versus body weight is greater in these patients and there is an increased risk of bleeding with this daily maintenance dose.

After the publication of the 2007 guidelines and subsequent focused updates, the results of the TRILOGY trial evaluating dual-antiplatelet treatment with prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with high-risk NSTE-ACS selected for an ischemia-guided strategy became available and have been used in the development of the most recent guidelines. Overall, 9,326 patients (aged <75 years: n = 7,243; ≥75 years: n = 2,083) were randomized to prasugrel (10 mg/day; 5 mg/day for those aged ≥75 or <75 years and <60 kg in weight) or clopidogrel (75 mg/day) plus aspirin for ≤30 months. At a median follow-up of 17 months, the primary end point occurred in 13.9% of the prasugrel group and 16.0% of the clopidogrel group (HR in the prasugrel group 0.91; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.05; p = 0.21). A subanalysis confirmed that older age is associated with substantially increased long-term CV risk and bleeding. However, no differences in ischemic or TIMI major bleeding events were observed in elderly patients receiving reduced-dose prasugrel compared with clopidogrel. No significant interactions among weight, pharmacodynamic response, and bleeding risk were observed between reduced-dose prasugrel and clopidogrel in elderly patients. A prespecified secondary analysis in patients aged <75 years found that prasugrel was associated with a lower risk of a primary end point event (CV death, MI, or stroke at 30 months) compared with clopidogrel in the subgroup of patients who had angiography at baseline (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98, p = 0.032) but not in the group who did not undergo angiography (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.20, p = 0.94). Rates of bleeding were similar in the 2 treatment groups, regardless of whether patients underwent angiography.

The recommendations for the use of ticagrelor are based on the results of the pivotal PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) study undertaken in a broad population of patients with ACS (n = 18,624), 11,067 (59.4%) of whom had UA/NSTEMI (7,955 had NSTEMI and 3,112 had UA). Ticagrelor (180-mg loading dose, 90-mg twice daily maintenance dose) reduced the primary composite end point of vascular death, MI, or stroke to 9.8% compared with 11.7% with clopidogrel (300- to 600-mg loading dose, 75 mg/day maintenance dose; HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92, p <0.001) at 12 months. The reduction in the primary end point with ticagrelor was driven by lower rates of both vascular death (4.0% vs 5.1%, HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.91, p = 0.001) and MI (5.8% vs 6.9%, HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.95, p = 0.005). Ticagrelor was also associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (secondary end point: 4.5% vs 5.9%, HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.89; p <0.001 vs clopidogrel), which has not previously been demonstrated with any other P2Y 12 inhibitor. Ticagrelor also reduced the rate of stent thrombosis (p = 0.009 vs clopidogrel).

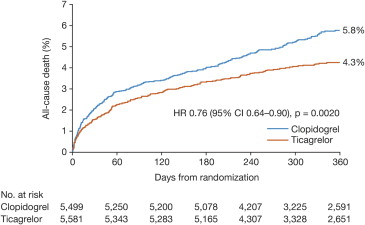

In patients with UA/NSTEMI, ticagrelor reduced the incidence of the primary composite end point compared with clopidogrel (10.0% vs 12.3%, HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.93, p = 0.0013; Figure 2 ), again driven by reductions in vascular death (3.7% vs 4.9%, HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.93, p = 0.007) and MI (6.6% vs 7.7%, HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99, p = 0.042). All-cause mortality was also reduced in patients with UA/NSTEMI (4.3% vs 5.8%, HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.90, p = 0.002; Figure 3 ). The benefits of ticagrelor were evident regardless of the planned or actual management strategy and of clopidogrel pretreatment.

There were no significant differences in the rate of study-defined (PLATO-defined) major bleeding between those receiving ticagrelor and clopidogrel in the entire PLATO cohort (11.6% vs 11.2%, p = 0.43) and those patients with UA/NSTEMI (13.4% vs 12.6%, p = 0.26). There was also no significant difference in the rate of PLATO-defined CABG-related major bleeding in the entire PLATO cohort (p = 0.32) or those patients with UA/NSTEMI (p = 0.56). According to the TIMI definition, there were no significant differences in the rate of major bleeding, CABG-related major bleeding, and major or minor bleeding in the entire PLATO cohort (data have not been presented for TIMI-defined bleeding in the UA/NSTEMI cohort). However, ticagrelor was associated with a higher rate of PLATO-defined non–CABG-related major bleeding in the whole cohort (4.5% vs 3.8%, p = 0.03) and those with UA/NSTEMI (4.8% vs 3.8%, p = 0.014) and with a higher rate of PLATO-defined major or minor bleeding in the entire cohort (16.1% vs 14.6%, p = 0.008) and TIMI-defined non-CABG major bleeding (2.8% vs 2.2%, p = 0.03) but, as previously stated, not TIMI-defined major or minor bleeding (11.4% vs 10.9%, p = 0.33). Fatal intracranial bleeding occurred in 11 patients in the ticagrelor group (0.1%) compared with 1 (0.01%) in the clopidogrel group (p = 0.02). On the basis of the results of the PLATO trial, ticagrelor is recommended in all patients with ACS, irrespective of the initial treatment strategy.

