Transthoracic Hiatal Hernia Repair

Jules Lin

Mark Orringer

DEFINITION

The combined Collis-Nissen transthoracic hiatal hernia repair described in this chapter involves mobilization of the distal esophagus, herniated stomach and hernia sac, preservation of the vagus nerves, and a fundoplication through a left posterolateral thoracotomy with an esophageal lengthening procedure when necessary (to allow a 3- to 5-cm tension-free intraabdominal segment of distal “esophagus”).

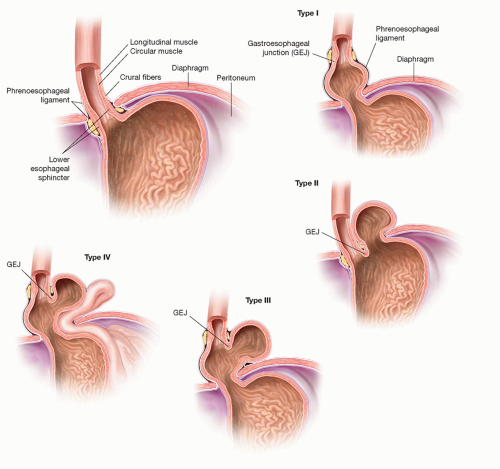

The two major categories of hiatal hernias include sliding (type I) and paraesophageal (type II, pure paraesophageal hernia with the gastroesophageal junction fixed at the hiatus; type III, combined hiatal hernia where the cardia is above the diaphragm and the fundus is herniated alongside the esophagus; and type IV, with herniation of the stomach along with the colon, small bowel, or spleen) (FIG 1).1,2,3

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A detailed history and physical must be performed focusing on heartburn and reflux symptoms, response to medical treatment as well as the characteristics and degree of dysphagia, regurgitation, pain, bloating, or anemia. In a series of 240 patients with a paraesophageal hernia, Patel et al.4 found that 68% of patients had reflux symptoms, 67% abdominal or chest pain, 33% anemia, and 33% dysphagia. The absence of severe reflux symptoms in most patients with paraesophageal hiatal hernias does not diminish the seriousness of this problem with its unpredictable potential for strangulation, perforation, bleeding, and aspiration pneumonia. More subtle symptoms may include early satiety and/or left shoulder and back pain with eating, loud borborygmi often heard across the room by the patient’s family, or acute shortness of breath with bending forward.

Any previous chest or abdominal operations or endoscopic dilations should be noted.

The history should include the patient’s current functional status and exercise tolerance.

A complete physical examination should be performed with attention to auscultation of the heart and lungs and palpation of the abdomen.

Routine laboratory studies, including a complete blood count and a basic chemistry panel, should be included as part of the preoperative evaluation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

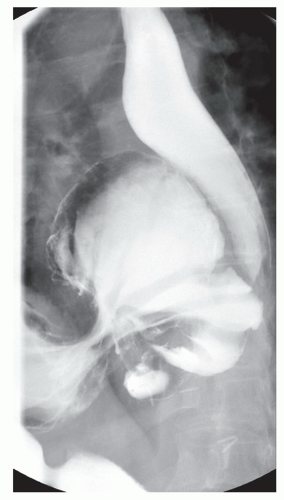

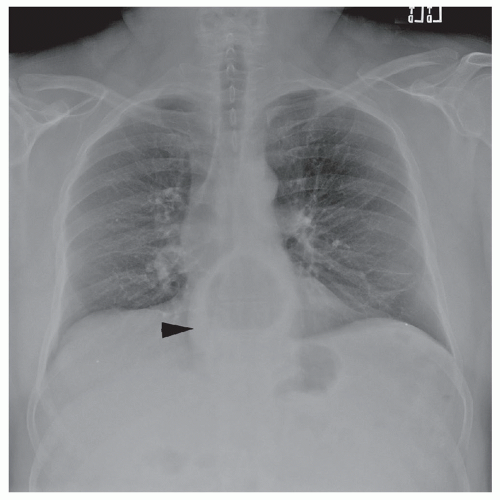

A chest x-ray (FIG 2) may show a mediastinal air fluid level, suggesting the presence of a paraesophageal hernia.

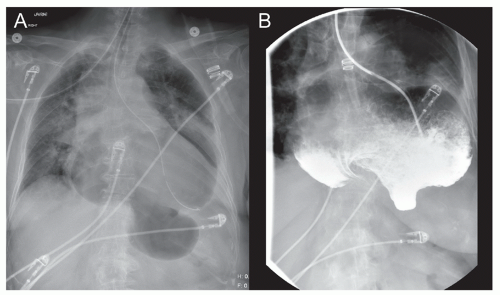

A barium swallow (FIG 3) should be performed to delineate the esophageal and gastric anatomy and may show reflux, although this is not a reliable finding. Accompanying esophageal dysmotility from the “accordioned” esophagus is common. The esophagram can also be useful when obstruction from gastric volvulus is suspected (FIG 4).

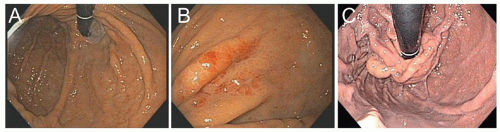

An esophagoscopy (FIG 5) should be performed to evaluate for evidence of esophagitis, Barrett’s mucosa, esophageal carcinoma, or esophageal shortening. Suspicious areas should be biopsied. The gastric mucosa should also be examined for Cameron erosions, especially when there is a history of anemia. Caution should be exercised to avoid excessive air insufflation during flexible esophagogastroscopy in the patient with a paraesophageal hiatal hernia lest the intrathoracic stomach becomes overdistended, resulting in hemodynamic instability.

For patients complaining of persistent nausea, a gastric emptying study may be obtained to evaluate for gastroparesis.

When there is no hiatal hernia or a small sliding hiatal hernia, esophageal manometry and 24-hour pH probe monitoring with impedance are performed, with antireflux medications discontinued for 72 hours, to document the presence of gastroesophageal reflux, association with the patient’s symptoms, and to evaluate for esophageal dysmotility. However, in the presence of a paraesophageal hernia, we do not routinely perform these studies. Many of these patients will have some degree of dysmotility in the presence of a chronic hiatal hernia that frequently improves after hiatal hernia repair. The presence of a symptomatic hiatal hernia is a mechanical issue, and the indication for repair is the paraesophageal hernia itself regardless of the presence of acid reflux.

Patients suspected of having an incarcerated hiatal hernia (FIG 4) with severe epigastric pain and regurgitation should undergo an esophagram and nasogastric tube decompression followed by an emergent hiatal hernia repair.

FIG 2 • Chest x-ray demonstrates an air fluid level (arrowhead) consistent with a type III hiatal hernia. |

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Sliding hiatal hernias are repaired when there has been incomplete control of reflux symptoms despite medical therapy (Table 1) and after confirmation of abnormal acid reflux on 24-hour pH probe. Other indications include complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—recurrent aspiration, the development of a reflux stricture, and recurrent bleeding from esophagitis.

Paraesophageal hernias are more likely to present with obstructive symptoms due to the chronic gastric volvulus and repair is generally recommended in the functional patient.3

There has been controversy regarding the optimal surgical approach (laparoscopic vs. transthoracic), the need for an antireflux procedure, and the assessment of esophageal shortening.1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 The pneumoperitoneum used during laparoscopic repair displaces the diaphragm upward, making intraoperative assessment of esophageal shortening more challenging. In addition, performing a lengthening procedure laparoscopically is more difficult due to the angle of the approach. Taking adequate bites of the attenuated crura is also more difficult due to the tension induced by the pneumoperitoneum, which could contribute to hernia recurrence after laparoscopic repair. A transthoracic approach with an esophageal lengthening procedure, similar to a relaxing incision for an inguinal hernia repair, may be optimal even for a small sliding hiatal hernia in morbidly obese patients due to the increased risk of recurrence. In a series of 240 patients with paraesophageal hiatal hernias, documented acid reflux decreased from 88% preoperatively to 4% after a transthoracic Collis-Nissen procedure, whereas Williamson et al.6 reported an 18% incidence of postoperative reflux after a selective approach to adding an antireflux procedure. As a

result, we advocate an antireflux procedure with all paraesophageal hiatal hernia repairs.4,6

With larger paraesophageal hernias, transthoracic Collis-Nissen repair remains the standard against which other approaches must be compared.4

FIG 5 • Esophagoscopy with retroflexed views showing (A) a hiatal hernia, (B) erosive gastropathy, and (C) an intact Nissen fundoplication. |

Table 1: Indications for Transthoracic Hiatal Hernia Repair | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Preoperative Planning

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree