Tricuspid and Pulmonary Valves

The tricuspid valve is well imaged by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The septal and anterior leaflets are seen in the transverse plane (four-chamber and right ventricular inflow views), and the anterior and posterior leaflets are imaged in the longitudinal plane. Tricuspid stenosis is unusual in the absence of mitral stenosis. Even small pressure gradients across a tricuspid valve may indicate significant stenosis.

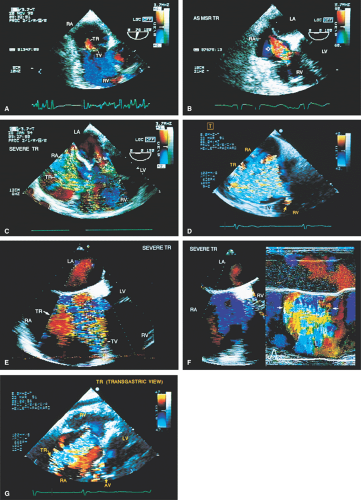

Tricuspid regurgitation is far more common than stenosis. The most common cause of moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation is right heart dilatation. Mild tricuspid regurgitation is seen commonly in healthy individuals. The absolute jet area is used to semiquantitate the severity of tricuspid regurgitation; therefore, it is important to image the tricuspid valve in multiple planes to find the maximum jet area. No angiographically validated gold standard exists for quantifying tricuspid regurgitation. In the absence of such a standard, the criteria used to quantify mitral regurgitation are frequently used. Since the right atrium is not always completely visualized on TEE in the same view as the maximum regurgitant jet area, absolute areas have been used. Mild tricuspid regurgitation is considered to be present when the maximum jet area is 4 cm2, moderate when the jet area is 4 to 8 cm2, and severe when the jet is 8 cm2. Proximal flow acceleration and a large vena contracta area are also important markers of significant regurgitation. Additionally, the right atrium generally enlarges in the setting of significant chronic tricuspid regurgitation and this is also a useful, if qualitative, sign of significant tricuspid regurgitation.

The pulmonary artery pressure can be estimated in the absence of pulmonic stenosis. As is done with transthoracic echocardiography, the systolic pressure in the right ventricle (and therefore, approximately in the pulmonary artery), is estimated as

PAsys = 4 Vmax2 + RAP

where PAsys is the pulmonary artery systolic pressure, Vmax is the maximum velocity of the regurgitant tricuspid jet, and RAP is an estimate of the right atrial pressure. Care must be taken to align the beam with the maximum tricuspid regurgitation jet, which may be more difficult on TEE than on transthoracic echocardiography with the views available. If the jet is not aligned, the pressure will be underestimated. Estimation of the pulmonary artery systolic pressure is helpful in the assessment of the reason for tricuspid regurgitation.

Tricuspid prolapse most often accompanies mitral prolapse, but can also occur in its absence. The most specific pattern of prolapse occurs when one or more of the redundant leaflets show a distinct bulge into the right atrium during systole. Prolapse may result in the entire spectrum of regurgitation, from mild to severe, and the regurgitant jet may be eccentric. In some patients, myxomatous degeneration may result in the prominent thickening of a prolapsing tricuspid valve.

Pulmonary stenotic lesions are primarily associated with congenital heart disease. However, mild pulmonary regurgitation is often noted in healthy individuals, and therefore may be considered “normal” or “physiologic.” More severe degrees of pulmonary regurgitation result from pulmonary hypertension or right heart/pulmonary artery dilatation from other causes. In the absence of an angiographic “gold standard,” the criteria used for the assessment of the severity of aortic regurgitation have also been applied for grading the severity of pulmonary regurgitation. A ratio of the jet width at its origin from the pulmonary valve to the right ventricular outflow tract diameter, taken at the same point, of 38% or less is considered mild or moderate pulmonary regurgitation, 39% to 74% is moderately severe, and 75% or more indicates severe regurgitation. The distance the pulmonary regurgitation jet travels in the right ventricular outflow tract has also been found useful in assessing its severity, especially in the presence of infundibular stenosis, which narrows the outflow tract. In our experience, a regurgitation jet reaching within 1 cm of the tricuspid valve always denotes severe pulmonary

regurgitation. It is particularly important not to rely on the presence of turbulent flow to identify tricuspid or pulmonary regurgitation since the regurgitant flow signals may be laminar and totally devoid of aliasing and variance when the right atrial or pulmonary artery diastolic pressures are high. In some such instances, torrential pulmonary and tricuspid regurgitation have been completely missed. The pulmonary valve may show redundancy, thickening, and prolapse resulting from myxomatous degeneration, and the resulting regurgitation may be eccentric. Pulmonary valve prolapse is often associated with prolapse of other valves. Both tricuspid and pulmonary valves may show evidence of infection, especially in drug addicts.

regurgitation. It is particularly important not to rely on the presence of turbulent flow to identify tricuspid or pulmonary regurgitation since the regurgitant flow signals may be laminar and totally devoid of aliasing and variance when the right atrial or pulmonary artery diastolic pressures are high. In some such instances, torrential pulmonary and tricuspid regurgitation have been completely missed. The pulmonary valve may show redundancy, thickening, and prolapse resulting from myxomatous degeneration, and the resulting regurgitation may be eccentric. Pulmonary valve prolapse is often associated with prolapse of other valves. Both tricuspid and pulmonary valves may show evidence of infection, especially in drug addicts.

FIGURE 4.1. Tricuspid regurgitation. A. A small jet of mild tricuspid regurgitation (TR). This is often seen in normal individuals. B. The regurgitant jet (arrow) is larger and represents moderate TR. Note the presence of flow acceleration on the ventricular aspect of the tricuspid valve (TV). C–G.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|