Consistent with the overall trial results, ticagrelor reduced the primary end point and all-cause mortality compared with clopidogrel in patients with a history of stroke or TIA in the PLATO study (n = 1,152; HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.13 and HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.91, respectively). In patients with a history of stroke or TIA, there was no significant difference between the treatments for PLATO-defined major bleeding and CABG-related major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding was infrequent, occurring in 4 patients in each treatment group. Although not specifically covered in the 2014 AHA/ACC guidelines, the 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update stated that the number of patients with previous stroke in PLATO was small, limiting the power to detect differences in intracranial bleeding. On this basis, it seems prudent to consider the potential, and as yet undefined, risk of intracranial bleeding in patients with previous stroke or TIA when considering adding ticagrelor to ASA, as dual-antiplatelet therapy with ASA and either clopidogrel or prasugrel have been shown to increase the risk of intracranial bleeding, particularly in those with previous stroke.

In the PLATO trial, relations between weight and lipid-lowering agents on outcome were observed, but these were not considered to be clinically relevant. The benefits of ticagrelor appear to be attenuated in patients weighing less than the median weight for their gender and in those not taking lipid-lowering agents at the time of randomization. There was also a significant interaction between treatment and geographic region, with attenuated efficacy in North America in the PLATO study (p = 0.045 for interaction). Statistical analyses could not rule out the play of chance in the geographic region interaction, but a substantial fraction of this interaction (80% to 100%) could be explained by the ASA maintenance dose. An ASA-loading dose of 325 mg with a maintenance dose of 75 to 100 mg/day (325 mg/day in patients with stents) was recommended in the PLATO study protocol. However, more patients in the United States took daily ASA doses ≥300 mg after day 2 (61% vs 4% of patients from the rest of the world). Pooling the primary efficacy results for the entire cohort yielded an HR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.86) favoring ticagrelor with ASA maintenance doses ≤100 mg but favored clopidogrel with high ASA maintenance doses (≥300 mg). In patients taking low-dose (≤100 mg) maintenance ASA, ticagrelor was associated with better outcomes than clopidogrel in the United States, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.33); therefore, low maintenance doses of ASA are likely to be associated with the most favorable outcomes. The AHA/ACC recommended a maintenance dose of ASA with ticagrelor of 81 mg/day. They also state that indirect comparisons show similar reductions in the odds of vascular events with ASA doses between 75 mg and 1,500 mg and that bleeding risk increases dose dependently. They recommend an ASA maintenance dose of 81 mg with ticagrelor in patients who have undergone PCI in preference to higher doses (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Although similar reductions in the primary end points of the composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke were achieved with prasugrel and ticagrelor in the TRITON-TIMI 38 and PLATO studies in patients with UA/NSTEMI, respectively, one must consider the differences between these 2 studies. TRITON-TIMI 38 restricted the patient population to those in whom PCI was planned, whereas PLATO enrolled a broader patient population, including medically managed patients and those who underwent CABG; of those patients with UA/NSTEMI, only 47% underwent PCI.

Recommendations regarding the use of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIa) receptor antagonists in patients with NSTE-ACS remain the same as those in the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines, and further data published since 2007 are included to support these recommendations.

Choice of P2Y 12 inhibitor for PCI

The AHA/ACC guidelines recommend clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor in patients for whom PCI with coronary stenting is planned and ticagrelor or clopidogrel for those in whom an early invasive or initial ischemia-guided strategy is planned or the strategy is unknown. The updated guidelines state that it is reasonable to use ticagrelor over clopidogrel in patients who undergo an early invasive or ischemia-guided strategy and prasugrel over clopidogrel in patients who underwent PCI and are not at high risk of bleeding complications. The guidelines recommend against the routine use of prasugrel in patients with NSTE-ACS before angiography ( Figure 1 ). The AHA/ACC state that the reasons underlying the lack of recommendations for specific P2Y 12 inhibitors are that prasugrel and ticagrelor were studied in different populations (both vs clopidogrel), there are no head-to-head studies between these agents, and the loading dose of clopidogrel used in the TRITON-TIMI 38 study was lower than that recommended in the current guidelines. In addition, they state that although some patients may be resistant to clopidogrel, there is little information regarding strategies to select patients who may do better with prasugrel or ticagrelor. The AHA/ACC suggest that an individualized decision about the choice of P2Y 12 inhibitor should consider efficacy and bleeding events as well as clinical experience with a given medication.

In contrast, on the basis of the same data, the ESC guidelines for the management of patients with NSTE-ACS, which are similar to the updated AHA/ACC guidelines in most other respects, specifically recommend individual P2Y 12 inhibitors for particular patient subgroups ( Table 3 ). Ticagrelor is recommended in all moderate- to high-risk patients with NSTE-ACS, irrespective of the planned treatment strategy, including those pretreated with clopidogrel (COR: I, LOE: B). Unfortunately, the ESC guidelines do not define the characteristics of patients at moderate-to-high risk of ischemic events, except to note that patients may have elevated troponin levels, but it would be reasonable to assume that patients with NSTE-ACS similar to those in the PLATO study would be candidates for ticagrelor. This includes patients with NSTE-ACS with ST-segment changes on the electrocardiogram, positive biomarkers of myocardial damage, at least 1 risk factor such as age ≥60 years, a history of significant coronary or cerebrovascular disease (such as previous MI, CABG, or stroke), diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, or chronic renal dysfunction. Prasugrel is recommended in P2Y 12 -inhibitor–naive patients, particularly those with diabetes and with known coronary anatomy who are proceeding to PCI, unless there is a high risk of life-threatening bleeding or other contraindications (COR: I, LOE: B). Clopidogrel is only recommended in patients for whom both ticagrelor and prasugrel are not an option (COR: I, LOE: A).