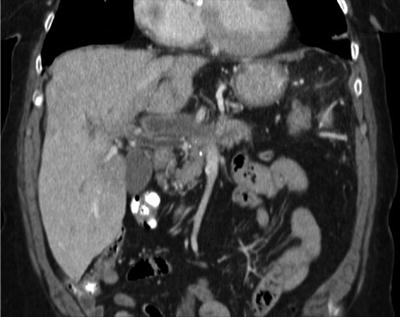

Fig. 24.1

CT showing thrombus in the superior mesenteric vein

From a strictly historic standpoint, interventions to “debulk” the thrombus, relieve the venous obstruction, and decrease venous hypertension have been described. Mergenthaler and Harris reported in 1967 a successful case of venous thrombectomy of an acutely thrombosed SMV during a planned pancreatoduodenectomy [4]. Inahara further reported on planned, open, surgical thrombectomy in 1971 and reviewed both clinical and experimental aspects of the treatment of MVT understood at the time. In his review, anticoagulation after intervention was required, and all patients with suspected diagnosis underwent an operation [5]. If bowel was compromised, the involved bowel was resected based on the clinician’s judgment with the sole intent of preserving as much viable intestine as possible. Second-look operations were often warranted; however, single resection procedures have been successful with comparable mortality when the demarcation of viable and nonviable bowel is obvious and when anticoagulation was timely. Prior to our better understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of acute MVT, mortality early on was exceedingly high, ranging from 40 to 70 % in some reports.

As our knowledge of the etiopathogenesis of MVT has matured, further evidence supported the use of immediate anticoagulation in the pre- and perioperative period to improve bowel salvage and decrease mortality. If the diagnosis of MVT has been made in a patient with acute onset abdominal pain, full anticoagulation should be started immediately (preferably preoperatively but if not, intraoperatively) to prevent further extension of thrombosis; no attempt should be made to delay full anticoagulation until after the abdomen is closed because further extension of the thrombosis can occur during the perioperative period of relative hypercoagulability (Fig. 24.2). This aggressive anticoagulation has been shown in several studies both to prevent progression and to improve survival [2, 6, 7]. Many of these reports utilize and recommend surgical exploration and resection of compromised bowel with or without a second-look operation. Mortality remained high (10–40 %) but has improved with this aggressive strategy of immediate anticoagulation.

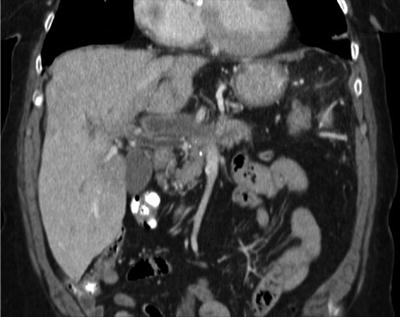

Fig. 24.2

CT showing thrombus extending up into the portal vein

Clinical experience of attempts at nonoperative management led to a retrospective assessment of clinical outcomes in two published series. These reports challenged the use of routine operative intervention in conjunction with anticoagulation. In the first study, Brunaud and colleagues evaluated their 12-year single-center experience [8]. They found that of the 26 patients treated, the overall morbidity was 35 % and mortality was 19 %. With further comparative analysis, the early group with treatment based on operative intervention (n = 14) and late treatment group of anticoagulation (n = 12) showed no difference in mortality between groups; indeed, nonoperative management was at least as good as open intervention. In review of the pathology reports of bowel resected in the operative group, these investigators found that 10 of 12 patients had only mucosal necrosis, begging the question of whether operative intervention and intestinal resection could have been avoided [8].

In a similar study, Zhang and colleagues were able to show a benefit of nonoperative management in many patients with acute MVT [9]. In their report, 41 patients were treated for acute MVT over a 25-year period. Again, a change in management occurred based on the observation that a nonoperative approach of anticoagulation and close observation could be successful. They found a 39 % mortality in the group undergoing early operation (13 patients) versus the results in the 28 patients treated initially by a nonoperative approach with anticoagulation first; 32 % of these patients treated with close observation eventually underwent operation because of progression of symptoms [9]. Clearly, in the absence of peritonitis or clinical instability, a trial of nonoperative management with anticoagulation is warranted in most patients without peritonitis.

Systemic anticoagulation with the addition of targeted thrombolytic strategies has also been tried, albeit with various success and complications. Systemic thrombolytic therapy has been shown to be of little benefit and is accompanied by an extensive list of contraindications, making its usefulness prohibitive. In contrast, local directed delivery of thrombolytics into the superior mesenteric artery or into the venous segment directly or from a transjugular approach has been shown to improve venous flow in selected cases [10]. Although several case reports suggest some success, concern remains about the overall usefulness and practicality of these interventional approaches in the setting of a condition often difficult to diagnose that is often delayed several days and can progress to the need for operative intervention because of compromised bowel. Opponents of thrombolytic therapy suggest that when providing lytic therapy directly into the superior mesenteric artery, there is no way to guarantee delivery to the segment of venous thrombosis, because the lytic agents may just sidestep through collaterals. In this setting, there is no benefit and only increased risk of bleeding. Contrary to the indirect route of lytic infusion, percutaneous access to the extrahepatic portal and mesenteric venous system is possible and may offer a more beneficial approach to the retrograde delivery of the lytic agents directly at the site of thrombus.

With advances in endovascular techniques, minimally invasive efforts to debulk venous thrombus or perform thrombectomy have been attempted in several reports [11–13]. Unlike peripheral venous thrombosis, percutaneous access to the superior mesenteric and portal venous system can be problematic but can usually be obtained through the liver (transhepatically or via a transjugular approach) in a fashion similar to that for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. Once access is established, directed lytic therapy or mechanical thrombectomy can be attempted. Wasselius et al. expanded this concept with an aggressive combined approach via the superior mesenteric artery, portal vein (partial), and proximal intrahepatic branches [13]. Simultaneous access of the common femoral artery and transjugular intrahepatic access to the portal venous system allowed a mechanical venous thrombectomy combined with intra-arterial and intravenous delivery of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) at a dose of 1 mg/h. This aggressive approach led to thrombolysis of a main branch of the superior mesenteric vein with venous decompression of the bowel. Their patient avoided operation, resumed eating in 3 days, and was kept on low-molecular-weight heparin with no bleeding events or other complications [13].

Obviously, with these more aggressive scenarios, the patient must be assessed repeatedly for worsening of their clinical condition or development of peritonitis. Such deterioration demands immediate exploration and resection of compromised, irreversibly ischemic bowel. In the setting of partial systemic thrombolytic treatment, an increased risk of bleeding is present. In a report from Hollingshead and colleagues of transcatheter thrombolytic therapy of acute MVT, although 75 % of patients had improvement in their clot burden and 85 % had resolution of their MVT, 60 % experienced a major complication of which bleeding was the most common [14].

The proposed duration of anticoagulation is variable across reports and depends heavily on the underlying etiology, resolution of symptoms, and the risk of continued anticoagulation. In the absence of a hereditary or acquired thrombotic disorder, anticoagulation is recommended for 6–12 months. During systemic anticoagulation, the risk of bleeding is low, but recurrence is quite high and occurs most frequently in the first 30 days after operation and in the area of bowel resection or thrombosis [15, 16]. A large, single-series report from Rhee et al. demonstrated recurrence in 36 % of patients despite aggressive anticoagulation; three-quarters of the recurrences developed during the same hospitalization or within 30 days, highlighting the need for close postoperative follow-up, even after discharge, at least for the first month or two [2]. Residual thrombus in the mesenteric venous system acts as a nidus and may propagate into larger veins. Complete resection of involved bowel and prevention of propagation by maintaining the international ratio (INR) on warfarin therapy in the range of 2.0–3.0 appears to be the best course to limit recurrence. Both unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin have been used successfully to bridge to warfarin. The newer direct thrombin inhibitors, like Pradaxa and Xarelto, have not been evaluated in the setting of MVT and, therefore, cannot be recommended at this time until studied formally for this type of thrombosis. With all of these approaches to prevent propagation of thrombus and limit thrombus burden in the mesenteric venous system, currently mortality rates have decreased to 0–23 % [3]. An algorithm for management of acute MVT is proposed in Fig. 24.3.

Fig. 24.3

Algorithm for the management of chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis. TIPS transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Subacute Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis

Patients who have had symptoms present for days to weeks and thrombus in the mesenteric venous system are categorized as having subacute MVT. Some reports have combined the patients meeting these criteria with those patients with chronic MVT [2]. Mostly likely, these patients had a mild, less acutely symptomatic MVT that extended to involve more venous drainage beds leading to exacerbation of pain and other symptoms. Because of the difficulty in diagnosis of subacute MVT, a strong history of clotting disorders both personal or within close family members should raise suspicion. Patients with subacute MVT often have had an extensive work-up with multiple studies and subspecialists involved. Ideally, once the diagnosis is made, anticoagulation should be initiated immediately to limit further extension of the thrombus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree