Ultrasound for Vascular Cannulation

Solomon Aronson1

Katherine A. Grichnik2

Solomon Aronson2

1OUTLINE AUTHOR

2ORIGINAL CHAPTER AUTHORS

I. INTRODUCTION

Although the procedure of placing a central venous catheter (CVC) was first identified in 1952 for use in military casualty fluid resuscitation, it did not become commonly used until the late 1960s. The introduction of total parenteral nutrition increased CVC use, and it has since become a common procedure with broad use for temporary vascular access requiring fluid administration, medications, chemotherapy, total parenteral nutrition, hemodialysis and to assess hemodynamic parameters as well as occasionally in patients with a need for frequent phlebotomy. Currently over 3 million CVCs are placed annually.

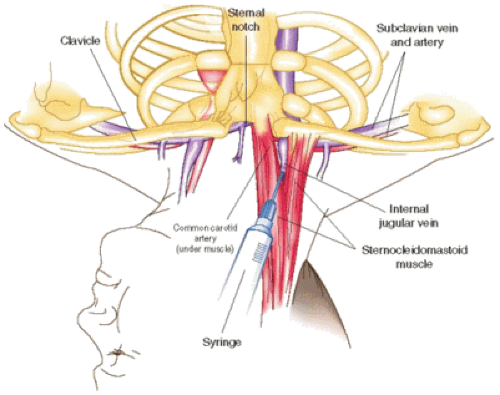

Landmark-based techniques for central access have been characterized as inexpensive and efficient1,2,3,4,5; however, there remains up to a 40% complication rate with this technique (Fig. 17-1).

Anatomy underlies the success or failure of these techniques with anomalies in vascular structure, vessel position, patient’s movement, and other proximal structures of the perivascular area critical. Common complications for central venous access include accidental arterial puncture, hematoma, pneumothorax,6,7 and even death.8 Serious bleeding-related consequences of accidental arterial puncture include hematoma of the neck and hematoma of the mediastinum or hemothorax. There are also possibilities of potential damage to the cervicothoracic ganglion (stellate ganglion), phrenic nerves, and other important nerves described.9,10,11

II. TECHNIQUES

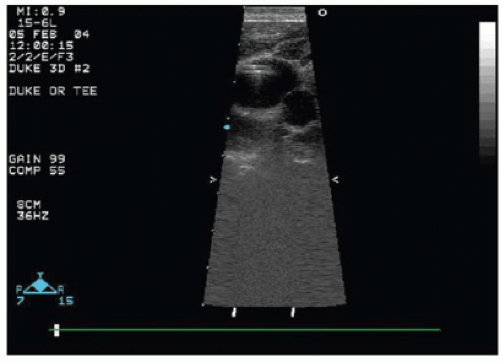

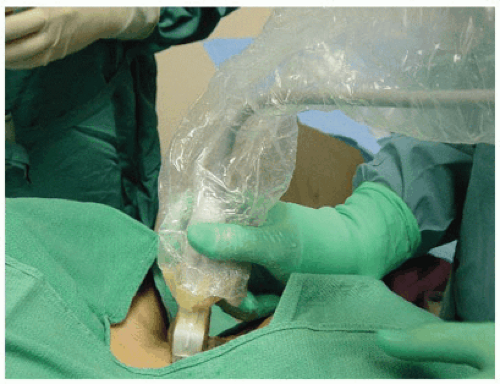

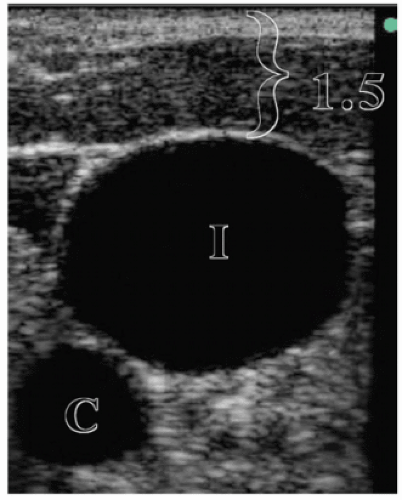

The desired vein and surrounding anatomic structures can be visualized prior to or during insertion of the needle, guidewire, and catheter. One technique is to use an ultrasound (US) probe to first locate the vein, measure its depth beneath the skin, and then proceed as usual with sterile needle placement. A second technique is to image the great vessels during cannulation with sterile sheath over US probe (Figs. 17-3 and 17-4).

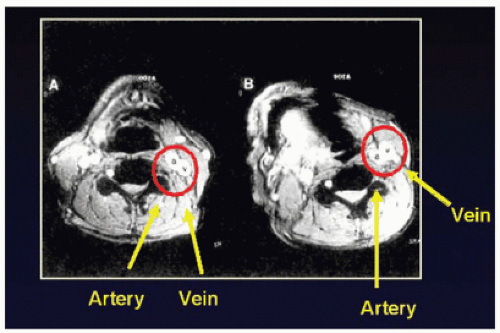

Scans of the vessels can be longitudinal or cross-sectional. Similarly, needle insertion can be performed in either longitudinal or transverse relation

to the US probe with the choice of axis depending on the location of the vessel, operator experience, and anatomic relationships. A cross-sectional scan is commonly used for the internal jugular vein (IJV). Puncturing a vessel in a cross-sectional image with transverse needle placement demonstrates a hyperechogenic signal with the needle in perpendicular axis to

the US beam. Ideally, this “echogenic” is the tip of the needle and not the shaft; however, it may be difficult for the operator to differentiate where the end of the needle actually is placed. Blaivas et al.12 nevertheless reported that the transverse, short-axis view of the needle in vascular access was easier for novices to learn than a technique using longitudinal scan (Figs. 17-5, 17-6, 17-7 and 17-8).

to the US probe with the choice of axis depending on the location of the vessel, operator experience, and anatomic relationships. A cross-sectional scan is commonly used for the internal jugular vein (IJV). Puncturing a vessel in a cross-sectional image with transverse needle placement demonstrates a hyperechogenic signal with the needle in perpendicular axis to

the US beam. Ideally, this “echogenic” is the tip of the needle and not the shaft; however, it may be difficult for the operator to differentiate where the end of the needle actually is placed. Blaivas et al.12 nevertheless reported that the transverse, short-axis view of the needle in vascular access was easier for novices to learn than a technique using longitudinal scan (Figs. 17-5, 17-6, 17-7 and 17-8).

Doppler US may additionally be used for guidance with an audio signal, fingertip pulsed Doppler, or a probe within the seeking needle.13,14

▪ FIGURE 17.4 A technique to image the great vessels during cannulation with sterile sheath over US probe. |

III. RATIONALE

Location and successful cannulation of the IJV with US depend on a number of factors, including the size of the IJV, intravascular volume status, and the degree of pressure exerted by the US probe on the patient. Head rotation and patient positioning are further factors influencing the procedure of cannulation and US detection.15,16 Anatomic variation and IJV occlusion based on US examinations13,14,17,18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree