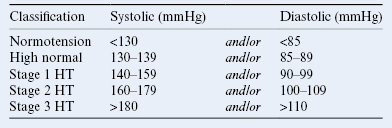

Hypertension is defined pragmatically as the level of blood pressure (BP) above which therapeutic intervention can be shown to reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (Table 38.1). Risk increases progressively with both systolic and diastolic BP levels. Epidemiological studies predict that a long-term 5–6-mmHg diminution of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) should reduce the incidence of stroke and CHD by about 40 and 25%, respectively. However, rises in systolic pressure are now given more emphasis and isolated systolic hypertension (ISH), which often develops in the elderly, is particularly deleterious.

Table 38.1 Classification of adult blood pressure by the US Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. HT, hypertension.

Individual BP measurements can vary significantly, and current guidelines state that, unless severe, hypertension (BP >140/90 mmHg) initially detected in the clinic should be confirmed using an ambulatory BP monitor which records multiple BP measurements over a 24-hour period. Tests for damage to target organs vulnerable to hypertension (e.g. eyes, kidneys) and assessment of other cardiovascular risk factors should also be carried out. Those with stage 1 hypertension should then be treated if they have overt cardiovascular disease, diabetes, target organ damage, renal disease or an overall cardiovascular risk of >20% per 10 years (as estimated using risk tables derived from the Framingham study; see Chapter 34). All those with stage 2 or 3 hypertension should be treated. The goal of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce the blood pressure to below 140/90 mmHg (or to below 130/80 mmHg in diabetics and those with renal disease).

Lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction, regular aerobic exercise and limitation of dietary sodium and alcohol intake can often normalize pressure in mild hypertensives. They are also useful adjuncts to pharmacological therapy of more severe disease, and have the important added bonus of reducing overall cardiovascular risk. However, adequate BP control usually requires the lifelong use of antihypertensive drugs. These act to reduce cardiac output and/or total peripheral resistance.

Thiazide diuretics cause an initial increased Na+ excretion by the kidneys, which is due to inhibition of Na+/Cl− symport in the distal nephron. This leads to a fall in blood volume and cardiac output. Subsequently, blood volume recovers, but total peripheral resistance falls due to an unknown mechanism. Thiazide diuretics (e.g. chlorthalidone, indapamide) can cause hypokalaemia by promoting Na+–K+ exchange in the collecting tubule. This can be prevented by giving K+ supplements, or also by combining thiazide diuretics with K+

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree