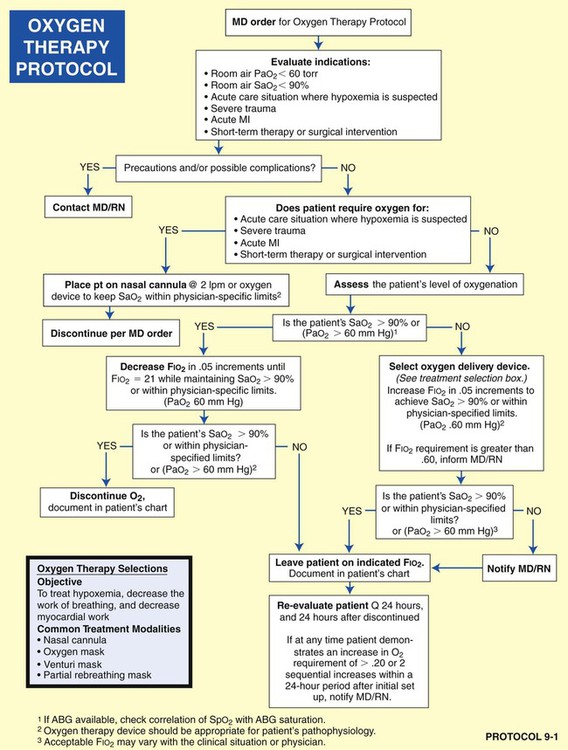

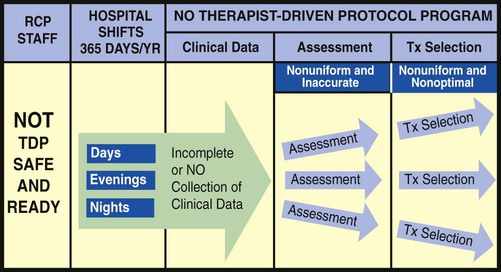

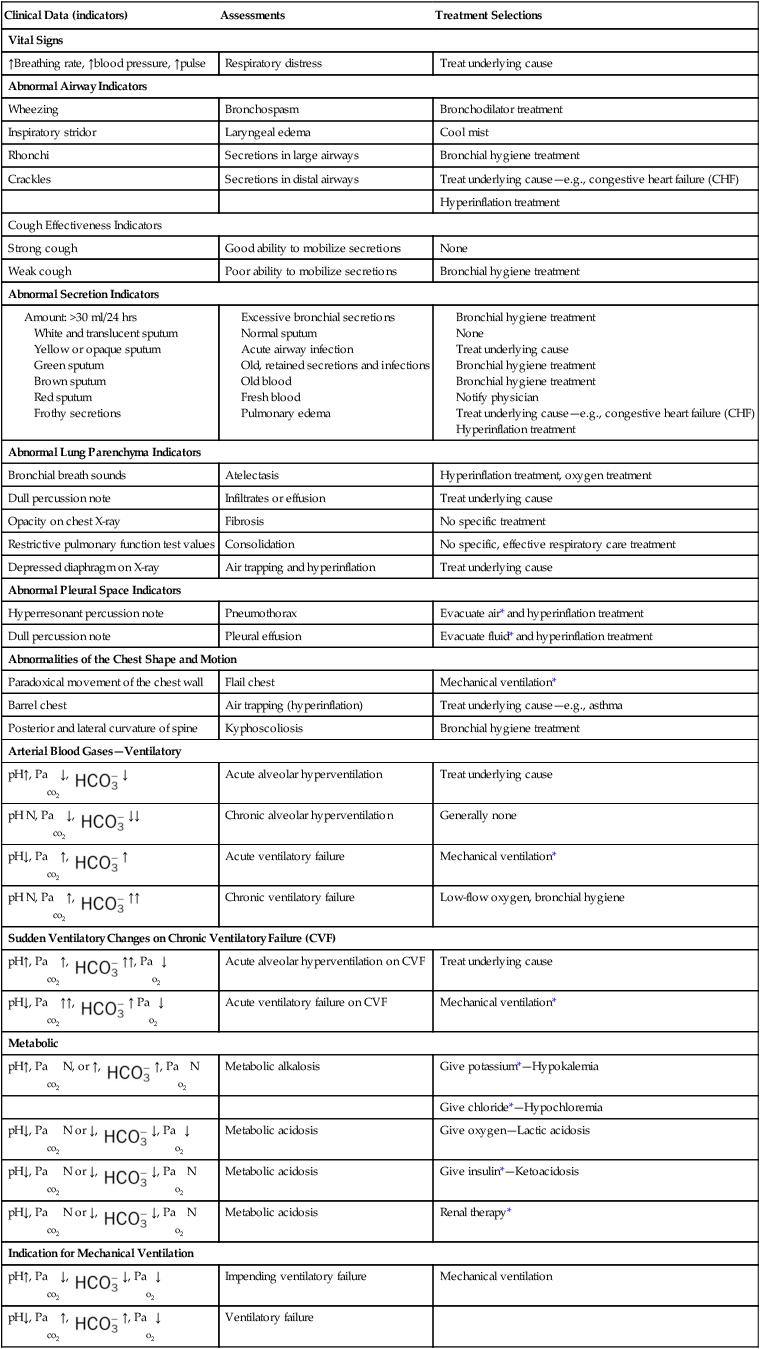

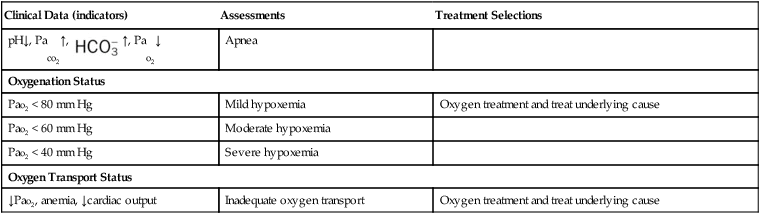

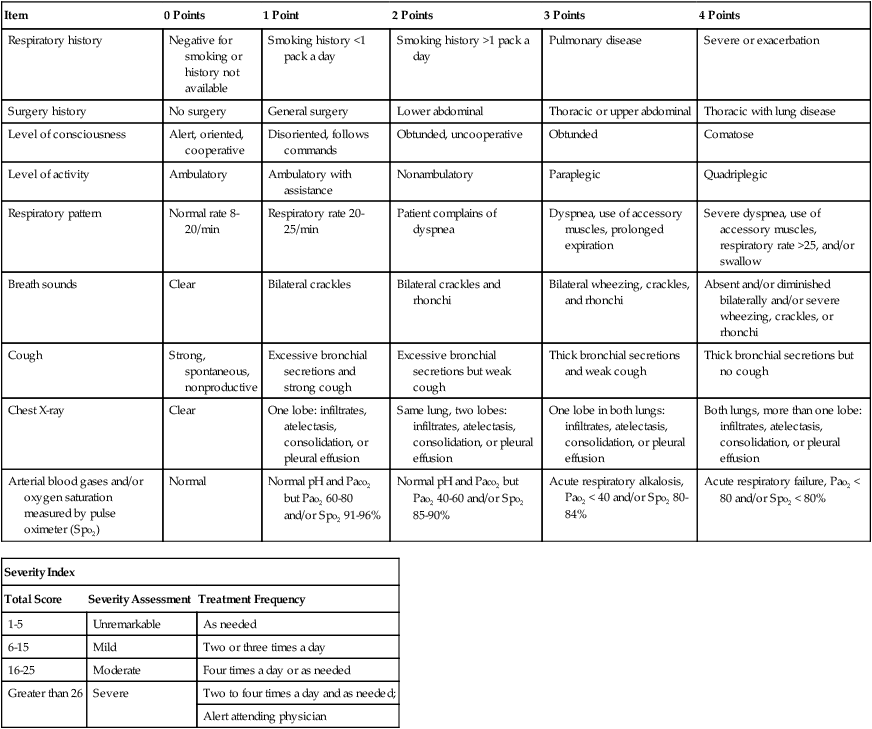

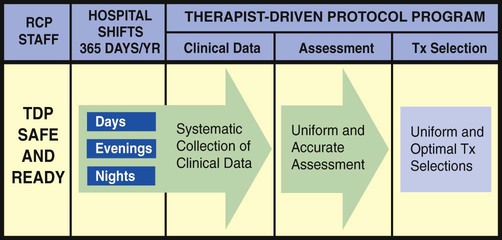

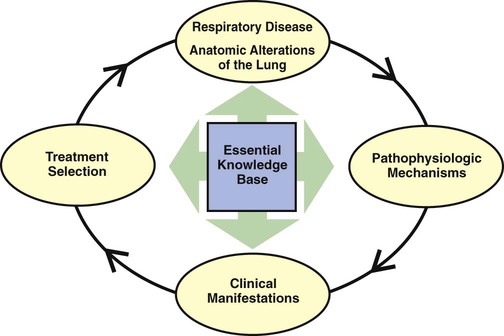

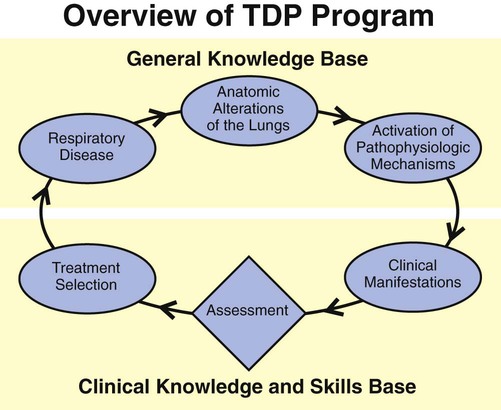

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • Describe the Therapist-Driven Protocol (TDP) program and the role of the respiratory care practitioner. • Discuss the knowledge base required for a successful TDP program. • Explain the assessment process skills required for a successful TDP program, and include the following: • The clinical manifestations, assessments, and treatment selections made by the respiratory care practitioner • The frequency at which a respiratory therapy modality can be determined in response to a severity assessment • Describe the following essential cornerstone respiratory protocols for a successful TDP program: • Bronchopulmonary hygiene therapy protocol • Lung expansion therapy protocol • Aerosolized medication therapy protocol • Mechanical ventilation protocol • Mechanical ventilation weaning protocol • Describe ventilatory management in catastrophes. • List the following common anatomic alterations of the lungs: • Increased alveolar-capillary membrane thickness • Excessive bronchial secretions • Distal airway and alveolar weakening • Analyze the clinical scenarios—chain of events—activated by the common anatomic alterations of the lungs, and include the following: • Anatomic alterations of the lungs • Pathophysiologic mechanisms activated • Treatment protocols used to correct the problem • Identify the most common anatomic alterations associated with the respiratory disorders presented in this textbook. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. • Deliver individualized diagnostic and therapeutic respiratory care to patients • Assist the physician with evaluating patients’ respiratory care needs and optimize the allocation of respiratory care services • Determine the indications for respiratory therapy and the appropriate modalities for providing high-quality, cost-effective care that improves patient outcomes and decreases length of stay • Empower respiratory care practitioners to allocate care using sign- and symptom-based algorithms for respiratory treatment Unfortunately, the implementation of TDPs throughout the United States has been slow. In 2008 the AARC Protocol Implementation Committee conducted a survey to evaluate the barriers to protocol implementation. Over 450 respiratory managers responded to the survey. Despite the overwhelming evidence that protocols clearly improve outcomes and reduce cost, the survey showed that less than 50% of respiratory care was provided by protocols. About 75% of the respondents had at least one protocol in operation. The majority of the hospitals did not have a comprehensive program in place. According to the managers, the medical directors, managers of the department, nurses, and administrators were not perceived as barriers. The biggest barrier to the implementation of protocols was perceived to be the medical staff. The primary reason for the medical staff’s resistance was perceived to be that “staff therapists did not have the skills (e.g., assessment skills) to function under protocols.” The AARC Protocol Implementation Committee states that “[this] perception must change… .”* The essential components of a good TDP program do not come easy. This is because a strong TDP program promises that the respiratory care practitioner, who is identified as “TDP safe and ready,” be qualified to (1) systematically collect the appropriate clinical data, (2) formulate a uniform and accurate assessment, and (3) select a uniform and optimal treatment within the limits set by the protocol (Figure 9-1). The converse, however, is also true: When the respiratory care practitioner is not “TDP safe and ready,” the collection of clinical data is not done at all or is incomplete. As a result, nonuniform or inaccurate assessments are made, resulting in nonuniform or inaccurate treatment selections (Figure 9-2). This inappropriate and ineffective type of respiratory therapy leads to the misallocation of care, the administration of unneeded care, and—most important—the nonprovision of needed patient care. The bottom line is poor-quality patient care and unnecessary costs. To be sure, the development and implementation of a strong TDP program require some fundamental knowledge, training, and practice, but the benefits are worth the price. The essential components of a good TDP program are discussed in the following paragraphs. As shown in Figure 9-3, the essential knowledge base for a successful TDP program includes (1) the anatomic alterations of the lungs caused by common respiratory disorders, (2) the major pathophysiologic mechanisms activated throughout the respiratory and cardiac systems as a result of the anatomic alterations, (3) the common clinical manifestations that develop as a result of the activated pathophysiologic mechanisms, and (4) the treatment modalities used to correct them. In other words, the clinical manifestations demonstrated by the patient do not arbitrarily appear but are the result of anatomic lung alterations and pathophysiologic events. Using the knowledge base described above, the respiratory care practitioner must also be competent in performing the actual assessment process. This means that the practitioner can (1) quickly and systematically gather the clinical information demonstrated by the patient, (2) formulate an accurate assessment of the clinical data (i.e., identify the cause and severity of the problem), (3) select an optimal treatment modality, and (4) document this process quickly, clearly, and precisely. In the clinical setting, the practice—and mastery—of the assessment process is absolutely central and essential to the success of a good TDP program (Figure 9-4). In other words, immediately after the respiratory care practitioner identifies the appropriate clinical manifestations (clinical indicators), an assessment of the data must be performed, and a treatment plan must be formulated. For the most part the assessment is primarily directed at the anatomic alterations of the lungs that are causing the clinical indicators (e.g., bronchospasm) and the severity of the clinical indicators. For example, an appropriate assessment for the clinical indicator of wheezing might be bronchospasm—the anatomic alteration of the lungs. If the practitioner assesses the cause of the wheezing correctly as bronchospasm, then the correct treatment selection would be a bronchodilator treatment from the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (see Protocol 9-4, page 122). If, however, the cause of the wheezing is correctly assessed to be excessive airway secretions, then the appropriate treatment plan would entail a specific treatment modality under the Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, such as cough and deep breathing or chest physical therapy (see Protocol 9-2, page 120). Table 9-1 illustrates common clinical manifestations (i.e., clinical indicators), assessments, and treatment selections routinely made by the respiratory care practitioner. TABLE 9-1 *These procedures should be performed only as ordered by the physician. The frequency at which a respiratory therapy modality is to be administered is just as important as the correct selection of a respiratory therapy treatment. Often the frequency of treatment must be up-regulated or down-regulated on a shift-by-shift, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute, or even (in life-threatening situations) second-to-second basis. Such frequency changes must be made in response to a severity assessment. In a good TDP program, the well-seasoned respiratory care practitioner routinely and systematically documents many severity assessments throughout each working day. For the new practitioner, however, a predesigned Severity Assessment Rating Form may be used to enhance this important part of the assessment process. One excellent, semiquantitative method of accomplishing this is illustrated in Table 9-2. The clinical application of this severity assessment is provided in the following case example. TABLE 9-2 Respiratory Care Protocol Severity Assessment

The Therapist-Driven Protocol Program and the Role of the Respiratory Care Practitioner

Introduction

The “Knowledge Base” Required for a Successful Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

The “Assessment Process Skills” Required for a Successful Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

Clinical Data (indicators)

Assessments

Treatment Selections

Vital Signs

↑Breathing rate, ↑blood pressure, ↑pulse

Respiratory distress

Treat underlying cause

Abnormal Airway Indicators

Wheezing

Bronchospasm

Bronchodilator treatment

Inspiratory stridor

Laryngeal edema

Cool mist

Rhonchi

Secretions in large airways

Bronchial hygiene treatment

Crackles

Secretions in distal airways

Treat underlying cause—e.g., congestive heart failure (CHF)

Hyperinflation treatment

Cough Effectiveness Indicators

Strong cough

Good ability to mobilize secretions

None

Weak cough

Poor ability to mobilize secretions

Bronchial hygiene treatment

Abnormal Secretion Indicators

Abnormal Lung Parenchyma Indicators

Bronchial breath sounds

Atelectasis

Hyperinflation treatment, oxygen treatment

Dull percussion note

Infiltrates or effusion

Treat underlying cause

Opacity on chest X-ray

Fibrosis

No specific treatment

Restrictive pulmonary function test values

Consolidation

No specific, effective respiratory care treatment

Depressed diaphragm on X-ray

Air trapping and hyperinflation

Treat underlying cause

Abnormal Pleural Space Indicators

Hyperresonant percussion note

Pneumothorax

Evacuate air* and hyperinflation treatment

Dull percussion note

Pleural effusion

Evacuate fluid* and hyperinflation treatment

Abnormalities of the Chest Shape and Motion

Paradoxical movement of the chest wall

Flail chest

Mechanical ventilation*

Barrel chest

Air trapping (hyperinflation)

Treat underlying cause—e.g., asthma

Posterior and lateral curvature of spine

Kyphoscoliosis

Bronchial hygiene treatment

Arterial Blood Gases—Ventilatory

pH↑, Paco2↓,  ↓

↓

Acute alveolar hyperventilation

Treat underlying cause

pH N, Paco2↓,  ↓↓

↓↓

Chronic alveolar hyperventilation

Generally none

pH↓, Paco2↑,  ↑

↑

Acute ventilatory failure

Mechanical ventilation*

pH N, Paco2↑,  ↑↑

↑↑

Chronic ventilatory failure

Low-flow oxygen, bronchial hygiene

Sudden Ventilatory Changes on Chronic Ventilatory Failure (CVF)

pH↑, Paco2↑,  ↑↑, Pao2↓

↑↑, Pao2↓

Acute alveolar hyperventilation on CVF

Treat underlying cause

pH↓, Paco2↑↑,  ↑ Pao2↓

↑ Pao2↓

Acute ventilatory failure on CVF

Mechanical ventilation*

Metabolic

pH↑, Paco2 N, or ↑,  ↑, Pao2 N

↑, Pao2 N

Metabolic alkalosis

Give potassium*—Hypokalemia

Give chloride*—Hypochloremia

pH↓, Paco2 N or ↓,  ↓, Pao2↓

↓, Pao2↓

Metabolic acidosis

Give oxygen—Lactic acidosis

pH↓, Paco2 N or ↓,  ↓, Pao2 N

↓, Pao2 N

Metabolic acidosis

Give insulin*—Ketoacidosis

pH↓, Paco2 N or ↓,  ↓, Pao2 N

↓, Pao2 N

Metabolic acidosis

Renal therapy*

Indication for Mechanical Ventilation

pH↑, Paco2↓,  ↓, Pao2↓

↓, Pao2↓

Impending ventilatory failure

Mechanical ventilation

pH↓, Paco2↑,  ↑, Pao2↓

↑, Pao2↓

Ventilatory failure

pH↓, Paco2↑,  ↑, Pao2↓

↑, Pao2↓

Apnea

Oxygenation Status

Pao2 < 80 mm Hg

Mild hypoxemia

Oxygen treatment and treat underlying cause

Pao2 < 60 mm Hg

Moderate hypoxemia

Pao2 < 40 mm Hg

Severe hypoxemia

Oxygen Transport Status

↓Pao2, anemia, ↓cardiac output

Inadequate oxygen transport

Oxygen treatment and treat underlying cause

Severity Assessment

Item

0 Points

1 Point

2 Points

3 Points

4 Points

Respiratory history

Negative for smoking or history not available

Smoking history <1 pack a day

Smoking history >1 pack a day

Pulmonary disease

Severe or exacerbation

Surgery history

No surgery

General surgery

Lower abdominal

Thoracic or upper abdominal

Thoracic with lung disease

Level of consciousness

Alert, oriented, cooperative

Disoriented, follows commands

Obtunded, uncooperative

Obtunded

Comatose

Level of activity

Ambulatory

Ambulatory with assistance

Nonambulatory

Paraplegic

Quadriplegic

Respiratory pattern

Normal rate 8-20/min

Respiratory rate 20-25/min

Patient complains of dyspnea

Dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, prolonged expiration

Severe dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, respiratory rate >25, and/or swallow

Breath sounds

Clear

Bilateral crackles

Bilateral crackles and rhonchi

Bilateral wheezing, crackles, and rhonchi

Absent and/or diminished bilaterally and/or severe wheezing, crackles, or rhonchi

Cough

Strong, spontaneous, nonproductive

Excessive bronchial secretions and strong cough

Excessive bronchial secretions but weak cough

Thick bronchial secretions and weak cough

Thick bronchial secretions but no cough

Chest X-ray

Clear

One lobe: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion

Same lung, two lobes: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion

One lobe in both lungs: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion

Both lungs, more than one lobe: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion

Arterial blood gases and/or oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximeter (Spo2)

Normal

Normal pH and Paco2 but Pao2 60-80 and/or Spo2 91-96%

Normal pH and Paco2 but Pao2 40-60 and/or Spo2 85-90%

Acute respiratory alkalosis, Pao2 < 40 and/or Spo2 80-84%

Acute respiratory failure, Pao2 < 80 and/or Spo2 < 80%

Severity Index

Total Score

Severity Assessment

Treatment Frequency

1-5

Unremarkable

As needed

6-15

Mild

Two or three times a day

16-25

Moderate

Four times a day or as needed

Greater than 26

Severe

Two to four times a day and as needed;

Alert attending physician

The Therapist-Driven Protocol Program and the Role of the Respiratory Care Practitioner

41, and Pa

41, and Pa