Chapter 1 The Scope of the EMG Examination

Electromyography (EMG) is a term that was first coined by Weddell et al in 1943 to describe the clinical application of needle electrode examination of skeletal muscles. Since then, and at least in North America, the nomenclature “EMG” or “clinical EMG” has been used by physicians to refer to the electrophysiologic examination of peripheral nerve and muscle that include the nerve conduction studies (NCS) as well as the needle evaluation of muscles. These terms continue to cause confusion that hinders communication among physicians and healthcare workers. Some physicians refer to the study as EMG/NCS, reserving the name EMG solely to the needle EMG evaluation and adding the term NCS to reflect the nerve conduction studies separately. Others have used the title needle EMG or needle electrode examination to reflect the needle evaluation of muscles, while keeping the term EMG to describe the entire evaluation of nerve and muscle. More recently, a nonspecific term, the “electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination,” has gained popularity to serve as an umbrella covering both the needle EMG and NCS. Other nomenclature used worldwide includes the electrophysiologic examination, which may be confused with the cardiac electrophysiological studies, and the electroneuromyographic (ENMG) examination which is the most accurate description of the study, yet unfortunately not widely used. Finally, physicians performing and interpreting these studies are called electromyographers (EMGers), electrodiagnosticians, or EDX consultants.

The EDX examination comprises a group of tests that are usually complementary to each other and often nec-essary to diagnose or exclude a neuromuscular problem (Table 1-1). These include principally the nerve conduction studies (NCS), that are sensory, motor, or mixed, and the needle EMG, sometimes referred as “conventional” or “routine” needle EMG to distinguish this test from other needle EMG studies including single fiber EMG and quantitative EMG. Also, “concentric” or “monopolar” needle EMG is sometimes utilized to reflect the type of needle electrode used. In addition to the two main components of the EMG examination, three late responses are often incorporated with the NCSs and have become an integral part of the NCSs. These include the F waves also referred to as F responses, the H reflexes also known as H responses, and the blink reflexes. Two specialized tests are often added to the routine EDX study mainly in patients with suspected neuromuscular junction disorders. These include the repetitive nerve stimulations and the single fiber EMG. Finally, a group of specialized studies that require special expertise as well as sophisticated equipment and software, used as a clinical and research tool in the assessment of the microenvironment of the motor unit, include motor unit action potential (MUAP) morphology analysis, MUAP turns and amplitudes analysis, macro EMG, motor unit number estimate (MUNE), and near-nerve recording studies.

Table 1-1 The Spectrum of Clinical Electromyography (Electrodiagnosis)

THE REFERRAL PROCESS TO THE EMG LABORATORY

Patients are referred to the EMG laboratory for EDX studies following a clinical assessment by a physician who suspects a disorder of the peripheral nervous system. For example, a patient with intermittent hand paresthesias and positive Phalen’s signs may be referred to the EMG laboratory to evaluate a possible carpal tunnel syndrome. The background and specialty of the referring physician plays a significant role in the planning and execution of the EDX study. In the experience of this author, this usually follows one of these three scenarios:

THE EMG LABORATORY PROCEDURES

Testing an Adult

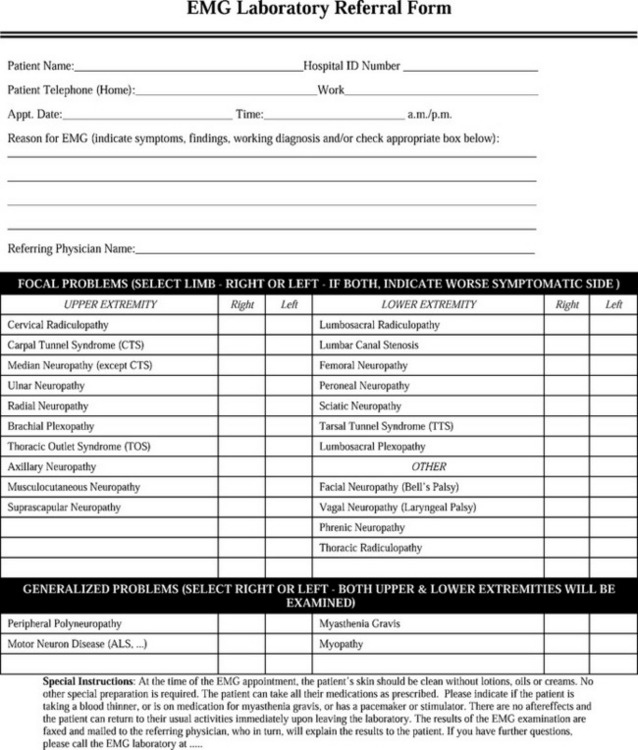

Patients referred to the EMG laboratory should have a referral form completed by the referring physician with relevant clinical information and preferably a pertinent neurological differential diagnosis (Figure 1-1). Referring physicians should also describe the EDX study to their adult patients, particularly in regard to the discomfort associated with it, without creating unnecessary heightened anxiety. If unclear about the technical details of the procedure, they should encourage their patients to contact the EMG laboratory prior to the test date, to get a verbal or written description of the procedure. Such written descriptions should be widely available in all referring physicians’ offices (Table 1-2).

Figure 1-1 A sample of the referring request for an EMG examination.

(Adapted from Katirji B. The clinical electromyography examination. An overview. Neurol Clin N Am 2002;20:291–303.)

Table 1-2 A Sample of a Descriptive Explanation of the EMG Examination to be Given to Patients before Undergoing Testing