Chapter 15 Thoracic organ transplantation

HISTORY

The 1980s heralded a new era in thoracic organ transplantation with the first long-term survivors of heart-lung (Reitz et al 1982), single lung (Cooper et al 1987) and double lung (Patterson et al 1988) transplantation. The advent of ciclosporin (Borel 1980) as the principal immunosuppressant, with a greater ability to prevent acute rejection, was considered pivotal to improved survival outcomes.

From the late 1980s to the mid 1990s there was steady growth in both the overall numbers of transplants performed and the number of centres performing them. These numbers have now stabilized and reflect the ongoing shortage of donor organs. Internationally, over 4000 heart transplants, 60 heart-lung transplants and 1600 lung transplants are performed in adults each year (Taylor et al 2005, Trulock et al 2005). The number of paediatric transplants is much smaller, with approximately 350 heart transplants, 10 heart-lung transplants, and 80 lung transplants performed (Boucek et al 2005).

Over the last 30 years, significant advances have been made in all aspects of the care of thoracic organ transplant recipients. There have been improvements in operative techniques, organ preservation and cross matching. New, less toxic immunosuppressants have been developed. There is a greater understanding of immunology and a greater ability to bridge to transplant with mechanical support devices. Current survival outcomes for patients receiving heart transplantation are more favourable than for lung transplantation with 81%, 67% and 48% survival at 1, 5 and 10 years compared with 76%, 49% and 24%, respectively (Taylor et al 2005, Trulock et al 2005). Outcomes in children are similar to those in adults.

INDICATIONS FOR TRANSPLANTATION

Thoracic organ transplantation is indicated in patients with various end-stage diseases where survival is limited and quality of life poor (Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Indications for thoracic organ transplantation

| Heart | |

| Heart-lung | |

| Single lung | |

| Bilateral lung |

Heart transplant

The distribution of indications for cardiac transplantation has not changed significantly over the last 10 years (Taylor et al 2005). The most common indications in adults continue to be ischaemic and non-ischaemic heart failure (45% each). Valvular disease (3–4%), adult congenital heart disease (2%) and allograft failure requiring retransplantation (2%) make up the remaining indications. What has changed is the increasing number of patients bridged to transplant using intravenous inotropic support (48%) and some type of mechanical circulatory support (21%) with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Lung transplant

The main indications of adult lung transplant are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (38%), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (17%), cystic fibrosis (17%) and a 1-antitrypsin deficiency emphysema (9%). The most common indications in childhood differ by age group. In infants, congenital heart disease is the most common indication (47%). In older children, cystic fibrosis (72%), primary pulmonary hypertension (10%) and retransplantation (6%) are the main indications. Interstitial lung disease, pulmonary vascular disease and bronchiolitis obliterans less commonly lead to transplantation in children (Boucek et al 2005). Lung transplant is rarely appropriate in critically ill patients in desperate clinical situations (i.e. intubated in the intensive care unit).

Heart-lung transplant

Primary pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary hypertension associated with Eisenmenger’s syndrome/congenital heart disease have been the main indications for heart-lung transplantation in adults and children (see Table 15.1).

Contraindications to transplantation

Patients with comorbidities that may seriously compromise the outcome of transplantation are excluded. There are few absolute contraindications to thoracic organ transplantation, and consideration of relative contraindications is usually made on an individual basis (Box 15.1).

ASSESSMENT

Potential recipients are assessed by an experienced multidisciplinary team at a transplant centre (Box 15.2). This process involves extensive physiological, functional and psychological assessment in order to:

evaluate the severity of cardiac and/or pulmonary dysfunction (e.g. pulmonary function testing, per-fusion scan, echocardiography, gated blood pool scan)

evaluate the severity of cardiac and/or pulmonary dysfunction (e.g. pulmonary function testing, per-fusion scan, echocardiography, gated blood pool scan) identify previous exposure to potentially complicating infection: cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

identify previous exposure to potentially complicating infection: cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)Physiotherapy assessment

Musculoskeletal assessment

The screening assessment should include:

A more in-depth assessment is required if musculoskeletal abnormalities are found. Structural and postural thoracic kyphosis, shoulder pathologies (rotator cuff impingement syndromes), shortened calf, hamstrings and iliopsoas muscles and reduced muscle bulk are commonly seen in thoracic transplant candidates.

Exercise capacity

six-minute walk test (6MWT)

six-minute walk test (6MWT)—distance walked, response to exercise (i.e. SpO2, HR, BP, symptoms), limitation to exercise

—general guidelines: In adults a 6MWT distance <300–400 m is suggested as appropriate for listing for both heart and lung transplantation (Kadikar et al 1997, Raul et al 1998), whereas in children desaturation on 6MWT is a better predictor of survival (Aurora et al 2000).

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Heart transplantation

Orthotopic heart transplantation

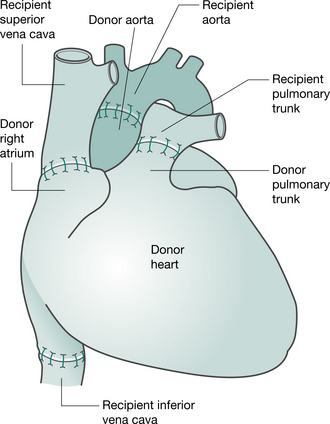

Preparation of the heart (and heart-lung) transplant recipient is similar to that for any patient undergoing cardiac surgery (anaesthesia, median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass). When the donor heart is present in the recipient theatre and has passed a final inspection, the recipient heart is removed, by incising the atria, pulmonary artery and aorta. The posterior walls of both atria, including the sinoatrial node, are left intact. The donor heart is sutured in place. The anastomoses join the recipient and donor atria, the pulmonary arteries and the aortas (Keogh et al 1986) (Fig. 15.1). More recently, the bicaval anastomosis technique has been carried out at some centres. Potential advantages of this technique, which maintains the anatomic integrity of the donor right atrium, include a reduction in the incidence and severity of tricuspid regurgitation, preservation of right atrial function and facilitation of restoration of sinus rhythm (Morgan & Edwards 2005).

Heterotopic heart transplantation

Heterotopic transplantation is rarely performed, but is occasionally indicated in patients with cardiac dysfunction resulting in severe pulmonary hypertension. In this ‘piggyback’ procedure the recipient heart is left in place and the donor heart is positioned in the right chest. The donor heart is connected to the recipient’s in parallel by anastomoses made between the two hearts at the atria, pulmonary arteries and aortas (Newcomb et al 2004). Both hearts contribute to the cardiac output and share the work required to overcome the increased pulmonary pressures (Newcomb et al 2004, Novitzky et al 1983). Inherent problems with this procedure include pulmonary compression of the recipient’s right lung, difficulty obtaining endomyocardial biopsy and need for anticoagulation.

Lung transplantation

Double lung/bilateral sequential lung transplantation

The most commonly performed double lung transplantation (DLT) procedure is bilateral sequential lung transplantation. The early experiences of double lung transplantation involved the implantation ‘en bloc’ of both lungs via a median sternotomy, utilizing an omental wrap to secure the tracheal anastomosis (Patterson et al 1988). In an effort to avoid the high incidence of airway complications associated with the original procedure, the technique of bilateral sequential lung transplantation via bilateral anterolateral thoracotomies through the fourth or fifth intercostal space connected with a transverse sternotomy or ‘clamshell incision’ is now preferred. Mobilization and pneumonectomy of the native lung and the implantation of the lung graft are conducted in the same manner as described for single lung transplantation.

Heart-lung transplantation

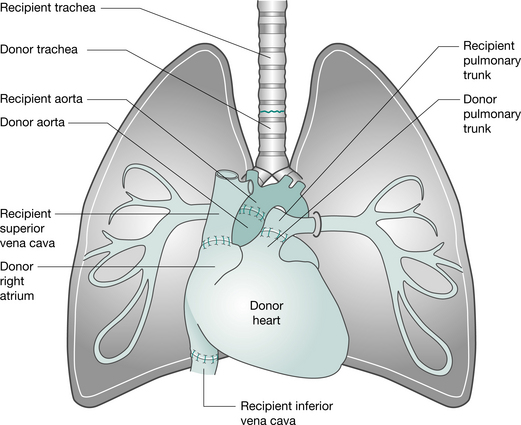

This operation can be performed via a median sternotomy or a clamshell incision. Following the institution of cardiopulmonary bypass, the heart and lungs are excised separately, allowing identification and protection of the phrenic, recurrent laryngeal and vagus nerves. The heart is removed, leaving the posterior wall of the right atrium. The left and then right lungs are removed (following stapling of the bronchi, to minimize the risk of contaminating the area) and the trachea is divided. The donor heart-lung block is implanted, starting with the tracheal, then the atrial and aortic anastomoses (Fig. 15.2). Ventilation is established (ensuring the patency of the airway anastomosis) and the heart resuscitated (Jamieson et al 1984). To improve donor availability, recipients with primary lung disease who receive heart-lung blocks (e.g. patients with cystic fibrosis) may be asked to donate their hearts to a cardiac patient. This is termed the ‘domino’ procedure.

Other lung techniques

The split-lung technique (Couetil et al 1997) utilizes individual lobes from the donor. It may be indicated if there is localized pathology in one lobe of the donor lung or if the donor organ is larger than expected.

Living donor lobar lung transplantation (Date et al 2003, Starnes et al 1999) involves two donors (usually relatives) each donating a single lobe (usually lower lobe) for bilateral lung transplantation. The recipient is usually critically ill and cannot wait for cadaveric transplantation. It is most often performed in adolescents or young adults with cystic fibrosis.

KEY CONCEPTS

Organ donation

Organ donation for transplantation is performed in the setting of brain death. Brain death is defined as a complete and irreversible cessation of brain activity. The main causes are severe head injury from physical trauma, often from road traffic accidents and from subarachnoid haemorrhage. In most countries, consent from family members or next-of-kin is required. It is normal practice for consent to be sought even if the brain-dead individual had expressed the wish to donate. In some countries (e.g. Spain, Belgium, Poland, France) potential donors are presumed to have given consent, although some jurisdictions allow opting out from the system. Once consent is obtained, the non-living donor is kept on ventilatory support until the organs have been surgically removed. The donor is given expert medical and nursing care to optimize organ performance. Physiotherapists sometimes assist in the removal of retained lung secretions and help to optimize ventilation (Gabbay et al 1999).

Timing of organ retrieval and implantation is important and necessitates a high level of coordination between the donor and recipient transplant teams. Organ procurement occurs at the hospital where the donor is managed. The organ is kept in preservation solution while it is transported to the transplant centre for implantation into the selected recipient. Most cardiac teams aim for an ischaemic time of less than 4 hours, from the time of cross-clamping the aorta in the donor to reperfusing the organ in the recipient. Lung teams aim for less than 8 hours. Longer ischaemic times are associated with poorer early graft function (Del Rizzo et al 1999, Thabut et al 2005).

The recipient team selects the appropriate recipient based upon:

Immunosuppression and rejection

Immunosuppressants have a number of specific side effects, which are listed in Table 15.2. It is important that physiotherapists working with thoracic organ transplant recipients are familiar with these side effects. Many agents impact on the musculoskeletal system and may cause bone morbidities such as avascular necrosis, osteoporosis and reduced tissue healing. Side effects of some agents affect the patient’s ability to participate in exercise training (e.g. hypertension, nausea) or have practical implications (e.g. fine hand tremor affecting writing ability and difficulty fitting into footwear due to fluid retention).

Table 15.2 Immunosuppression and side effects

| Immunosuppressant |

|---|