The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) together with the American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has released guidelines to organize recommendations on the basis of the current evidence for the diagnosis and management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The latest STEMI guidelines from the ESC were released in late 2012, followed closely by those of the ACCF-AHA in 2013. The 2 guidelines parallel each other in their recommendations, with notable variations worthy of discussion. This review aims to summarize key elements of these guidelines and the evidence supporting them with a focus on the important differences between the recommendations of the 2 groups.

Treatment Goals

Time to treatment

Rapid diagnosis and treatment of STEMI is a key aspect to improving care to patients. Reductions in the delay to treatment have repeatedly been shown to improve outcomes, and the recommendations are geared toward improving protocols to facilitate rapid therapy. A major priority is reducing the time from symptom onset to the first medical contact. The time delay for patients to seek medical care has historically been approximately 1.5 to 2 hours, and therefore, the guidelines emphasize the need for education in the community for patients to recognize symptoms early and seek appropriate help. The use of emergency transport is also paramount. According to the National Emergency Number Association, more than 98% of the US population is covered by 9-1-1 service, and there is an agreement that emergency medical services are underutilized in patients with signs and symptoms of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). There is a shift to include the first medical contact, whether it is the paramedic, nurse, or physician, as the reference time for diagnosis and treatment. Including paramedics in the diagnostic process and providing them with the ability to perform prehospital electrocardiograms can enable an earlier diagnosis of ST-segment elevation. Communications between the paramedics and the hospitals can direct the patient quickly to hospitals capable to perform primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with early notification of appropriate staff and, in turn, faster treatment times. A more aggressive approach to substantially reduce the time from the first medical contact to therapy would be to treat patients with fibrinolysis before hospital arrival. Indeed, the ESC guidelines provide a class IIa recommendation for prehospital fibrinolytic therapy, and the ACCF-AHA acknowledges the potential value of such an approach and emphasizes the need to evaluate the implementation of such protocols.

Impact of timing on decision making for reperfusion approach

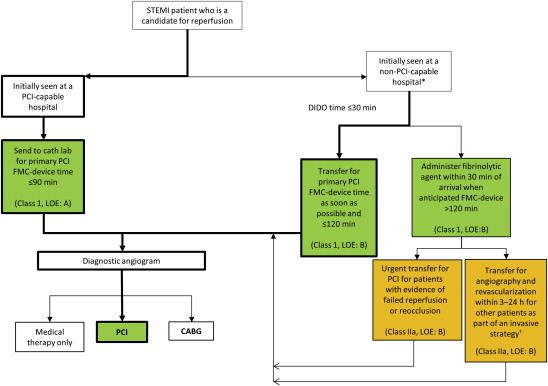

When patients arrive at a non–PCI-capable hospital, rapid decisions must be made regarding the type of reperfusion therapy, on the basis of the anticipated delay to PCI if a transfer occurs. Both the ESC and ACCF-AHA guidelines provide an algorithm on the basis of timing of presentation to guide the optimal choice for reperfusion therapy ( Figure 1 ). The survival benefit of PCI over fibrinolysis is negated when PCI is performed >120 minutes after presentation, and therefore, both guidelines state that if the anticipated delay to primary PCI is >120 minutes (i.e., presentation to a non–PCI-capable hospital without means for efficient transfer), a fibrinolytic agent should be administered. In early presenters and patients with a large area of myocardium at risk, the European guidelines decrease the acceptable time for delay to PCI to ≤90 minutes.

Primary PCI

Time from symptom onset

The preferred method for reperfusion of STEMI is primary PCI. The indications for primary PCI are based on timing from symptom onset and the clinical status of the patient. The strongest recommendation is for reperfusion within 12 hours of symptom onset. From the American perspective, the primary goal is to perform primary PCI within 90 minutes of the first medical contact. In the European guidelines, there is a preference for PCI within 60 minutes in primary PCI hospitals, with maximum delay of 90 minutes in these patients. The ACCF-AHA also adds a level IB recommendation for primary PCI within 12 hours in patients with contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy, regardless of the time delay from the first medical care. Severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock at any time after STEMI onset is an indication for primary PCI, therefore extending the acceptable treatment times for this group of patients. Beyond 12 hours from symptom onset, the recommendations for reperfusion are strong if the patients have continued ischemic symptoms, although the ESC suggests that PCI can be considered up to 24 hours in stable patients, although after 24 hours, reperfusion is not recommended (class III).

Access site

Radial access for angiography and PCI has gained substantial attention recently within the United States. The Radial Versus Femoral Access for Intervention trial (RIVAL) was a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of radial compared with femoral access in 7,021 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) treated with an early invasive approach and intended PCI. Although the primary results showed no difference in the rate of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or non–coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)-related bleeding between groups, subgroup analysis demonstrated reduced mortality in patients with STEMI who were randomly allocated to radial access. This exploratory and hypothesis-generating observation was subsequently confirmed in a dedicated STEMI trial, in which patients randomly assigned to radial access had a significantly lower rate of net adverse clinical events and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, including mortality. In RIVAL, there was a significant interaction between the benefit of radial access and operator experience, suggesting that the benefit of radial access depends on the radial expertise of the operators. Although according to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, the rate of radial access is increasing substantially in the United States, radial access is substantially more common in European countries than the United States, and the level of recommendation regarding access site in the ESC and ACCF-AHA guidelines in part reflects the rate of radial PCI in their respective regions. The ESC guidelines state that “if performed by an experienced radial operator, radial access should be preferred over femoral access” (class IIa, level of evidence B). In the United States, where radial access is less common and therefore less-experienced radial operators are the norm, the ACCF-AHA does not make any formal recommendations but acknowledges that radial access can decrease bleeding in experienced hands.

Technical aspects

Once it has been determined that the patient requires primary PCI, it is important to consider technical aspects of the procedure.

Nonculprit lesions

The data regarding intervention on noninfarct lesions are not consistent and indicate that there is potential for serious adverse cardiac events if undertaken. The ACCF-AHA states that PCI of a non–infarct-related artery should not be performed in stable patients because this is associated with worse outcomes (class III recommendation, harm). The ESC guidelines provide scenarios in which intervention in a nonculprit vessel may be considered, stating that primary PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel with the exception of cardiogenic shock and persistent ischemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion (class IIA, level of evidence B). Recent data supporting the safety of nonculprit PCI at the same setting of primary PCI may influence future guideline recommendations.

Type of stent

The use of stenting over angioplasty alone is a widely accepted practice, given its clinical efficacy; stent placement is a class I recommendation (level of evidence A) in the ACCF-AHA guidelines. The choice of the type of stent to implant in patients presenting for STEMI is a more nuanced situation. Use of a bare-metal stent (BMS) is preferred over use of drug-eluting stent (DES) in patients with contraindications to dual-antiplatelet therapy over the subsequent year, including patients with anticipated surgery or high bleeding risk. In addition, DES should be avoided in patients with potentially poor compliance with medication, as the risk of stent thrombosis in noncompliant patients is high. According to the ACCF-AHA guidelines, the use of a BMS in poorly compliant patients is a class I recommendation (level of evidence C, i.e., according to expert consensus), whereas it is a class IIa recommendation within the European guidelines.

Thrombus aspiration

Other nonpharmacologic interventions in patients with STEMI to deal with large intracoronary thrombus burden may also provide benefit. According to a recent meta-analysis, there is improved myocardial perfusion and favorable mortality outcomes at follow-up when aspiration is used. However, the outcomes of randomized clinical trials of manual aspiration have been inconsistent. Given this inconsistency, both European and American guidelines provide a class IIa recommendation for the use of aspiration thrombectomy. In specific, the ACCF-AHA guidelines state that “manual aspiration thrombectomy is reasonable for patients undergoing primary PCI” (level of evidence B), whereas the ESC guidelines recommend that routine thrombus aspiration be considered (level of evidence B).

Primary PCI

Time from symptom onset

The preferred method for reperfusion of STEMI is primary PCI. The indications for primary PCI are based on timing from symptom onset and the clinical status of the patient. The strongest recommendation is for reperfusion within 12 hours of symptom onset. From the American perspective, the primary goal is to perform primary PCI within 90 minutes of the first medical contact. In the European guidelines, there is a preference for PCI within 60 minutes in primary PCI hospitals, with maximum delay of 90 minutes in these patients. The ACCF-AHA also adds a level IB recommendation for primary PCI within 12 hours in patients with contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy, regardless of the time delay from the first medical care. Severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock at any time after STEMI onset is an indication for primary PCI, therefore extending the acceptable treatment times for this group of patients. Beyond 12 hours from symptom onset, the recommendations for reperfusion are strong if the patients have continued ischemic symptoms, although the ESC suggests that PCI can be considered up to 24 hours in stable patients, although after 24 hours, reperfusion is not recommended (class III).

Access site

Radial access for angiography and PCI has gained substantial attention recently within the United States. The Radial Versus Femoral Access for Intervention trial (RIVAL) was a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of radial compared with femoral access in 7,021 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) treated with an early invasive approach and intended PCI. Although the primary results showed no difference in the rate of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or non–coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)-related bleeding between groups, subgroup analysis demonstrated reduced mortality in patients with STEMI who were randomly allocated to radial access. This exploratory and hypothesis-generating observation was subsequently confirmed in a dedicated STEMI trial, in which patients randomly assigned to radial access had a significantly lower rate of net adverse clinical events and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, including mortality. In RIVAL, there was a significant interaction between the benefit of radial access and operator experience, suggesting that the benefit of radial access depends on the radial expertise of the operators. Although according to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, the rate of radial access is increasing substantially in the United States, radial access is substantially more common in European countries than the United States, and the level of recommendation regarding access site in the ESC and ACCF-AHA guidelines in part reflects the rate of radial PCI in their respective regions. The ESC guidelines state that “if performed by an experienced radial operator, radial access should be preferred over femoral access” (class IIa, level of evidence B). In the United States, where radial access is less common and therefore less-experienced radial operators are the norm, the ACCF-AHA does not make any formal recommendations but acknowledges that radial access can decrease bleeding in experienced hands.

Technical aspects

Once it has been determined that the patient requires primary PCI, it is important to consider technical aspects of the procedure.

Nonculprit lesions

The data regarding intervention on noninfarct lesions are not consistent and indicate that there is potential for serious adverse cardiac events if undertaken. The ACCF-AHA states that PCI of a non–infarct-related artery should not be performed in stable patients because this is associated with worse outcomes (class III recommendation, harm). The ESC guidelines provide scenarios in which intervention in a nonculprit vessel may be considered, stating that primary PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel with the exception of cardiogenic shock and persistent ischemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion (class IIA, level of evidence B). Recent data supporting the safety of nonculprit PCI at the same setting of primary PCI may influence future guideline recommendations.

Type of stent

The use of stenting over angioplasty alone is a widely accepted practice, given its clinical efficacy; stent placement is a class I recommendation (level of evidence A) in the ACCF-AHA guidelines. The choice of the type of stent to implant in patients presenting for STEMI is a more nuanced situation. Use of a bare-metal stent (BMS) is preferred over use of drug-eluting stent (DES) in patients with contraindications to dual-antiplatelet therapy over the subsequent year, including patients with anticipated surgery or high bleeding risk. In addition, DES should be avoided in patients with potentially poor compliance with medication, as the risk of stent thrombosis in noncompliant patients is high. According to the ACCF-AHA guidelines, the use of a BMS in poorly compliant patients is a class I recommendation (level of evidence C, i.e., according to expert consensus), whereas it is a class IIa recommendation within the European guidelines.

Thrombus aspiration

Other nonpharmacologic interventions in patients with STEMI to deal with large intracoronary thrombus burden may also provide benefit. According to a recent meta-analysis, there is improved myocardial perfusion and favorable mortality outcomes at follow-up when aspiration is used. However, the outcomes of randomized clinical trials of manual aspiration have been inconsistent. Given this inconsistency, both European and American guidelines provide a class IIa recommendation for the use of aspiration thrombectomy. In specific, the ACCF-AHA guidelines state that “manual aspiration thrombectomy is reasonable for patients undergoing primary PCI” (level of evidence B), whereas the ESC guidelines recommend that routine thrombus aspiration be considered (level of evidence B).

Antiplatelet Therapy

Antiplatelet therapy is a cornerstone of treatment in patients who underwent PCI for STEMI. An important addition to the most recent guidelines is the introduction of the new P2Y 12 inhibitors, ticagrelor and prasugrel. The 2 writing committees integrate the 3 antiplatelet agents—clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel—slightly differently into their recommendations, as the European guidelines provide specific preferences among the 3 P2Y 12 inhibitors on the basis of a given patient’s clinical presentation, risk factors, and previous therapy, whereas the American guidelines (summarized in Table 1 ) do not state a particular preference for drug selection. Use of P2Y 12 inhibitors is an ACCF-AHA class I recommendation, with loading as early as possible or at the time of PCI and continuation of maintenance dose for 1 year thereafter regardless of stent type. Continued therapy beyond 1 year can be considered; however, this is a lower, Class IIb recommendation. The results of the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy trial (DAPT; clinicaltrials.gov identifier, NCT00977938 ) will likely influence future guideline recommendations regarding the continuation of antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year in patients receiving DES during primary PCI. Early discontinuation of P2Y 12 inhibitor is suggested only in appropriate clinical scenarios and evaluating the balance of bleeding and thrombotic risk after discussion with the interventional cardiologist.