Tumors and Other Mass Lesions

Although cardiac tumors can often be seen on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), their location, size, and relation to surrounding structures are better defined by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE).

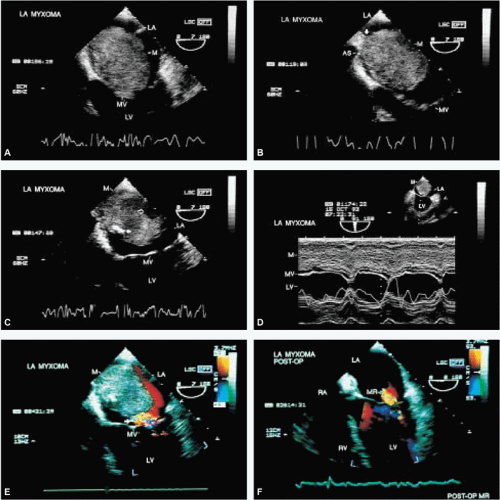

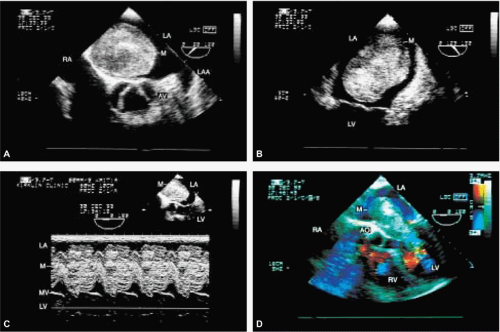

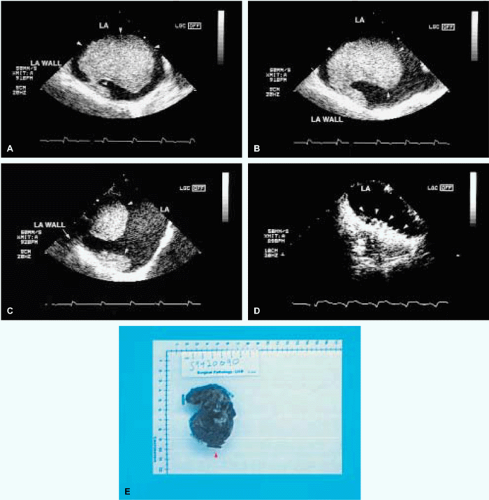

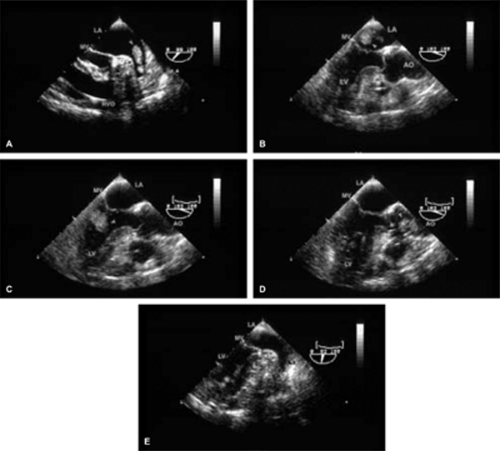

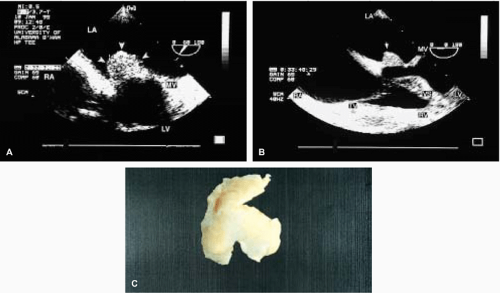

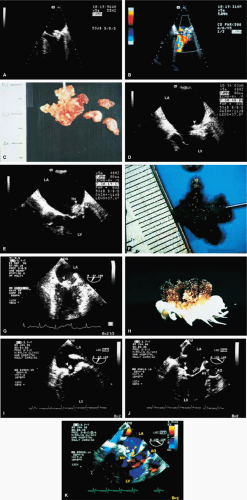

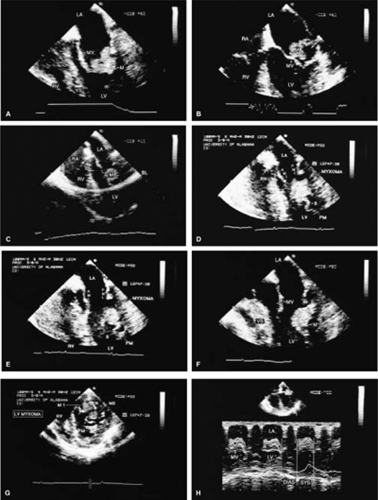

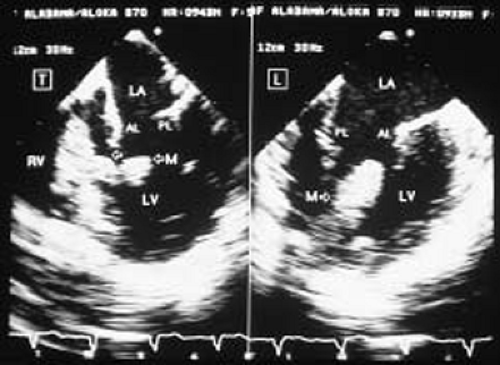

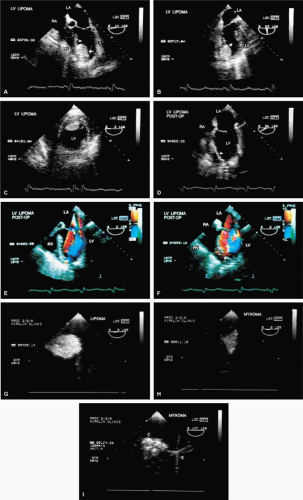

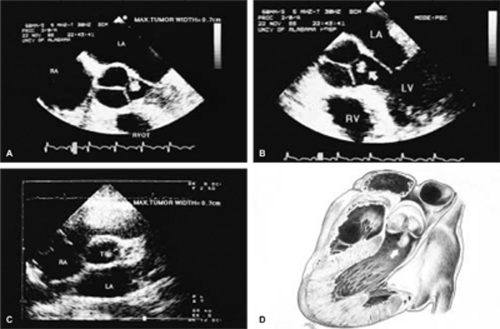

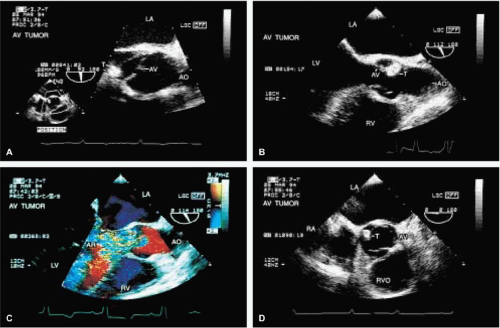

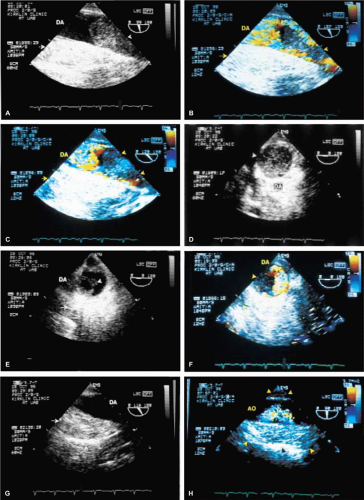

The most common primary cardiac tumor is the myxoma. This tumor rarely metastasizes, but it can cause obstruction and frequently embolize, making its immediate removal mandatory. These tumors can also cause regurgitation by interfering with valve function, and they can cause a variety of constitutional symptoms. Myxomas are usually solitary and are located most commonly in the left atrium. However, because they can occur in any chamber and may be multiple, a careful transesophageal echocardiographic investigation of all the cardiac chambers should be conducted preoperatively to be certain that all tumors have been detected and are removed. Myxomas characteristically have cystic spaces caused by hemorrhages and areas of calcification. The base of the tumor may be either broad or narrow, and a careful search should be made for the attachment point. In one patient we studied there was massive calcification that involved the left atrial free wall and protruded into the left atrial cavity, mimicking a myxoma. Heavy mitral annular calcification may also produce a confusing picture, especially if some areas are soft and mobile. Lipomas are characteristically more refractile than a noncalcified myxoma, which may help in distinguishing between them. Tumors such as a leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma may arise from the wall of a blood vessel and cause obstruction to blood flow. Fibroelastomas often present as irregular mobile masses on valves or chamber walls, emanating from narrow stalks. Because of their embolic potential they should be surgically removed. Large mobile vegetations attached to valves may mimic fibroelastoma or a small myxoma on a valve, but the associated clinical picture, which is suggestive of infective endocarditis, helps in differentiating between them. They must be distinguished from Lambl’s excrescences, which are a normal finding in many adults. These are filamentous mobile avascular structures that generally arise at the line of closure of valves and are common in adults. Fibroelastomas are not as thin as Lambl’s excrescences and, unlike Lambl’s excrescences, they do not arise from the line of closure, but from elsewhere on the valve. Myxomatous thickening or nodules involving the mitral valve may also simulate a small tumor.

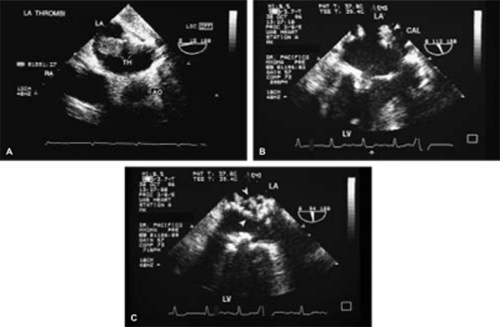

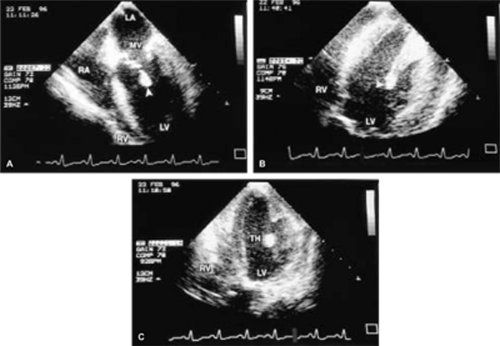

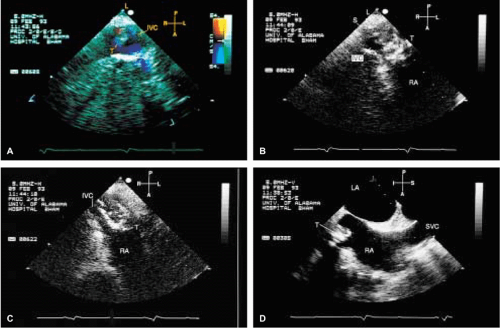

Thrombus can mimic a tumor, and the distinction often cannot be made by echocardiography. As with tumors, identifying the point of attachment is important in surgical planning. Although low-flow velocities are often present (and are, indeed, causative) when a thrombus is found, this may not always be the case, and thrombi can occur in the absence of an identifiable precipitating factor. TEE is more sensitive than TTE for the detection of thrombi, particularly in the atrial appendages. Thrombi are generally broad based, rather than pedunculated, and are hyperechoic relative to the myocardium except that there tends to be an echolucent interface between the thrombus and the atrium. This echolucent interface may be used to try to differentiate the thrombus from the tumor, but from a practical point of view, echocardiographic differentiation of the tumor from the thrombus is frequently not feasible.

Thrombi originating in the heart are most often, but not invariably, associated with low-flow regions. In the left ventricle, thrombi commonly attach to hypokinetic or akinetic wall regions, ventricular aneurysms, or occur in the setting of cardiomyopathy.

In the left atrium, thrombus can occur anywhere, but most commonly arises in the left atrial appendage, which is far better imaged with TEE than with TTE. On TEE, the left atrial appendage thrombus must be differentiated from the pectinate muscles and from septa between multiple lobes that not infrequently make up the left atrial appendage. Spontaneous contrast, which occurs characteristically with slow flow, is caused by red blood cell aggregation and is a risk factor for the development of thrombus.

When thrombi originate in the right atrium, indwelling catheters or pacemaker leads are frequently

the cause, although migrating emboli from lower extremity veins are occasionally visualized. Interestingly, during transesophageal examination we have visualized thrombi, subsequently confirmed by both surgery and pathology, attached to the mitral valve and in the region of papillary muscles in the normally functioning left and right ventricles, with no clinically or echocardiographically discernible cause. Right-sided tumors must be differentiated from normal structures such as hypertrophied trabeculations in the right atrium or right ventricle and prominent or hypertrophied right ventricular papillary muscles. A prominent eustachian or thebesian valve and Chiari network, as well as a prominent crista terminalis visualized at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium, may also be mistaken for a tumor mass. Abnormal thickening of normal structures, such as lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum or nonspecific thickening of the “Q-tip” (i.e., left atrial wall invagination or infolding separating the appendage from the left upper pulmonary vein) also may mimic tumor infiltration.

the cause, although migrating emboli from lower extremity veins are occasionally visualized. Interestingly, during transesophageal examination we have visualized thrombi, subsequently confirmed by both surgery and pathology, attached to the mitral valve and in the region of papillary muscles in the normally functioning left and right ventricles, with no clinically or echocardiographically discernible cause. Right-sided tumors must be differentiated from normal structures such as hypertrophied trabeculations in the right atrium or right ventricle and prominent or hypertrophied right ventricular papillary muscles. A prominent eustachian or thebesian valve and Chiari network, as well as a prominent crista terminalis visualized at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium, may also be mistaken for a tumor mass. Abnormal thickening of normal structures, such as lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum or nonspecific thickening of the “Q-tip” (i.e., left atrial wall invagination or infolding separating the appendage from the left upper pulmonary vein) also may mimic tumor infiltration.

Malignant tumors of the heart are unusual but, when present, they tend to metastasize early. They can often be recognized on the basis of the fact that they deform the walls of the heart. Other tumors, such as melanoma, may produce blood-borne metastases in the heart. Mediastinal tumors such as a leiomyosarcoma may compress or invade the heart, either directly or through vascular accesses such as the pulmonary veins. Because these tumors are vascular, multiple small blood vessels may be imaged within the tumor by color Doppler, especially if the Nyquist limit is kept low. Sclerosing mediastinitis producing narrowing of the systemic and pulmonary veins at their junction with the heart may simulate an extracardiac tumor. Postoperative hematomas also must be differentiated from extracardiac tumor masses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree