Chapter 3

Trauma and Immunosuppressive Diseases

Written by H. van Aswegen and B.M. Morrow

Nobody is exempt of the risk from being involved in a traumatic event. The result is that people who suffer from chronic health problems may end up in hospital due to traumatic injury and not due to exacerbation of their disease. A group of people at particular risk after traumatic injury are those who have immunosuppressive diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), as they may have an altered response to injury.

This chapter provides the physiotherapist with information about:

•The pathogenesis of HIV and AIDS.

•Pulmonary diseases that may develop as a result of HIV and AIDS.

•Pulmonary complications associated with antiretroviral therapy.

•Extrapulmonary complications associated with HIV and antiretroviral therapy.

3.1. Introduction

Despite the decline in new HIV infections (about 20% globally between 1999 and 2009; 25% in 33 countries including sub-Saharan Africa), as a result of both HIV prevention strategies and the natural course of the epidemic (UNAIDS, 2010), HIV remains a serious public health concern in some areas of the world. The resurgence of HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia is cause for concern, as the incidence of HIV in these countries has tripled since 2000 (UNAIDS, 2010). In regions with high HIV prevalence, knowledge of underlying obstructive and restrictive respiratory conditions and the effects of HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART) on other organ systems are essential to assist physiotherapy clinicians in understanding the clinical presentation of an HIV-infected patient who has suffered traumatic injury.

3.2. Pathogenesis of HIV and AIDS

AIDS is a syndrome of opportunistic diseases caused by HIV. HIV is a retrovirus which attacks the immune system by transporting its own genetic material, namely ribonucleic acid (RNA), into body cells via cell surface receptors and, particularly, the CD4 receptors. HIV uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase to copy itself inside the infiltrated cells and forms deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) which is earmarked as proviral DNA. The proviral DNA lies dormant until the cell is activated and then the proviral DNA forms RNA, which forms the basis for the production of new HIV under the control of enzymes such as proteases. The young HIV leaves the infiltrated cells, matures and goes off to invade more cells via their CD4 receptors (Wesselingh and French, 2003; Van Dyk, 2008). Perinatally infected children progress to symptomatic disease (AIDS) more rapidly than HIV-infected adults. Death (apoptosis) of CD4 lymphocytes and abnormalities in the T-lymphocyte helper maturation, along with other defects, lead to susceptibilities to viral and intracellular organisms. HIV-infected children are further predisposed to bacterial sepsis as a result of defects in B-lymphocytic function, natural killer cell activity, neutrophil bactericidal activity and defective antigen-specific immunoglobulin production, all despite an increase in total globulin fraction. Encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumonia are particular problems in children due to greater antibiotic resistance (Madhi et al., 2000; Musiime et al., 2013). HIV-infected children may also present with cardiac dysfunction (including dysrhythmia, left ventricular systolic function, increased left ventricular mass and pericardial effusion), anaemia and encephalopathy (Harmon et al., 2002; Okoromah et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2013).

3.3. HIV and AIDS and the Pulmonary System

People with HIV infection seem to be at increased risk of developing pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), changes in lung parenchyma that lead to restrictive disease and infective diseases (Morris et al., 2011). The antiretroviral medication that many people with HIV take on a daily basis has also been associated with changes observed in the pulmonary system (Morris et al., 2011). A short discussion of these pulmonary complications and the diseases that occur in adults and children living with HIV or AIDS follows below. Table 3.1 summarises the common pulmonary complications encountered in adults and children living with HIV or AIDS.

3.3.1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

3.3.1.1. Emphysema

People who live with HIV are at particular risk of developing COPD due to the high prevalence of smoking and intravenous drug use observed in this population (Raynaud et al., 2011). Evidence of small airways disease in the form of early emphysema observed through high resolution computed tomography (CT) scans taken in people with HIV has been reported by various researchers. Lung function abnormalities in people with HIV (prior to the onset of AIDS) such as impaired diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO), lowered forced expiratory volume in one second and lower forced expiratory flow have also been reported by several authors (King et al., 1997; Diaz et al., 1999; Gelman et al., 1999; Morris et al., 2011; Raynaud et al., 2011). HIV has also been linked to an acceleration of the onset of smoking-related emphysema, likely due to cytotoxic lymphocyte activity. Pulmonary function abnormalities continue to be present even in people with HIV who are on ART. A possible reason for this finding is that HIV-infected individuals on ART have a longer life expectancy and therefore are exposed to the detrimental effects of smoking for a longer time period (Rosen, 2008; Gingo et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2011; Raynaud et al., 2011).

•Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema, bronchiectasis) •Tuberculosis (pleural, pulmonary, upper airways) •Pneumonia (pneumocystic, bacterial) •Decreased diffusion capacity •Pulmonary fibrosis •Repeated respiratory tract infections |

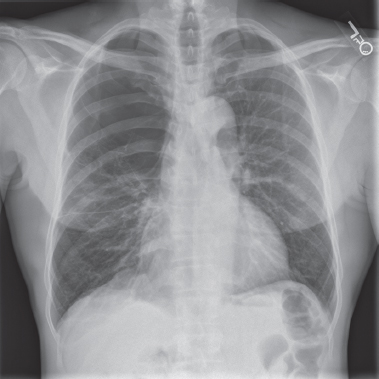

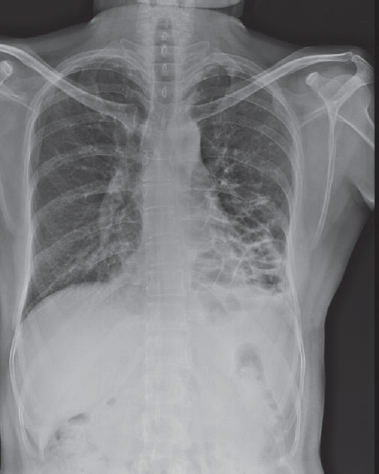

Presenting symptoms of emphysema include breathlessness on exertion, chest tightness, cough and wheeze as a result of airflow limitation due to peripheral airway remodelling, hypoxaemia and hypercapnia. As the disease progresses, chest configuration changes to that of a barrel-shaped appearance and pursed lip breathing is used in an attempt to splint open airways that collapse prematurely on expiration to allow for improved expiratory flow and less air trapping (McKenzie et al., 2003). Radiological features of emphysema are characterised by dark hyperinflated lung fields, flattened hemidiaphragms and an elongated heart shadow (Fig. 3.1). Bullae may be visible on chest x-rays and CT scans in the advanced phase of emphysema (Corne and Pointon, 2010) (Fig. 3.2).

3.3.1.2. Bronchiectasis

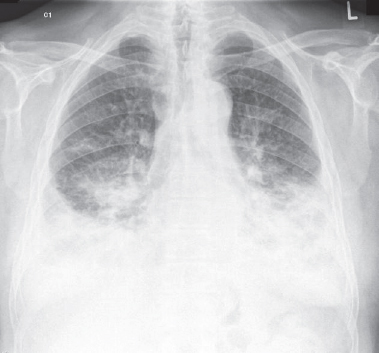

People with HIV have a high tendency to develop airway diseases such as bronchiectasis even if they do not smoke. Asymptomatic people may complain of a dry non-productive cough. Symptomatic people present with dyspnoea, wheezing and increased amounts of purulent sputum production, especially during periods of exacerbation (Tino and Weinberger, 2010). Radiological features of bronchiectasis include increased density of affected lobes with tramline shadows (diseased bronchi seen side on) towards the lung periphery. Ring shadows (diseased bronchi seen end on) may also be visible (Corne and Pointon, 2010) (Fig. 3.3).

Fig. 3.1:Chest x-ray of a patient with early signs of emphysema and right upper lobe collapse. Note the hyperinflation of the left lung with flattened hemidiaphragm and elongated heart shadow. The shape of the right hemidiaphragm appears normal due to the volume loss in the upper lobe.

Fig. 3.2:Chest x-ray of a patient with a large right upper lung bulla due to paraseptal emphysema. Published with permission from Jeffrey L. Koning MD, www.radiologypics.com.

Fig. 3.3:Chest x-ray of a male patient with bronchiectatic changes in the left basal lung segments. Published with permission from Radiopaedia.org.

3.3.1.3. Implications for physiotherapy

It is important that physiotherapists remember to include education on management of episodes of breathlessness, the correct usage of prescribed symptom-relieving pulmonary medication, especially those administered through an inhaler device and effective methods of self-management of pulmonary hygiene in their management of a patient with HIV or AIDS and COPD in the trauma intensive care unit (ICU) and ward settings. Referral to a pulmonary rehabilitation programme, if the patient is not involved with one already, after discharge from hospital is also recommended.

3.3.2. Mycobacterium infections

3.3.2.1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The highest risk factor for the development of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is HIV infection (Boyton, 2005; Rosen, 2008). Tuberculosis (TB) recurrence is higher in people with HIV who are not on ART than in those on therapy. Tuberculosis may accelerate the progression of HIV infection due to suppressed cell immunity that leads to increased HIV replication and mutation in the lung, and may therefore be associated with higher mortality in HIV infection (Boyton, 2005; Rosen, 2008).

Presenting symptoms of post-primary pulmonary TB are non-specific and include: fever and night sweats, weight loss, anorexia, malaise and general weakness. The cough that develops starts out as a dry cough and eventually becomes productive of purulent secretions, with or without streaks of blood, or even massive haemoptysis. Subpleural parenchymal lesions may lead to the development of chest pain and dyspnoea may develop in extensive disease (Raviglione and O’Brien, 2010). Post-primary TB on chest x-rays is characterised by an increased density of the affected lobes due to fibrotic changes in the lung parenchyma as a result of the reactivation of latent infection (Fig. 3.4). Small infiltrations on chest x-rays indicate limited parenchymal infection, whereas large cavity formation is indicative of massive parenchymal infection (Raviglione and O’Brien, 2010). Classic radiological features of miliary TB include a ‘ground glass appearance’ throughout both lungs. Despite this ground glass appearance the normal anatomy of the lung is still visible (Corne and Pointon, 2010).

Fig. 3.4:Chest x-ray of a patient with post-primary TB in the lower lung regions. Published with permission from Radiopaedia.org.

3.3.2.2. Mycobacterium xenopi

A less common respiratory disease, caused by Mycobacterium xenopi in people with HIV infection, has also been reported. Mycobacterium xenopi is an opportunistic pathogen which leads to the development of pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract diseases. Presenting symptoms include long-lasting low-level fever, weight loss, night sweats, diffuse lymphadenopathy, mild chest pain and cough, and it is often misdiagnosed as TB. However, mortality associated with Mycobacterium xenopi remains low (Manfredi et al., 2003).

3.3.2.3. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Extrapulmonary TB is common in HIV-infected patients. If the upper airways are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis the patient may present with chronic productive cough, hoarseness of the voice, dysphonia and dysphagia. Patients with pleural TB may present with pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea and fever if the effusion is large. Extrapulmonary TB often includes infection of the lymphatic system and the pericardium (Raviglione and O’Brien, 2010).

Mycobacterium xenopi may affect extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bone and joints, endocardium and genitourinary tract (Manfredi et al., 2003).

3.3.2.4. Implications for physiotherapy

It is often difficult to diagnose TB in HIV-infected patients in a timely manner due to increased frequency of negative sputum smears and atypical radiographic findings (Raviglione and O’Brien, 2010). Physiotherapists that treat patients who are infected with HIV in the trauma ICU setting should therefore be meticulous in adherence to infection control principles to reduce their own risk of exposure to TB.

3.3.3. Pulmonary complications associated with antiretroviral therapy

The morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection has changed dramatically worldwide due to the use of combination ART. Some clinical problems that relate to the use of ART in critically ill patients have, however, been reported (Huang et al., 2006). Intensive care unit admission for people with HIV has mostly centred on the development of respiratory failure due to Pneumocystis pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia and TB. However, respiratory failure can also result from immune reconstitution syndromes to TB, pneumocystic pneumonia and other bacterial diseases after the initiation of ART (Boyton, 2005; Huang et al., 2006). The development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients with HIV infection who are critically ill necessitates lung protective ventilation strategies according to guidelines produced by the ARDS network. Lung protective ventilation strategies are recommended in order to minimise the risk for the development of a spontaneous pneumothorax (due to decreased lung compliance) while the patient receives mechanical ventilation (Huang et al., 2006). Lung protective ventilation strategies are not only recommended for patients with HIV but also for all patients with ARDS in order to minimise the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury.

3.3.4. Restrictive pulmonary disease

Impairment in DLCO in the lungs of people living with HIV (regardless of CD4 count) has been reported in the literature. Parenchymal lung damage secondary to HIV-related inflammatory events has been proposed as a cause for this abnormality (Diaz et al., 1999). People infected with HIV seem to be at higher risk of the development of lung cancer and pulmonary fibrosis compared to their non-infected counterparts (Crothers et al., 2011). Patients with restrictive pulmonary disease present with a dry cough and progressive shortness of breath during activities of daily living as the disease progresses.

3.3.4.1. Implications for physiotherapy

Physiotherapy management of patients with HIV and impairments in DLCO in the trauma ICU and ward setting includes adequate provision of supplemental oxygen and close monitoring of changes in vital signs when patient activity levels are increased. Long-term goals of management should include education of the patient on the management of episodes of breathlessness if the patient complains of frequent episodes of dyspnoea during activities of daily living.

3.3.5. Paediatric pulmonary disease

In children, HIV infection is also associated with severe opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis pneumonia, which continues to be a significant problem in some parts of the world, with high morbidity and mortality, despite the availability of ART and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes (Morrow et al., 2010). Tuberculosis is the cause of death in 13% of people with AIDS (Ackerman and Singhi, 2010), and pulmonary TB is frequently diagnosed in HIV-infected children. Those who are started on ART are at particular risk of the development of pulmonary TB due to drug-induced immune reconstitution (Zampoli et al., 2007; Walters et al., 2008). Bacterial and viral respiratory tract infections are also more common and often more severe than in HIV-negative children (Morrow et al., 2006). Such repeated infections in HIV-positive children (not on ART) lead to irreversible airway damage, which may be a precursor for the development of COPD in later life. Children with immune compromise are also more likely to be at risk of nosocomal infections (both bacterial and viral) whilst in hospital, which in turn is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Foglia et al., 2007; Morrow and Argent, 2009). Therefore, special care with regard to infection control and prophylactic measures has to be taken in all HIV-infected or HIVexposed paediatric trauma victims.

Key Messages

Respiratory signs and symptoms that may be evident in patients who live with HIV/AIDS and pulmonary disease:

•Chest pain (pleuritis due to pneumonia, pleural effusion due to TB, pulmonary TB).

•Decreased tidal volumes (pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary TB).

•Decreased lung compliance (pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary TB).

•Dry cough (pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary TB).

•Excessive secretion production (bronchiectasis, emphysema).

•Shortness of breath (large pleural effusion, pneumonia, pulmonary TB, pulmonary fibrosis).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree