Tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infective granulomatous disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one-third of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and TB accounts for over 3 million deaths throughout the world per year. Multi-drug resistant TB (resistance to at least rifampicin and isoniazid) is an international problem with approximate prevalence rates for new cases of TB of around 1% but for patients with prior treatment for TB they are at around 9%. In certain regions, e.g. in Iran, rates >50% have been reported.

In order to reduce the spread of disease, there has been a focus on treating active TB and on rigorous contact tracing. In addition, due to poor treatment completion rates, supervision of therapy has been considered important. However, the evidence base suggests that supervised therapy is not a universal requirement but should be focused on groups at high risk of nonadherence to treatment, such as patients that abuse alcohol.

This section on TB, with illustrative radiology, microbiology, and pathology, discusses the investigation, diagnosis, and management of TB. Key areas covered include primary TB, post-primary TB with a particular focus on pulmonary, pleural, and mediastinal lymph node TB, multi-drug resistant TB, and mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis (MOTT). The final section deals with TB long-term sequelae.

Aetiology

Tuberculosis is due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, which includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, and M. microti. In humans, M. tuberculosis remains the predominant pathogen. There are many risk factors for the development of TB, including:

Contact with an infectious case of tuberculosis (adolescents, young adults, and the elderly are particularly at risk).

Nonwhite ethnic groups, in particular black African and Indian subcontinent.

Recent immigration from a country with a high prevalence of TB within the last 5 years.

Malnutrition.

Alcoholism.

Social deprivation.

Immunosuppression, in particular HIV infection and immunosuppression related to drug treatment (e.g. corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and TNF alphablockers such as infliximab).

Diseases with impaired cell-mediated immunity such as lymphoma or leukaemia.

Co-morbid illness such as diabetes, chronic renal failure, gastrectomy.

Solid organ transplantation.

Cancer.

Silicosis.

Old TB on the chest radiograph.

Primary tuberculosis

Primary TB refers to the first exposure, usually in a child or young adult with no specific immunity. The majority (>90%) of patients are asymptomatic. The chest radiograph shows consolidation usually in the mid or lower zones (Ghon focus), although any lobe can be affected. This is usually associated with ipsilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and is termed the primary complex. Prior to the cellmediated immunity there is haematogenous and lymphatic spread. Cell-mediated immunity occurs within a 3 week to 2 month period. Healing occurs within 6 months, occasionally leaving a small calcified or fibrotic scar and sometimes calcified hilar glands. There is an approximately 10% lifetime risk for the development of active TB (5% within the first 2 years and 5% usually later in life).

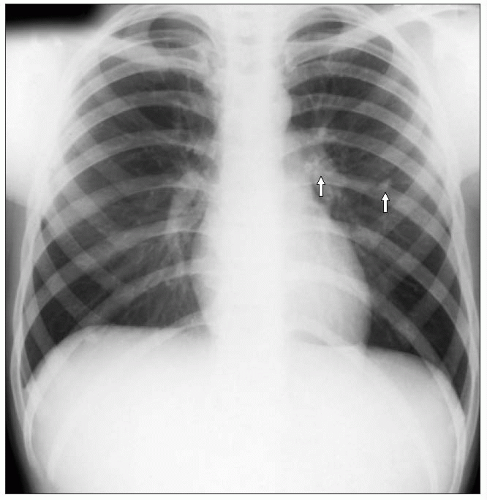

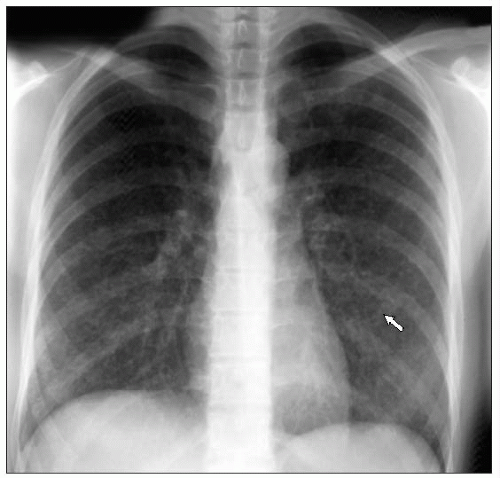

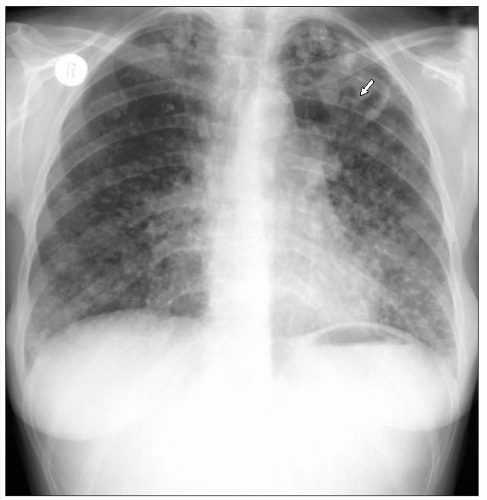

4.1A Chest radiograph showing a primary complex with left mid zone consolidation and associated left hilar lymphadenopathy, due to primary TB (arrows). (Courtesy of Dr. A. Wightman, Consultant Radiologist, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, Scotland.) |

Illustrative cases

Figure 4.1A shows a chest radiograph demonstrating a primary complex with left mid zone consolidation (Ghon focus) and associated left hilar lymphadenopathy. Figure 4.1B shows a chest radiograph taken 6 months following resolution of the primary complex. Note the calcified left mid zone Ghon focus and calcified left hilar glands.

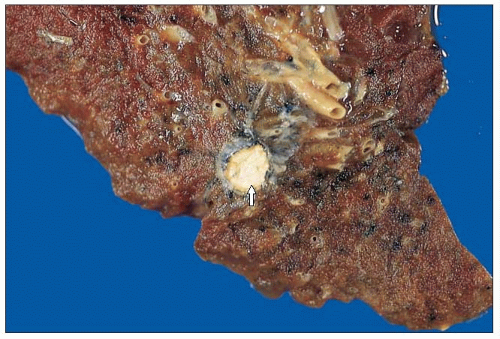

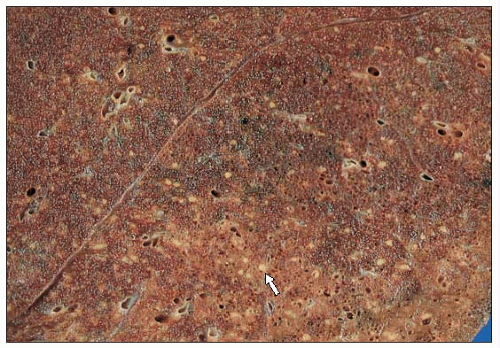

Figure 4.2 is a macroscopic picture of a pulmonary resection specimen showing a rounded calcified nodule in the lung parenchyma. No evidence of granulomatous inflammation was identified histologically and the appearance is typical of that seen with a healed primary tuberculous infection with subsequent calcification (Ghon focus). These lesions may be seen incidentally on chest radiographs or be identified in pulmonary resection specimens performed for lung cancer. The term ‘tuberculoma’ is sometimes applied to solitary rounded lesions in the lung which may mimic the appearances of lung cancer. These lesions may be composed of fibrous scars representing old, inactive TB or show features suggesting some residual active infection.

Complications of primary TB

Complications of primary TB include the following:

Erythema nodosum.

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis.

Progressive pulmonary disease.

Tuberculoma (a small isolated rounded shadow or a shadow associated with a minimal adjacent infiltration), representing either active or inactive disease. In active disease the histology reveals a mass of granulomas with central caseation and scanty TB organisms may be seen. In inactive disease the lesion is predominantly hyalinized. One of the main concerns is that it is mass-like and often thought to be a primary lung cancer.

Atelectasis from bronchial obstruction because of enlarged lymph nodes.

Pleural or pericardial effusion.

Miliary TB.

Meningitis.

Broncholith.

4.3 Chest radiograph showing diffuse nodules particularly noticeable in the intercostal spaces due to miliary TB (arrow). |

Illustrative cases

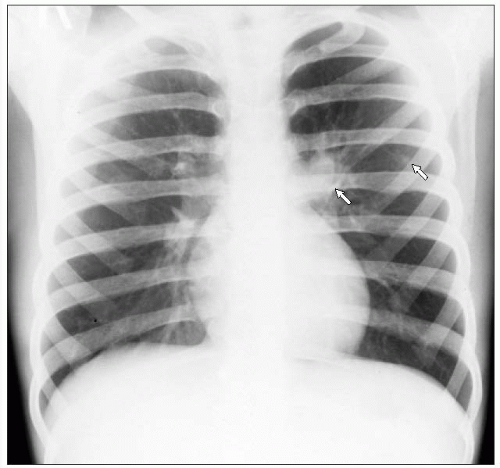

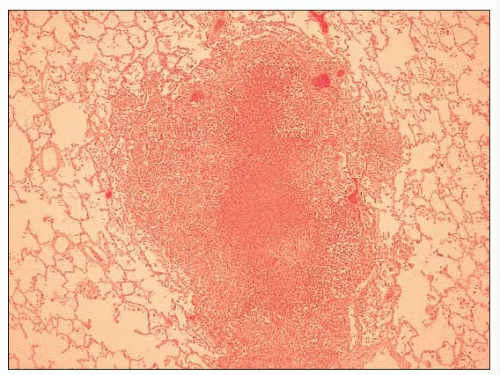

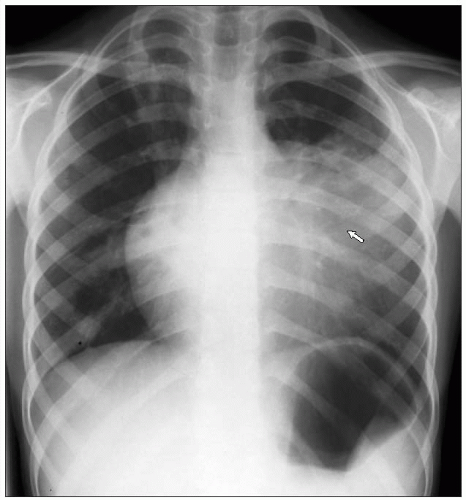

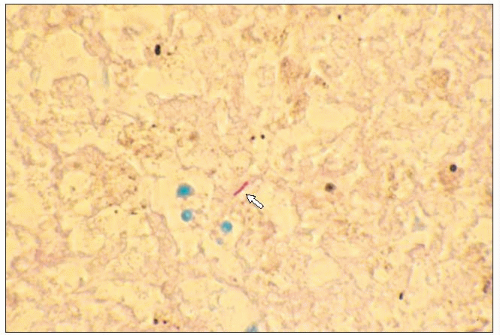

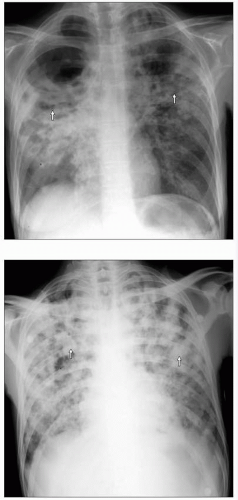

Figures 4.3,4.4,4.5,4.6 present chest radiographs and pathology from patients with miliary TB. The chest radiographs (4.3, 4.4) show features of miliary tuberculosis with <5 mm diffuse nodules throughout the lung fields. These are particularly noticeable in the intercostal spaces. Figure 4.5 is a macroscopic picture of a lung specimen from a patient with miliary TB. It shows the presence of numerous small pale nodules on the cut surface, measuring a few millimetres in diameter. Figure 4.6 is a photomicrograph of the specimen shown in 4.5. It demonstrates small nodular areas of inflammation in the lung parenchyma with necrotic centres. The necrotic debris is surrounded predominantly by macrophages. Well developed granulomas and giant cells are usually less obvious in miliary TB. Organisms are, however, more frequently seen with Ziehl-Neelsen stains than in the more typical fibrocaseous tuberculous infection, where much of the pathological process identified is the result of a hypersensitivity reaction.

The chest radiograph in 4.7 is from a 9-year-old girl and shows active TB in the lingula, presumed to be due to progression from a primary lesion that has not healed. Note the loss of definition of the left heart border in keeping with disease affecting the lingula.

4.4 Chest radiograph showing diffuse nodules particularly noticeable in the intercostal spaces due to miliary TB (arrow). |

4.5 Macroscopic pictures of lung tissue showing diffuse pale nodules, due to miliary TB (arrow). |

4.6 Photomicrograph of the specimen in 4.5 demonstrating small nodular inflammatory areas with necrotic centres, due to miliary TB. |

4.7 Chest radiograph showing active TB in the lingula (arrow). |

Post-primary TB

Post-primary TB follows direct progression of a primary lesion, endogenous reactivation of quiescent primary or postprimary lesion, or exogenous reinfection. Pulmonary TB remains the commonest form in both HIV-positive and HIVnegative patients. Extrapulmonary TB is less common but more prevalent in HIV-positive patients. In extrapulmonary TB, the lymph nodes, pleura, and bones/joints are the most common sites to be affected.

Illustrative cases

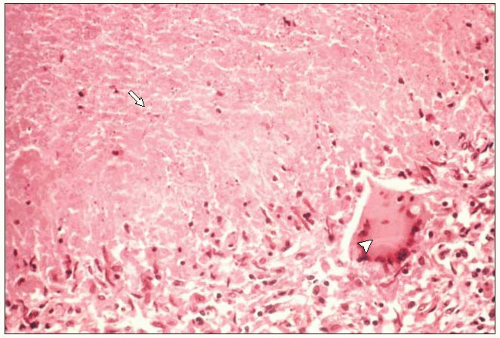

A macroscopic picture of a pulmonary resection specimen is shown in 4.8, and demonstrates the typical appearance of fibrocaseous TB. The lung contains a relatively well circumscribed grey mass, showing some cavitation and indrawing of the overlying pleura due to fibrosis within the lung parenchyma. The photomicrograph (4.9) shows caseous granulomatous inflammation. Amorphous eosinophilic necrotic debris is bounded by an inflammatory cell infiltrate composed predominantly of macrophages with admixed Langhan’s-type giant cells. Granulomatous inflammation in the lung may be seen in a wide range of conditions including sarcoidosis, extrinsic allergic alveoltitis, and vasculitis. Granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis, however, is usually indicative of an infective aetiology with mycobacteria or fungi, such as histoplasma.

Presentation of post-primary TB

The majority of patients with post-primary TB present after feeling unwell for several weeks to several months. Patients often present with a new cough (sometimes productive with or without haemoptysis), usually associated with symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, and general malaise. Patients with pleural TB may, in addition, have pleurisy and breathlessness. Patients with mediastinal lymph node TB may present only with fever, weight loss, night sweats, and general malaise.

4.8 Macroscopic picture of a pulmonary resection specimen with a grey mass showing focal cavitation and fibrosis typical of fibrocaseous TB (arrow). |

4.9 Photomicrograph of lung tissue demonstrating caseous granulomatous inflammation, due to active TB (arrow, caseous necrosis; arrowhead, giant cell). |

4.10 Ziehl-Neelsen stain of lung tissue from a patient with active TB, showing a rod-shaped mycobacterium (arrow). |

Investigations

Radiology

Active TB

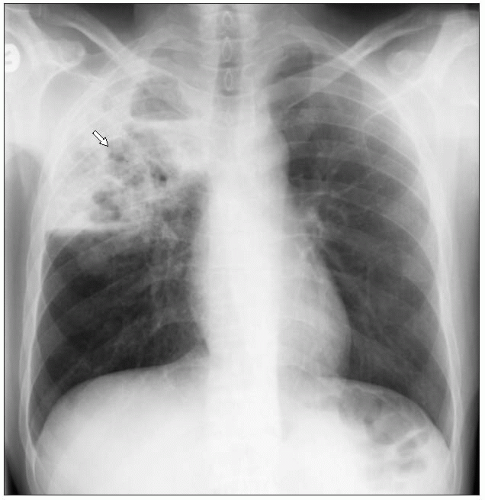

The chest radiograph is an essential first line investigation in patients suspected of having respiratory TB (pulmonary, pleural, or mediastinal lymph node sites). Patients with active respiratory TB will have an abnormal chest radiograph. Active pulmonary TB typically presents in the upper lobes, and can be unilateral or bilateral. The posterior and apical segments are the commonest sites to be affected. There can be widespread changes involving all lobes in extensive disease. Active TB is suggested if there is consolidation, nodular infiltration, and cavitation. Although these changes should alert the clinician to suspect TB, these appearances are not specific for TB, and other conditions, e.g. pneumonia and sarcoidosis, can present similarly.

4.11 Chest radiograph showing right upper lobe consolidation, infiltration, and cavitation confirmed to be of active TB (arrow). |

Illustrative cases

Figures 4.11,4.12,4.13 show chest radiographs from patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Note the infiltration, consolidation, and cavitation that should always alert the clinician to suspect active TB. The patient in 4.11 had unilateral disease in the right upper lobe. The patients in 4.12 and 4.13 had bilateral disease; these patients are usually systemically unwell and are often cachectic.

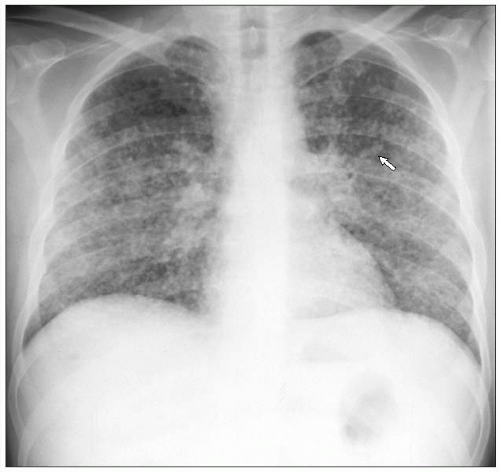

The radiographic changes due to active respiratory TB in HIV-positive patients can vary depending on the severity of the HIV disease. Patients with early HIV disease will have a typical presentation similar to non-HIV patients. In advanced HIV disease, patients often have atypical presentations: the changes on the chest radiograph can present in atypical sites such as the lower zones; patients may present with diffuse consolidation, and cavitation is less frequent, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is more frequent. Figures 4.14,4.15,4.16 present chest radiographs from HIV-positive patients with active pulmonary TB.

4.12, 4.13 Chest radiographs showing bilateral consolidation, infiltration, and cavitation, due to active TB (arrows). |

A chest radiograph of a 45-year-old female with extensive bilateral bronchopneumonia due to TB is shown in 4.14. Note the widespread nodular shadowing with cavitation in the left upper lobe. The patient was subsequently proven to be HIV-positive.

Figure 4.15 is a chest radiograph from a 40-year-old male with advanced HIV disease (he was not on antiretroviral therapy). There was minor consolidation without cavitation in the right mid zone. This patient was smear- and culturepositive for M. tuberculosis.

The chest radiograph shown in 4.16 is from an HIVpositive patient and shows right lower lobe consolidation without cavitation. This was confirmed to be due to M. tuberculosis from bronchoalveolar lavage samples.

Miliary, mediastinal and lymph node TB

In patients with miliary, pleural, and mediastinal lymph node TB, radiographic changes may be specific to the type of TB. Chest radiographs from patients with miliary tuberculosis reflect the inadequacy of the host defences in containing the tuberculous infection. The chest radiograph is grossly abnormal with diffuse miliary change, defined as <5 mm nodules that appear widespread (see 4.3, 4.4).

4.14 Chest radiograph showing widespread nodular shadowing with cavitation (arrow), due to active TB in an HIV-positive patient. (Courtesy of Dr. Ramage and Dr. Patel, Department of Radiology, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, Scotland.) |

In pleural TB, there is usually a unilateral pleural effusion and there may or may not be associated parenchymal lung abnormalities. Commonly, patients with mediastinal lymph node TB present with mediastinal lymphadenopathy alone. Figures 4.17,4.18,4.19,4.20 present chest radiographs from patients with pleural and mediastinal lymph node TB.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree