Treatments

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

♦ treatments for cardiovascular disorders

♦ patient preparation for specific types of cardiovascular treatments

♦ monitoring and home care techniques for the patient after discharge.

A look at treatments for cardiovascular disorders

Many treatments are available for patients with cardiovascular disorders; the dramatic ones, such as heart transplantation and artificial heart insertion, have received a lot of publicity. However, some more commonly used treatment measures include drug therapy, surgery, balloon catheter treatments, defibrillation, synchronized cardioversion, and pacemaker insertion.

Drug therapy

Several types of drugs are critical to the treatment of cardiovascular disorders. These drugs include:

• adrenergics

• antianginals

• antiarrhythmics

• anticoagulants

• antihypertensives

• antilipemics

• diuretics

• thrombolytics.

|

Surgery

Despite successful advances, such as single- and multiple-organ transplants, improved immunosuppressants, and improved ventricular assist devices (VADs), far more patients undergo conventional surgeries. Surgeries for the treatment of disorders of the cardiovascular system include coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB), off-pump CABG, heart transplantation, vascular repair, valve surgery, and VAD insertion.

Coronary artery bypass graft

A CABG circumvents an occluded coronary artery with an autogenous graft (usually a segment of the saphenous vein or internal mammary artery), and an internal thoracic or radial artery is also used to restore blood flow to the myocardium. CABG techniques vary according to the patient’s condition and the number of arteries needing bypass.

Construction ahead

The most common procedure, aortocoronary bypass, involves suturing one end of the autogenous graft to the ascending aorta and the other end to a coronary artery distal to the occlusion. (See Bypassing coronary occlusions.)

CABG candidates

More than 200,000 Americans (most of them male) undergo CABG each year, making it one of the most common cardiac surgeries. Prime candidates include patients with severe angina from atherosclerosis and others with coronary artery disease that have a high risk of myocardial infarction (MI). Successful CABG can relieve anginal pain, improve cardiac function and, possibly, enhance the patient’s quality of life and resumption to normal life.

CABG caveat

Although the surgery relieves pain in about 90% of patients, its long-term effectiveness is unclear. (See Relieving anginal pain with EECP, page 98.) In addition, such problems as graft closure and development of atherosclerosis in other coronary arteries may make repeat surgery necessary. In addition, because CABG doesn’t resolve the underlying disease associated with arterial blockage, CABG may not reduce the risk of MI recurrence.

|

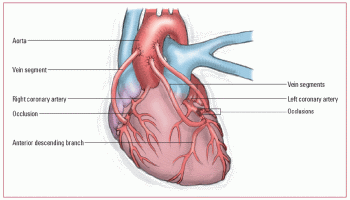

Bypassing coronary occlusions

After the patient receives general anesthesia and is placed on mechanical ventilation, autocoronary bypass surgery begins with graft harvesting. The surgeon makes a series of incisions in the patient’s thigh or calf and removes a saphenous vein segment for grafting. Most surgeons prefer to use a segment of the internal mammary artery.

Exposing the heart

Once the autografts are obtained, the surgeon performs a medial sternotomy to expose the heart and then initiates cardiopulmonary bypass. Sometimes small multiple incisions are made when a sternotomy is not the traditional approach.

To reduce myocardial oxygen demands during surgery and to protect the heart, the surgeon induces cardiac hypothermia and standstill by injecting a cold, cardioplegic solution (potassium-enriched saline solution) into the aortic root.

|

One fine sewing lesson

After the patient is prepared, the surgeon sutures one end of the venous graft to the ascending aorta and the other end to a patent coronary artery that’s distal to the occlusion. The graft is sutured in a reversed position to promote proper blood flow. The surgeon repeats this procedure for each occlusion to be bypassed.

In the example depicted below, saphenous vein segments bypass occlusions in three sections of the coronary artery.

Finishing up

When the grafts are in place, the surgeon flushes the cardioplegic solution from the heart and discontinues cardiopulmonary bypass. The surgeon then implants epicardial pacing electrodes, inserts a chest tube, closes the incision, and applies a sterile dressing.

Relieving anginal pain with EECP

Enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) can be used to provide pain relief to people with recurrent stable angina when standard treatments fail. It can reduce coronary ischemia, improve exercise tolerance, and stimulate the development of collateral circulation.

Candidates for EECP

A patient may be considered for EECP if he:

• isn’t a candidate for revascularization or if the risk of these procedures is too high

• has recurrent angina even with drug therapy and revascularization

• declines invasive procedures.

Patients with diabetes may benefit from EECP because of their increased risk of cardiovascular disease and unfavorable outcomes to revascularization procedures.

Understanding EECP

In EECP, pneumatic cuffs are wrapped around the patient’s calves, thighs, and lower buttocks. During diastole, the cuffs are sequentially inflated, starting with the calves and moving up the legs. The compression of arteries in the legs promotes retrograde arterial blood flow and coronary perfusion, similar to intra-aortic counterpulsation. At the end of diastole, cuff pressure is instantly released, reducing vascular resistance and decreasing the heart’s workload. EECP may also stimulate collateral circulation around stenosed or occluded coronary arteries.

In contrast to intra-aortic counterpulsation, EECP enhances venous return, increasing the filling pressures of the heart and, consequently, cardiac output.

Adverse effects of EECP

Although rare, the patient may experience leg discomfort, bruising, blisters, or skin abrasions from frequent cuff inflation. Because EECP increases venous return, patients with decreased left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure should be monitored closely for pulmonary congestion or edema during and after the procedure.

Other uses of EECP

Therapeutic uses of EECP may be expanded to the treatment of other cardiovascular diseases. Studies are currently looking at using EECP to treat moderate and severe left ventricular dysfunction and cardiomyopathy. Research is also being conducted on the use of EECP as an interim treatment in acute coronary syndromes and acute myocardial infarction until revascularization can be performed.

Patient preparation

• Reinforce the doctor’s explanation of the surgery.

• Explain the complex equipment and procedures used in the intensive care unit (ICU) or postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

• Explain that the patient awakens from surgery with an endotracheal (ET) tube in place and is connected to a mechanical ventilator. The patient will also be connected to a cardiac monitor and have in place a nasogastric (NG) tube, a chest tube, an indwelling urinary catheter, arterial lines, epicardial pacing wires and,

possibly, a pulmonary artery (PA) catheter. Tell the patient that discomfort is minimal and that the equipment is removed as soon as possible.

possibly, a pulmonary artery (PA) catheter. Tell the patient that discomfort is minimal and that the equipment is removed as soon as possible.

• Review incentive spirometry techniques and range-of-motion (ROM) exercises with the patient. Also teach the patient to splint the incision. When possible, this patient teaching should occur prior to surgery.

• Make sure that the patient or a responsible family member has signed a consent form.

• Before surgery, prepare the patient’s skin as ordered.

• Immediately before surgery, begin cardiac monitoring and then assist with PA catheterization and insertion of arterial lines. Some facilities insert PA catheters and arterial lines in the operating room before surgery.

Monitoring and aftercare

• After a CABG, look for signs of hemodynamic compromise, such as severe hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and shock.

• Begin warming procedures according to your facility’s policy.

• Check and record vital signs and hemodynamic parameters every 5 to 15 minutes until the patient’s condition stabilizes. Administer medications as ordered and titrate according to the patient’s response.

• Monitor electrocardiograms (ECGs) continuously for disturbances in heart rate and rhythm. If you detect serious abnormalities, notify the doctor and be prepared to assist with epicardial pacing or, if necessary, cardioversion or defibrillation.

|

Reading the map

• To ensure adequate myocardial perfusion, keep arterial pressure within the limits set by the doctor. Usually, mean arterial pressure (MAP) less than 70 mm Hg results in inadequate tissue perfusion; pressure greater than 110 mm Hg can cause hemorrhage and graft rupture. Monitor pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), central venous pressure (CVP), left atrial pressure, and cardiac output as ordered.

• Frequently evaluate the patient’s peripheral pulses, capillary refill time, skin temperature and color and auscultate for heart sounds; report any abnormalities.

• Evaluate tissue oxygenation by assessing breath sounds, chest excursion, and symmetry of chest expansion. Check arterial blood gas (ABG) results every 2 to 4 hours, and adjust ventilator settings to keep ABG values within ordered limits.

• Maintain chest tube drainage at the ordered negative pressure (usually -10 to -40 cm H2O), and assess regularly for hemorrhage, excessive drainage (greater than 200 ml/hour), and sudden decrease or cessation of drainage.

In and out

• Monitor the patient’s intake and output, and assess for electrolyte imbalance, especially hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. Assess urine output at least hourly during the immediate postoperative period and then less frequently as the patient’s condition stabilizes.

• As the patient’s incisional pain increases, give an analgesic or other drugs, as ordered.

• Throughout the recovery period and postoperative course, assess for signs and symptoms of stroke, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and impaired renal perfusion.

• After weaning the patient from the ventilator and removing the ET tube, provide chest physiotherapy. Start with incentive spirometry, and encourage the patient to splint the incision, cough, turn frequently, and deep-breathe. Assist with ROM exercises, as ordered, to enhance peripheral circulation and prevent thrombus formation.

Postperi problems

• Explain that postpericardiotomy syndrome commonly develops after open-heart surgery. Instruct the patient about signs and symptoms, such as fever, muscle and joint pain, weakness, and chest discomfort. Keep in mind that a mild transient temperature elevation may be a normal physiological response after surgery; however, temperature should be monitored closely and reported promptly if the patient does not respond to temperature-reducing medications.

• Prepare the patient for the possibility of postoperative depression, which may not develop until weeks after discharge. Reassure him that this depression is normal and should pass quickly.

• Maintain nothing-by-mouth status until bowel sounds return. Then begin the patient on clear liquids and advance his diet as tolerated and as ordered. Tell the patient to expect sodium and cholesterol restrictions and explain that this diet can help reduce the risk of recurrent arterial occlusion.

• Monitor for postoperative complications, such as stroke, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and impaired renal perfusion.

• Gradually allow the patient to increase activities as ordered. (See Using cardiac rehab.)

• Monitor the incision site for signs of infection or drainage.

• Provide support to the patient and his family to help them cope with recovery and lifestyle changes. (See Teaching the patient after CABG.)

• Monitor ECG tracings, assessing for arrthymias such as torsades de pointes due to hypomagnesemia and premature ventricular contractions due to hypokalemia.

|

Using cardiac rehab

Cardiac rehab is an exercise program to monitor and improve cardiovascular status and help the patient learn how to manage heart disease.

Elements of cardiac rehab include:

• individualized exercise program

• diet, nutrition, and weight control

• stress management

• reduction of risk factors

• lipid and cholesterol control.

Sessions are held weekly, based on patient need and tolerance. Heart rate, blood pressure, and symptoms are continuously monitored during the session. Education is provided based on the patient’s individual needs.

Minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass

Until recently, cardiac surgery required stopping the heart and using cardiopulmonary bypass to oxygenate and circulate blood. Now, MIDCAB can be performed on a pumping heart through a small thoracotomy incision. The patient may receive only right

lung ventilation along with drugs, such as beta-adrenergic blockers, to slow the heart rate and reduce heart movement during surgery.

lung ventilation along with drugs, such as beta-adrenergic blockers, to slow the heart rate and reduce heart movement during surgery.

