Thrombolysis for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in the Emergency Department

Joshua M. Kosowksy

Overview

Patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) comprise the population at highest risk among patients with chest pain who present to the emergency department (ED). These patients require not only prompt diagnosis and treatment, but also often need immediate stabilization. The advent of highly effective, time-dependent treatment for STEMI makes the application of critical pathways to this population especially appropriate.

Initial ED Evaluation

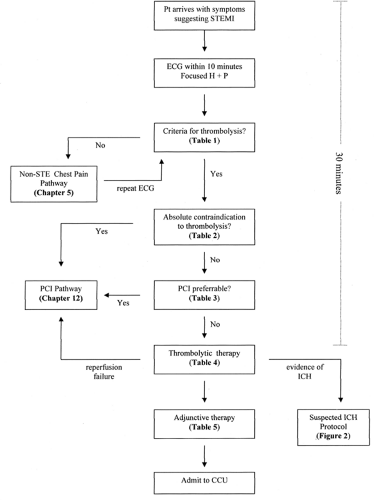

All patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of STEMI should undergo rapid evaluation for possible reperfusion therapy (Fig. 6-1 and Table 6-1). Among patients with suspected STEMI and without contraindications, the prompt use of reperfusion therapy is associated with improved survival (1).

The delay from patient arrival at the ED to initiation of thrombolytic therapy should be less than 30 minutes; alternatively, if percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is chosen, the delay from patient arrival at the ED to balloon inflation should be less than 90 minutes (2). Because there is not an interval considered to be a threshold effect for the benefit of shorter times to reperfusion, these goals should not be understood as “ideal” times, but rather as the longest times considered acceptable. On the other hand, these goals may not be relevant for patients with an appropriate reason for delay, such as uncertainty about the diagnosis, need for evaluation and treatment of other life-threatening conditions, or delays associated with the patient’s informed choice to have more time to consider the decision.

The history taken in the ED must be thorough enough to establish the likelihood of STEMI, but should be obtained expeditiously so as not to delay implementation of reperfusion therapy. It is important to consider that the differential diagnosis may include conditions that can be exacerbated by thrombolysis and anticoagulation. For example, severe tearing pain radiating directly to the back should raise the suspicion of aortic dissection, and appropriate studies should be undertaken.

Patients should be questioned about previous bleeding problems, history of ulcer disease, cerebral vascular accidents, unexplained anemia, or melena. In addition, patients should be asked about previous ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. The use of antiplatelet, antithrombin, and thrombolytic agents as part of the treatment for STEMI will exacerbate any underlying bleeding risks. Hypertension should be assessed, because chronic, severe, poorly controlled hypertension and severe uncontrolled hypertension on presentation are relative contraindications to thrombolytic therapy (Table 6-2).

The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is critical to the decision pathway because of strong evidence that ST-segment elevation identifies patients who benefit from reperfusion therapy (3). A 12-lead ECG should be performed and shown to an experienced emergency physician within 10 minutes of ED arrival on all patients with symptoms suggestive of STEMI. If the initial ECG is not diagnostic, the patient remains symptomatic, and there is a high clinical suspicion for STEMI, serial ECGs at 5- to 10-minute intervals should be performed. For patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB) not known to be new, bedside echocardiography may be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis of STEMI. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, PCI may, in fact, be preferable to thrombolytic therapy (see later discussion).

Most clinical trials have demonstrated the potential for functional, clinical, and mortality benefits only when thrombolytic therapy is given within 12 hours. However, it is reasonable to administer therapy to patients with 12 to 24 hours of continuing symptoms who meet ECG criteria for thrombolysis.

Thrombolysis Versus PCI

Controversy remains about which form of reperfusion therapy is superior in particular clinical settings. Part of the uncertainty derives from the continual introduction of new agents, devices, and strategies, which quickly make previous studies less relevant to contemporary practice. As a result, the evidence base regarding the best approach to reperfusion therapy is somewhat dynamic.

The availability of interventional cardiology facilities is a key determinant of whether PCI can be provided. For facilities that can offer PCI, the literature generally suggests that this approach is superior to pharmacological reperfusion (4) (although many of the trials comparing pharmacological and PCI

strategies were conducted before the advent of more recent strategies). Still, not all laboratories can provide prompt, high-quality primary PCI with the staffing required for 24-hour coverage. Even when round-the-clock coverage is available, the volume of cases in the laboratory may be insufficient for the team to acquire and maintain skills required for rapid PCI reperfusion strategies.

strategies were conducted before the advent of more recent strategies). Still, not all laboratories can provide prompt, high-quality primary PCI with the staffing required for 24-hour coverage. Even when round-the-clock coverage is available, the volume of cases in the laboratory may be insufficient for the team to acquire and maintain skills required for rapid PCI reperfusion strategies.

Patient-specific factors also come into play. For example, longer duration of symptoms at presentation tends to favor a PCI strategy, because the ability to produce a patent infarct artery is much less dependent on symptom duration in patients undergoing PCI than in patients undergoing thrombolysis (5). Also, when estimated mortality is extremely high, as is the case in patients with cardiogenic shock, the evidence clearly favors a PCI strategy (6).

The option of transferring patients to another facility for PCI raises additional considerations. Delays in door-to-balloon time versus door-to-needle time of more than 60 minutes because of interhospital transfer appear to negate any mortality benefit of primary PCI over immediate thrombolysis (7,8). At the same time, the DANAMI-2 trial found that patients had better composite outcomes when transferred for PCI within 2 hours of presentation than when treated with thrombolytics at local hospitals without PCI capabilities (9). On the basis of these and other studies, the 2004 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guidelines recommend that if PCI capability is not accessible within 90 minutes, STEMI patients should undergo thrombolysis unless contraindicated.

Facilitated PCI refers to a strategy of initiating thrombolytic

therapy prior to PCI, particularly when a delay to PCI is antici-pated. Theoretical advantages include earlier time to reperfusion, improved patient stability, greater procedural success rates, and higher thrombosis in myocardial infarction flow rates. Unfortunately, recent studies have not demonstrated any benefit in reducing infarct size or improving patient outcomes (10,11,12).

therapy prior to PCI, particularly when a delay to PCI is antici-pated. Theoretical advantages include earlier time to reperfusion, improved patient stability, greater procedural success rates, and higher thrombosis in myocardial infarction flow rates. Unfortunately, recent studies have not demonstrated any benefit in reducing infarct size or improving patient outcomes (10,11,12).

Table 6-1. Criteria for Thrombolysis in Stemi | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Given the current state of the literature, one cannot state definitively that a particular reperfusion approach is superior for all patients, in all clinical settings, at all times of day (Table 6-3). What is most important is that some type of reperfusion therapy be selected for every appropriate patient with STEMI. Case-by-case determinations run the risk of delaying reperfusion by unnecessarily confounding the decision-making process. Instead, the choice of strategy is typically made on the basis of a predetermined, institution-specific protocol that represents a collaborative effort from cardiologists, emergency physicians, nurses, and other appropriate personnel. For noninterventional hospitals, this may entail formal agreements allowing the expeditious transfer of patients to the nearest appropriate interventional facility. In truly complex cases that are not covered directly by an agreed-on protocol, immediate cardiology consultation is advisable.

Choice of Thrombolytic Agent

Over the past two decades, various thrombolytic regimens have been approved for use in STEMI, and each has its strengths and weaknesses (Table 6-4). On the whole, however, the differences among regimens are relatively minor. The literature suggests that accelerated-dose alteplase with intravenous heparin provides a mortality advantage over streptokinase, although it is substantially more expensive and confers a slightly greater risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (13). Single-bolus, weight-based TNK (tenecteplase) and double-bolus reteplase are associated with virtually identical rates of mortality and similar rates of ICH to accelerated-dose alteplase (14). TNK has been shown to have a 20% lower risk of non-ICH major bleeding. Combination therapy with abciximab and half-dose reteplase or tenecteplase can be considered for prevention of reinfarction and other complications of STEMI in selected patients: anterior location of MI, age less than 75 years, and no risk factors for bleeding (15,16). However, this regimen is associated with a

doubling in the risk of major bleeding and is more complicated, hence it is not widely used. Once again, making the appropriate decision to administer a thrombolytic without delay is generally more important than which regimen is chosen. Therefore, the choice of thrombolytic regimen is often determined by protocol at the institutional level.

doubling in the risk of major bleeding and is more complicated, hence it is not widely used. Once again, making the appropriate decision to administer a thrombolytic without delay is generally more important than which regimen is chosen. Therefore, the choice of thrombolytic regimen is often determined by protocol at the institutional level.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree