Tricuspid Valve Disease, Pulmonary Valve Disease, and Drug-Induced Valve Disease

Shikhar Agarwal

Brian P. Griffin

TRICUSPID VALVE DISEASE

I. INTRODUCTION.

The tricuspid valve (TV) apparatus consists of three valve leaflets septal, anterior, and posterior-along with the tricuspid annulus, the chordae tendineae, and the papillary muscles. Normally, the TV has an orifice area of 5 to 7 cm2. The normal TV annulus is an elliptical and nonplanar structure, lying somewhat inferiorly and anterolaterally compared with the mitral valve (MV) annulus. The noncircularity and the nonplanarity of the TV have important mechanistic and therapeutic implications for correction of TV anomalies. Both tricuspid stenosis (TS) and tricuspid regurgitation (TR) can produce typical symptoms of right-sided congestive heart failure in their advanced stages. TV dysfunction can occur in both anatomically normal and abnormal valves.

II. TRICUSPID STENOSIS (TS).

TS is rare as an isolated entity and is most commonly part of a multivalvular process. TS is usually organic in nature and is commonly encountered in conjunction with TR.

A. Etiology.

Table 17.1 lists the causes of TS.

1. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) by far is the most common cause of TS, accounting for > 90% of cases. Isolated TS is uncommon in these patients, and most patients have a combination of TS and TR. A large majority of patients with rheumatic TS have concurrent MV and aortic valve involvement. Clinically significant TV anomaly is present in only 5% of patients with RHD. Rheumatic TS is characterized by thickening and fibrosis of the valve leaflets, eventually culminating in marked leaflet contracture and commissural fusion.

2. Carcinoid heart disease is encountered in the setting of primary intestinal carcinoid tumors with secondary metastatic spread to the liver. Once metastatic to the liver, this neuroendocrine malignancy secretes numerous vasoactive substances (e.g., serotonin, histamine, and bradykinin), which directly affect the right-sided heart valves. Carcinoid valvular disease is characterized by thickened, retracted, shortened, and even fixed tricuspid leaflets, causing a mixed picture of regurgitation and stenosis. The pulmonic valve may also be involved. Unless there is a significant right-to-left shunt (via an atrial septal defect or patent foramen ovale), the left-sided heart valves are usually spared, owing to the clearance of vasoactive substances by the lungs.

B. Pathophysiology

1. TS produces a diastolic pressure gradient between the right atrium and the right ventricle, which is augmented when transvalvular flow increases. Therefore, the pressure gradient increases during inspiration or exercise and decreases during expiration. This typically occurs once the valve area falls below 1.5 cm2.

2. A modest elevation of mean diastolic pressure gradient (i.e., =5 mm Hg) can raise right atrial pressure (RAP) (i.e., > 10 mm Hg) sufficiently to produce signs of systemic venous congestion, including hepatomegaly, ascites, and edema.

3. The right atrial a wave may be very prominent and may approach the level of the right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP).

4. Resting cardiac output may be markedly reduced and may fail to augment with exercise, due to limited right ventricular preload.

5. Development of atrial fibrillation may result in higher RAPs due to the absence of organized atrial contraction and emptying.

C. Clinical presentation

1. Signs and symptoms. The presentation of TS varies depending on the severity of stenosis, the presence of concomitant cardiac lesions, and the etiology of the valvular disease.

a. Fatigue is common and related to low and relatively fixed cardiac output.

TABLE 17.1 Causes of Tricuspid Stenosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

b. Right upper quadrant pain can result from high systemic venous pressure and concomitant hepatomegaly, ascites, and abdominal distention.

c. Occasionally, patients will experience a fluttering discomfort in the neck, caused by the giant a waves transmitted to the jugular veins.

d. Severe TS may mask the typical symptoms of other coexisting valvular lesions, such as mitral stenosis (MS). In the case of MS, the flow limitation across the TV can minimize the pulmonary congestion, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea usually associated with MS.

2. Physical findings. The diagnosis of TS is often missed without a high index of suspicion. Clues that should raise suspicion of TS include the presence of elevated jugular venous pressure and accentuation of a diastolic murmur along the left sternal border with inspiration (not present in MS).

a. Elevated central venous pressure may lead to marked hepatomegaly, ascites, and peripheral edema. In sinus rhythm, a giant a wave in the jugular venous pulse at the first heart sound (S1) results from impaired right atrial diastolic filling during atrial systole.

b. Diastolic murmur. The murmur of TS is low pitched, diastolic, and best heard along the left lower sternal border in the third to fourth intercostal space or over the xiphoid process. If the rhythm is sinus, the murmur is prominent at end diastole (presystole). The low-pitched diastolic murmur may be obscured by the usually associated MS murmur. Accentuation of the murmur intensity with inspiration (Rivero-Carvallo sign) or other preload augmenting maneuvers (e.g., leg raising and squatting) may serve to differentiate the two murmurs or at least identify a component of TS in the setting of concurrent MS.

c. An opening snap (OS) may be heard at the left lower sternal border; however, this can be difficult to auscultate due to the commonly coexistent mitral OS.

d. Despite elevated neck veins and venous congestion, the patient may be comfortable lying flat due to the absence of pulmonary congestion. This apparent discrepancy between the severity of peripheral edema and the paucity of pulmonary congestion can help discriminate and identify TS from other valvular lesions.

e. Respiratory variation in splitting of the second heart sound (S2) may be absent in patients with TS due to the relatively fixed diastolic filling of the right ventricle despite respiration.

f. In patients with the carcinoid syndrome, symptoms related to neurohormonal release, such as flushing and diarrhea, are typically more common than symptoms attributable to TS.

D. Diagnostic testing. The hemodynamic expression of TS is a pressure gradient across the TV in diastole. A mean diastolic pressure gradient of 2 mm Hg across the TV establishes the diagnosis of TS during catheterization. Nowadays, hemodynamic diagnosis is rarely required, as the diagnosis is usually apparent on Doppler echocardiography.

1. Electrocardiogram (ECG). TS is suggested by the presence of right atrial enlargement on the ECG (P-wave amplitude > 2.5 mV in lead II). Because of the common coexistence of MS, biatrial enlargement may be seen.

2. Two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography. The echocardiogram is the most useful tool in identifying TS. Typical findings include reduction in the diameter of the TV orifice and thickening and diastolic doming of the tricuspid leaflets (especially the anterior leaflet). Doppler interrogation of the TV will reveal increased transvalvular velocity; a mean pressure gradient > 5 mm Hg using continuous-wave (CW) Doppler is generally diagnostic of TS. Although it is possible to estimate the TV area by pressure half-time or planimetry, such measurements have limited utility in practice, as the severity of TS is more commonly described by the tricuspid diastolic pressure gradient. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is generally less useful than transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) for assessing transvalvular gradients in TS, given that the TV is an anterior structure.

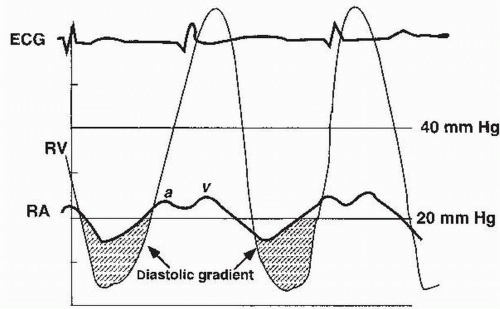

FIGURE 17.1 Tracings of simultaneous right atrial (RA) and right ventricular (RV) pressure waveforms in a patient with tricuspid stenosis. |

3. Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography. Given the complex 3D structure of the TV, 3D echocardiography (transthoracic or transesophageal) may prove to be a useful adjunct to standard 2D echocardiography. Using this modality, all TV leaflets can be simultaneously imaged, potentially allowing for more accurate calculation of TV area and precise visualization of leaflet motion.

4. Given the accuracy of modern echocardiographic techniques, cardiac catheterization can often be bypassed. Right heart catheterization can be used to confirm the diagnosis already suggested by Doppler echocardiography and can serve as a prelude to therapeutic balloon valvuloplasty. Cardiac output is typically low. The RAP is elevated and the a wave may be very tall, sometimes approaching the RVSP in magnitude. Simultaneous measurement of the right atrial and right ventricular pressures with dual catheters (or a dual-lumen catheter) enables the calculation of the diastolic pressure gradient (Fig. 17.1). The measured gradient is highly dependent on cardiac output and heart rate. Maneuvers such as lifting the legs or administration of atropine may accentuate the gradient.

E. Therapy

1. Medical therapy consists of intensive sodium restriction and diuretics.

2. Defining coexisting valvular lesions is critical to properly managing TS. For instance, in patients with combined TS and MS, the former should not be corrected alone, as this may produce pulmonary congestion. If other valvular surgery is planned, concomitant treatment of TS should be considered if the gradient exceeds 5 mm Hg or the TV orifice area is < 2.0 cm2.

3. Severe stenosis requires balloon valvuloplasty or TV replacement. The indications for surgery or balloon valvuloplasty are usually determined by the severity of concomitant mitral or aortic valve disease. Limiting symptoms due to predominant TS are considered an indication for valvuloplasty or surgery. Balloon valvuloplasty appears to be successful from both a symptomatic and a hemodynamic standpoint, but can result in significant TR, potentially necessitating valve replacement.

4. Bioprostheses are favored when valve replacement is necessary at the tricuspid position, as mechanical prostheses are more prone to thrombosis at this location. Combined severe stenosis and regurgitation, as occurs with carcinoid disease, usually necessitates a surgical approach.

III. TRICUSPID REGURGITATION

A. Etiology and pathophysiology.

Any disease process that causes derangement of the TV apparatus (annulus, leaflets, chordae, and papillary muscles) can lead to TR. The most common cause of TR is not intrinsic valvular disease but rather dilation of the right ventricle, causing secondary (functional) TR. Table 17.2 lists the causes of TR.

1. The most commonly encountered type is the functional or secondary TR. Functional TR refers to the TR secondary to the left or the right heart pathology in the face of normal TV leaflet morphology. Functional TR is a dynamic entity that is regulated by several factors, including annular dilation, annular shape, pulmonary hypertension, ventricular dysfunction, and leaflet tethering.

2. TR with an anatomically abnormal valve (i.e., primary TR) may be a manifestation of congenital heart disease (e.g., Ebstein’s anomaly, atrioventricular canal defects, and ventricular septal defect [VSD]). In addition, a variety of conditions such as RHD, myxomatous degeneration, carcinoid heart disease, radiation, endomyocardial fibrosis, and the hypereosinophilic syndrome may cause scarring/thickening of the TV apparatus, resulting in poor leaflet coaptation and TR.

B. Clinical presentation

1. Signs and symptoms. The spectrum of symptoms of TR is wide and depends on its etiology and chronicity. Isolated TR is usually well tolerated. When TR and pulmonary hypertension coexist, cardiac output declines and patients

may manifest symptoms of right heart failure. Patients may present with painful hepatic congestion and substantial peripheral edema. Fatigue from reduced cardiac output is another common presentation. Patients may notice pulsations in their neck due to the prominent cv wave in the jugular venous pulse. TR often coexists with MV disease; in these patients, the symptoms associated with MV disease usually predominate.

may manifest symptoms of right heart failure. Patients may present with painful hepatic congestion and substantial peripheral edema. Fatigue from reduced cardiac output is another common presentation. Patients may notice pulsations in their neck due to the prominent cv wave in the jugular venous pulse. TR often coexists with MV disease; in these patients, the symptoms associated with MV disease usually predominate.

TABLE 17.2 Causes of Tricuspid Regurgitation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||