Thoracic Aortic Atherosclerosis

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

In developed countries, atherosclerosis occurs in virtually every aorta, beginning in the second to third decades, with more rapid progression in the presence of genetic predisposition and acquired risk factors. Aortic atherosclerosis correlates with disease burden in other major arteries such as coronaries and carotids, with several histologic similarities. Autopsy studies have shown similar atherosclerotic plaque burden across arterial beds in a single patient.1 In the aorta, there tends to be increasing atherosclerosis distally, with the formation of ulcerative plaques and aneurysms most common in the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries.

Epidemiologic studies have established the risk factors of age, male sex, obesity, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia for the development of aortic atherosclerosis. Those studies also highlighted the importance of reducing risk factors in decreasing the extent, severity, and complications of atherosclerosis. Results from the Pathological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study, a long-term cohort to identify lesions in patients 15 to 34 years old, found that fatty streaks begin earlier in the aorta compared to the coronaries and that the thoracic aorta are usually more involved by atherosclerosis than the abdominal aorta, but advanced lesions were more prevalent on the abdominal than in the thoracic aorta.2

Gross Findings

In contrast to the coronary arteries, aortic atherosclerosis has largely been classified and staged based on gross findings. The earliest lesion in the aorta is the fatty streak (presence in humans as early as in the first decade of life), which is seen as a yellowish, slightly elevated plaque on the surface of the intima. Fatty streaks in the aorta correspond roughly to intimal xanthomas, as described histologically in the coronary arteries. They usually start in the dorsal aorta, close to the ostia of the intercostal arteries, but in the abdominal aorta, close to the origin of the renal arteries, there is accumulation of fatty streaks in the ventral surface.

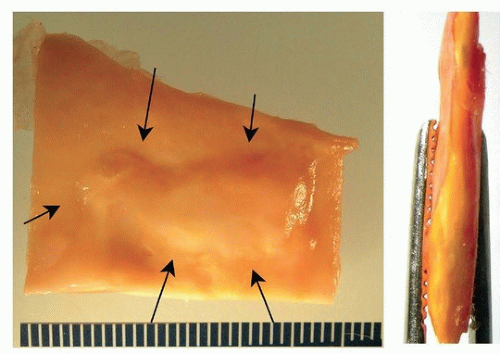

Occurring later than fatty streaks are raised lesions, or fibrous plaques. On cross section, they are often lipid rich (Fig. 191.1).

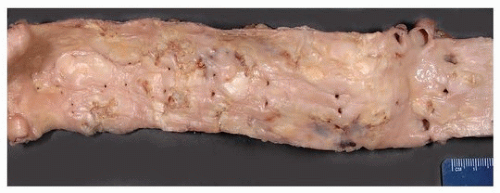

The characteristics of advanced aortic plaques are similar to those of the coronary arteries and include rupture, thrombosis, calcification, and aneurysm formation (Figs. 191.2, 191.3, 191.4). Because of the large caliber of the aorta, however, ruptured plaques are incidental findings and do not usually represent risk of embolization and death. Advanced lesions may, however, weaken the aortic media and result in aneurysm formation.

Microscopic Findings

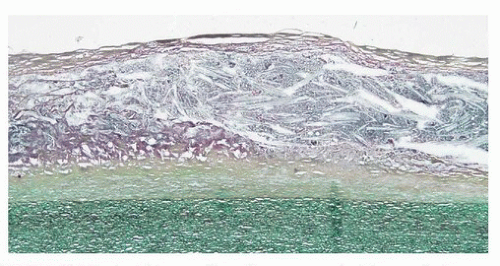

Fatty streaks are histologically similar to intimal xanthomas of the coronaries. There is intracellular accumulation of lipids in macrophages and smooth muscle cells, forming foam cells. Fibrous plaques denote the formation of necrotic core with overlying fibrous cap (Fig. 191.5). Hemorrhage into plaque is common (Fig. 191.6). Ulcerated lesions result from rupture of a thin fibrous cap with luminal thrombus. Calcification of aortic atherosclerosis may be a prominent feature in the absence of atheroma, and progresses from a plate of intimal calcification to rupture of the calcified area and formation of calcified nodule.

Complications of Aortic Atherosclerosis

Although prevalent among all age groups in developed countries, aortic atherosclerosis remains asymptomatic until complications develop. Complications occur when there are advanced, ulcerative lesions. Symptoms result from aneurysmal change, especially in the abdominal aorta, with predisposition to rupture; embolic disease, from aortic arch vessels into the cerebral circulation, or abdominal aorta into visceral arteries; ulceration and intramural hematoma formation in the thoracic aorta; extension into mesenteric and renal arteries, with occlusion

of these vessels and ischemic injury to the bowel or kidneys; and aortoiliac occlusive disease, without aneurysm formation. Occlusive aortoiliac disease may result in Leriche syndrome, characterized by impotence, claudication of the buttocks and thighs, leg weakness, and lack of palpable femoral pulses.

of these vessels and ischemic injury to the bowel or kidneys; and aortoiliac occlusive disease, without aneurysm formation. Occlusive aortoiliac disease may result in Leriche syndrome, characterized by impotence, claudication of the buttocks and thighs, leg weakness, and lack of palpable femoral pulses.

FIGURE 191.2 ▲ Moderate atherosclerosis, thoracic aorta. Raised lesions, with scattered ulcerated plaques, cover about 50% of the intima. The intercostal artery ostia are evident. |

FIGURE 191.3 ▲ Severe atherosclerosis, thoracic aorta. Fibrous plaques, many of which are ulcerated, cover most of the intima. |

FIGURE 191.4 ▲ Severe atherosclerosis, thoracic aorta. In this example, there is early aneurysm formation. Note the ostia of the intercostal arteries indicating thoracic location. |

FIGURE 191.5 ▲ Thin-cap fibroatheroma, aorta. The media is below, and the fibroatheromatous core above. Movat pentachrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|