No place like home

No place like homeTeaching the patient after CABG

Before discharge from the hospital, instruct the patient to:

• watch for and immediately notify the doctor of any signs of infection (redness, swelling, or drainage from the leg or chest incisions; fever; or sore throat) or possible arterial reocclusion (angina, dizziness, dyspnea, rapid or irregular pulse, or prolonged recovery time from exercise)

• call the doctor in the case of weight gain greater than 3 lb (1.4 kg) in 1 week; the patient may be developing congestive heart failure

• follow his prescribed diet, especially sodium and cholesterol restrictions

• maintain a balance between activity and rest by trying to sleep at least 8 hours each night, scheduling a short rest period each afternoon, and resting frequently when engaging in tiring physical activity

• participate in an exercise program or cardiac rehabilitation, if prescribed

• follow lifestyle modifications (no smoking, improved diet, and regular exercise) to reduce atherosclerotic progression

• contact a local chapter of the Mended Hearts Club and the American Heart Association for information and support

• make sure the patient understands the dose, frequency of administration, and possible adverse effects of prescribed medications

• instruct the patient to follow up with cardiology, the surgeon, and the primary care physician (PCP).

|

It’s a good thing

Advantages of MIDCAB include shorter hospital stays, use of shorter acting anesthetic agents, fewer postoperative complications (such as infection), earlier extubation, reduced cost, smaller incisions, and earlier return to work. Patients eligible for MIDCAB include those with proximal left anterior descending lesions and some lesions of the right coronary and circumflex arteries.

Patient preparation

• Review the procedure with the patient and answer his questions. Tell the patient that he’ll be extubated in the operating room or within 2 to 4 hours after surgery.

• Teach the patient to splint his incision, cough and breathe deeply, and use an incentive spirometer.

• Explain the use of pain medications after surgery as well as nonpharmacologic methods to control pain.

• Let the patient know that he should be able to walk with assistance the first postoperative day and be discharged within 48 hours.

Monitoring and aftercare

• After a MIDCAB, look for signs of hemodynamic compromise, such as severe hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and shock.

• Check and record vital signs and hemodynamic parameters every 5 to 15 minutes until the patient’s condition stabilizes. Administer medications as ordered and titrate according to the patient’s response.

• Monitor ECGs continuously for disturbances in heart rate and rhythm. If you detect serious abnormalities, notify the doctor and be prepared to assist with epicardial pacing or, if necessary, cardioversion or defibrillation since the most common arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation.

• To ensure adequate myocardial perfusion, keep arterial pressure within the limits set by the doctor. Usually, a MAP less than 70 mm Hg results in inadequate tissue perfusion; pressure greater than 110 mm Hg can cause hemorrhage and graft rupture. Monitor PAP, CVP, left atrial pressure, and cardiac output if a PA catheter was inserted.

|

• Frequently evaluate the patient’s peripheral pulses, capillary refill time, skin temperature and color and auscultate for heart sounds; report any abnormalities.

• Evaluate tissue oxygenation by assessing breath sounds, chest excursion, and symmetry of chest expansion.

• Monitor the patient’s intake and output, and assess for electrolyte imbalance, especially hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. Assess urine output at least hourly during the immediate postoperative period and then less frequently as the patient’s condition stabilizes.

• Provide analgesia or encourage the use of patient-controlled analgesia, if appropriate.

• Throughout the recovery period, assess for symptoms of stroke, pulmonary embolism, and impaired renal perfusion.

• Provide chest physiotherapy and incentive spirometry, and encourage the patient to splint his incision, cough, turn frequently, and deep-breathe. Assist with ROM exercises, as ordered, to enhance peripheral circulation and prevent thrombus formation.

• Explain that postpericardiotomy syndrome commonly develops after open-heart surgery. Instruct the patient about signs and symptoms, such as fever, muscle and joint pain, weakness, and chest discomfort.

• Prepare the patient for the possibility of postoperative depression, which may not develop until weeks after discharge. Reassure him that this depression is normal and should pass quickly.

• Maintain nothing-by-mouth status until bowel sounds return. Then begin the patient on clear liquids and advance his diet as tolerated and as ordered. Tell the patient to expect sodium and cholesterol restrictions and explain that this diet can help reduce the risk of recurrent arterial occlusion.

• Gradually allow the patient to increase activities as ordered.

• Monitor the incision site for signs of infection or drainage.

• Provide support to the patient and his family to help them cope with recovery and lifestyle changes. (See Teaching the patient after MIDCAB, page 104.)

|

Heart transplantation

Heart transplantation involves the replacement of a person’s heart with a donor heart. It’s the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage cardiac disease that have a poor prognosis, estimated survival of 6 to 12 months, and poor quality of life. A heart transplant candidate typically has uncontrolled symptoms and no other surgical options.

No place like home

No place like homeTeaching the patient after MIDCAB

Before discharge from the facility following minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB), instruct the patient to:

• continue with the progressive exercise started in the facility

• perform coughing and deep-breathing exercises (while splinting the incision with a pillow to reduce pain) and use the incentive spirometer to reduce pulmonary complications

• avoid lifting objects that weigh more than 10 lb (4.5 kg) for the next 4 to 6 weeks

• wait 2 to 4 weeks before resuming sexual activity

• check the incision site daily and immediately notify the doctor of signs of infection (redness, foul-smelling drainage, or swelling) or possible graft occlusion (slow, rapid, or irregular pulse; angina; dizziness; or dyspnea)

• perform necessary incisional care

• follow lifestyle modifications

• take medications as prescribed and report adverse effects to the doctor

• consider participation in a cardiac rehabilitation program.

No guarantee

Transplantation doesn’t guarantee a cure. Serious postoperative complications include infection and tissue rejection. Most patients experience one or both of these complications postoperatively.

Rejection and infection

Rejection typically occurs in the first 6 weeks after surgery, but it may still occur after this time (up to 1 year following transplantation). The patient is treated with monoclonal antibodies and potent immunosuppressants. The resulting immunosuppression places the patient at risk for life-threatening infection.

Patient preparation

• Reinforce the doctor’s explanation of the surgery.

• Explain the complex equipment and procedures used in the ICU and PACU.

• Explain that the patient awakens from surgery with an ET tube in place and connected to a mechanical ventilator. He’ll also be connected to a cardiac monitor and have in place a nasogastric (NG) tube, a chest tube, an indwelling urinary catheter, arterial lines, epicardial pacing wires and, possibly, a PA catheter. Tell him that discomfort is minimal and that the equipment is removed as soon as possible.

|

• Review incentive spirometry techniques and ROM exercises with the patient.

• Make sure that the patient or a responsible family member has signed an informed consent form.

• Before surgery, prepare the patient’s skin as ordered.

• Immediately before surgery, begin cardiac monitoring and then assist with PA catheterization and insertion of arterial lines. Some facilities insert PA catheters and arterial lines in the operating room before surgery.

Monitoring and aftercare

• Provide emotional support to the patient and his family. Begin to address their fears by discussing the procedure, possible complications, and the impact of transplantation and a prolonged recovery period on the patient’s life.

• After surgery, maintain reverse isolation.

• Administer immunosuppressants, and monitor the patient closely for signs of infection. Transplant recipients may exhibit only subtle signs because immunosuppressants mask obvious signs.

• Monitor vital signs every 15 minutes until stabilized, and assess the patient for signs of hemodynamic compromise, such as hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and shock.

• If necessary, administer nitroprusside (Nipride) during the first 24 to 48 hours to control blood pressure. An infusion of dopamine can improve contractility and renal perfusion.

• Volume replacement with normal saline, plasma expanders, or blood products may be necessary to maintain CVP. Monitor the patient for signs and symptoms of fluid overload, such as edema, jugular vein distention, and increased PAPs.

• Patients with an elevated PAP may receive prostaglandin E to produce pulmonary vasodilation and reduced right ventricular afterload.

• Monitor ECGs for rhythm disturbances.

• Maintain the chest tube drainage system at the prescribed negative pressure. Regularly assess for hemorrhage or sudden cessation of drainage.

When the body says no

• Continually assess the patient for signs of tissue rejection (decreased electrical activity on the ECG, right-axis shift, atrial arrhythmias, conduction defects, weight gain, lethargy, ventricular failure, jugular vein distention, and increased T-cell count).

• Keep in mind that the effects of denervated heart muscle or denervation (in which the vagus nerve is cut during heart transplant surgery) makes drugs such as edrophonium (Tensilon) and anticholinergics (such as atropine) ineffective. (See Teaching the patient after heart transplantation, page 106.)

|

No place like home

No place like homeTeaching the patient after heart transplantation

Before discharge from the facility, instruct the patient to:

• continue with the progressive exercise started in the facility

• perform coughing and deep-breathing exercises (while splinting the incision with a pillow to reduce pain) and use the incentive spirometer to reduce pulmonary complications

• avoid lifting objects that weigh more than 10 lb (4.5 kg) for the next 4 to 6 weeks

• wait 2 to 4 weeks before resuming sexual activity

• check the incision site daily and immediately notify the doctor of any signs of infection (such as redness, foul-smelling drainage, swelling, fever, or excessive pain)

• perform necessary incisional care

• follow lifestyle modifications

• take medications (which will be lifelong), as prescribed, and report adverse effects to the doctor

• consider participation in a cardiac rehabilitation program, as advised

• immediately report any episodes of chest pain or shortness of breath

• avoid crowds and anyone with an infectious illness

• comply with follow-up visits as instructed

• get the influenza vaccine

• get the pneumonia vaccine

• perform regular handwashing.

Vascular repair

Vascular repair includes aneurysm resection, aneurysm exclusion, grafting, embolectomy, vena caval filtering, endarterectomy, vein stripping, and vein ablation. The specific surgery used depends on the type, location, and extent of vascular occlusion or damage. (See Types of vascular repair.)

Life and limb

Vascular repair can be used to treat:

• vessels damaged by arteriosclerotic or thromboembolic disorders (such as aortic aneurysm or arterial occlusive disease), trauma, infections, or congenital defects

• vascular obstructions that severely compromise blood flow

• vascular disease that doesn’t respond to drug therapy or nonsurgical treatments such as balloon catheterization

• life-threatening dissecting or ruptured aortic aneurysms

• limb-threatening acute arterial occlusion.

Types of vascular repair

Several procedures exist to repair damaged or diseased vessels. These options include aortic aneurysm repair, vena caval filter insertion, embolectomy, and bypass grafting.

Aortic aneurysm repair

Aortic aneurysm repair involves removing or excluding an aneurysmal segment of the aorta. The surgeon first makes an incision to expose the aneurysm site. If necessary, the patient is placed on a cardiopulmonary bypass machine. Next, the surgeon clamps the aorta, resects the aneurysm, and repairs the damaged portion of the aorta. A synthetic bypass graft may be used.

|

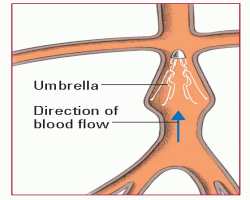

Vena caval filter insertion

A vena caval filter traps emboli in the vena cava, preventing them from reaching the pulmonary vessels. Inserted percutaneously by catheter, the vena caval filter, or umbrella, traps emboli but allows venous blood flow.

|

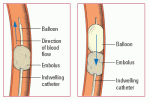

Embolectomy

To remove an embolism from an artery, a surgeon may perform an embolectomy. In this procedure, he inserts a balloon-tipped indwelling catheter in the artery and passes it through the thrombus (as shown below left). He then inflates the balloon and withdraws the catheter to remove the thrombus (as shown below right).

|

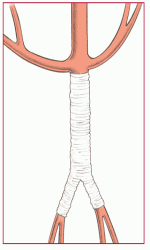

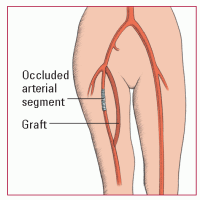

Bypass grafting

Bypass grafting serves to bypass an arterial obstruction resulting from arteriosclerosis. After exposing the affected artery, the surgeon anastomoses a synthetic or autogenous graft to divert blood flow around the occluded arterial segment. The autogenous graft may be a vein or artery harvested from elsewhere in the patient’s body. This illustration shows a femoropopliteal bypass.

|

Repair despairs

All vascular surgeries have the potential for vessel trauma, emboli, hemorrhage, infection, and other complications. Grafting carries added risks because the graft may occlude, narrow, dilate, or rupture.

Patient preparation

• Make sure the patient and his family understand the doctor’s explanation of the surgery and its possible complications.

• Ensure a patient consent is signed.

• Tell the patient that he’ll receive a general anesthetic and will awaken from the anesthetic in the ICU or PACU. Explain that he’ll have an intravenous (IV) line in place, ECG electrodes for continuous cardiac monitoring and, possibly, an arterial line or a PA catheter to provide continuous pressure monitoring. He may also have a urinary catheter in place to allow accurate output measurement. If appropriate, explain that he’ll be intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation.

Flow check

• Before surgery, perform a complete vascular assessment. Take vital signs to provide a baseline. Evaluate the strength and sound of the blood flow and the symmetry of the pulses, and note bruits. Record the temperature of the extremities, their sensitivity to motor and sensory stimuli, and pallor, cyanosis, or redness. Rate peripheral pulse volume and strength on a scale of 0 (pulse absent) to 4 (bounding pulse), and check capillary refill time by blanching the fingernail or toenail; normal refill time is less than 3 seconds.

• As ordered, instruct the patient to restrict food and fluids for at least 12 hours before surgery.

Keep your guard

• If the patient is awaiting surgery for aortic aneurysm repair, be on guard for signs and symptoms of acute dissection or rupture. Especially note sudden, severe, tearing pain in the chest, abdomen, or lower back; severe weakness; diaphoresis; tachycardia; or a precipitous drop in blood pressure. If any of these signs or symptoms occurs, notify the doctor immediately.

Monitoring and aftercare

• Check and record the patient’s vital signs every 15 minutes until his condition stabilizes, then every 30 minutes for 1 hour, and hourly thereafter for 2 to 4 hours. Report hypotension and hypertension immediately.

• Auscultate heart, breath, and bowel sounds, and report abnormal findings. Monitor the ECG for abnormalities in heart rate or rhythm. Also monitor other pressure readings, and carefully record intake and output.

• Check the patient’s dressing regularly for excessive bleeding.

• Assess the patient’s neurologic and renal function, and report abnormalities.

• Provide analgesics, as ordered, for incisional pain.

• Frequently assess peripheral pulses, using a handheld Doppler if palpation is difficult. Mark on the skin the location of the Doppler signals. Check all extremities bilaterally for muscle strength and movement, color, temperature, and capillary refill time.

• Change dressings and provide incision care, as ordered. Position the patient to avoid pressure on grafts and to reduce edema. Administer antithrombotics, as ordered, and monitor appropriate laboratory values to evaluate effectiveness.

• Assess for complications, and immediately report relevant signs and symptoms. (See Table 5.1, Vascular repair complications, page 110.)

• As the patient’s condition improves, take steps to wean him from the ventilator, if appropriate. To promote good pulmonary hygiene, encourage the patient to cough, turn, and deep-breathe frequently.

• Assist the patient with ROM exercises, as ordered, to prevent thrombus formation. Assist with early ambulation to prevent complications of immobility.

• Provide support to the patient and his family to help them cope with recovery and lifestyle changes. (See Teaching the patient after vascular repair, page 111.)

|

Valve surgery

Types of valve surgery include valvuloplasty (valvular repair), commissurotomy (separation of the adherent, thickened leaflets of the mitral valve), and valve replacement (with a mechanical or prosthetic valve).

Attention to prevention

Valve surgery is typically used to prevent heart failure in a patient with valvular stenosis or insufficiency accompanied by severe, unmanageable symptoms.

Pressure points

Because of the high pressure generated by the left ventricle during contraction, stenosis and insufficiency most commonly affect the mitral and aortic

valves. Other indications for valve surgery depend on the patient’s symptoms and on the affected valve:

valves. Other indications for valve surgery depend on the patient’s symptoms and on the affected valve:

|

Table 5.1: Vascular repair complications | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||