(1)

Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

Late one evening, in the springtime of 1452, in the low foothills of Montalbano, northwestern Tuscany, an illegitimate baby boy was born to a local farmer’s daughter called Caterina. The child was Leonardo da Vinci. He was conceived, perhaps, as the result of a brief romantic entanglement between the relatively affluent son of an old Vinci family of notaries (Ser Piero da Vinci) and a woman of lower birth, about whom very little is really known. He would grow into the original Renaissance man, whose good looks, charm, and charisma became a legend in his own time. Furthermore and pertinent to our story, he would become a contemporary icon for both science and the arts.

Wisdom is the daughter of experience

(Forster III; 14r.)

Late one evening, in the springtime of 1452, in the low foothills of Montalbano, northwestern Tuscany, an illegitimate baby boy was born to a local farmer’s daughter called Caterina. The child was Leonardo da Vinci. He was conceived, perhaps, as the result of a brief romantic entanglement between the relatively affluent son of an old Vinci family of notaries (Ser Piero da Vinci) and a woman of lower birth, about whom very little is really known. He would grow into the original Renaissance man, whose good looks, charm, and charisma became a legend in his own time. Furthermore and pertinent to our story, he would become a contemporary icon for both science and the arts.

Although very little is known about his early life, we do have the exact date and time of his birth. A German research worker, Dr. Emile Möller, discovered it in the state archives in Florence in the 1930s. Möller discovered the details of the birth on the back of an old notary protocol book. Leonardo’s grandfather, Ser Antonio da Vinci, had recorded them there, along with the births and baptisms of his own four children. The notebook was clearly of some significance to the family, as Leonardo’s great-grandfather, Ser Piero di Guido da Vinci, had previously owned it. He wrote: “There was born to me a grandson, the son of Ser Piero my son, on the 15th day of April, a Saturday, at the third hour of the night (10:30 p.m.). He bears the name Lionardo; he was baptized with the name Lionardo by the priest Piero di Bartolomeo da Vinci”.

The baptism of Leonardo in front of the family and ten witnesses suggests that despite his illegitimacy there was no attempt to conceal his arrival. Antonio’s note continues with the names of those witnesses. The parish priest in Vinci was Piero di Bartolomeo, a near neighbour of the da Vinci family home. Therefore, although the birth may have been in Anchiano, it is likely that the baptism took place in Santa Croce, the Vinci parish church. The font around which this event probably took place can still be seen, and is celebrated by a stone plaque on the wall of the small baptistery.

The Anchiano house stands on a promontory overlooking the Arno valley, with a view that finds reprise in Leonardo’s first known drawing (Fig. 1.1). Above the door of the house is the “da Vinci” family crest.1 It is known that Leonardo’s grandfather was involved in the sale of that house, as he is recorded as being called upon to draw up the sale contract in October of 1499.

Fig. 1.1

The house in Anchiano thought to be Leonardo’s first home

At that time, illegitimacy bestowed some penalties in education and potential social position, with limitations on access to some professions. For Leonardo, these limitations seem to have affected the breadth of his education, as later in life he records his struggle to learn Latin and Greek, but it seems that his illegitimacy did not stand in the way of a constructive childhood. It is very likely that his birth into a family of notaries and lawyers meant that he was nurtured in an environment of some scholastic significance; his beautifully neat handwriting with notarial flourishes attests to a significant degree of guidance and support in the basics of his education. Vasari reported that he was gifted in his abilities in mathematics, and his skills in geometry were certainly honed later through his association with Luca Pacioli. He was very well aware of the classics in his later years, as his own catalogue of his library attests. He is described as being a competent musician, performing with the lyre2 to a standard that brought him an appreciative audience.

The extent of the influence of his father in all of this is impossible to know. There is significant evidence to prove that Ser Piero no longer resided in Vinci at that time. Records show that in 1450, following a brief period in Pisa, he had already taken up a post as a notary in Florence. Therefore by that time Piero must have been a visitor to his home, perhaps drawn back by a beautiful girl with whom there could actually be no future. No more than 18 months after Leonardo’s birth, Piero married Albiera degli Amadori, the daughter of a wealthy Florentine notary. Being of higher birth, Albiera would have been much more in keeping with his intended station in life. It is important to note that following Leonardo, Ser Piero had no children by Albiera, who died in childbirth, and no further children until Leonardo was 20 years old.

It would appear that Leonardo grew up with his grandparents as guardians. In his 1457 tax return, Leonardo’s grandfather, Antonio, listed the 5-year-old Leonardo as being part of his household.3 His grandmother Lucia and his young uncle Francesco, with whom he had a lifelong relationship, were all together at that time. It is likely that Leonardo later spent a significant amount of time with his father in Florence, especially when apprenticed to the studio of Master Andrea del Verrocchio.

Meanwhile, his uncle Francesco remained childless and worked locally on the family properties around Vinci. Francesco owned a mill, and he and his brother Piero had rebuilt and managed a local kiln at the convent of San Pier Martire.4 His paternal grandmother had come from a family famous for their majolica pottery. Hence, Leonardo would have been exposed to artisan activities as well as being surrounded by olive groves and vineyards that are not much changed to the present day. As Leonardo’s uncle Francesco was closer in age to Leonardo than his brother Ser Piero, it is probable that he would have been a companion for Leonardo, as well as a substitute parent.

Leonardo’s father, Ser Piero, went on to have 4 wives and 11 legitimate children. It was perhaps fortunate for Leonardo’s emotional development that these stepsiblings all arrived after he had reached manhood and independence. When his father died, he left nothing to Leonardo, his first-born son. Yet when Francesco died, he left his entire estate to Leonardo. The result was a bitter feud between Leonardo and his stepsiblings.

One of the few facts known about Leonardo’s mother is that shortly after Leonardo was born, she married a local man, Antonio Buti, nicknamed “Acattabrigha” (the brawler). In local tax returns, Caterina is recorded as living with her family in Campo Zepo, close to Vinci. Caterina produced six children during the next 11 years, five girls and one boy. Her only legitimate son, Francesco, was killed by a shot from a military catapult.

Wherever Leonardo laid his head at night in those most formative of years, it seems clear that the family arrangements for the young Leonardo were not simple, and he must have experienced emotional tensions from many directions. Caterina’s growing family needed a lot of her attention, and Ser Piero’s busy life with a new wife in Florence kept them apart, Leonardo’s emotional and intellectual centre of gravity was probably with his grandfather, grandmother, and uncle. In his later notes, Leonardo refers to the funeral of a Caterina in an unemotional way.

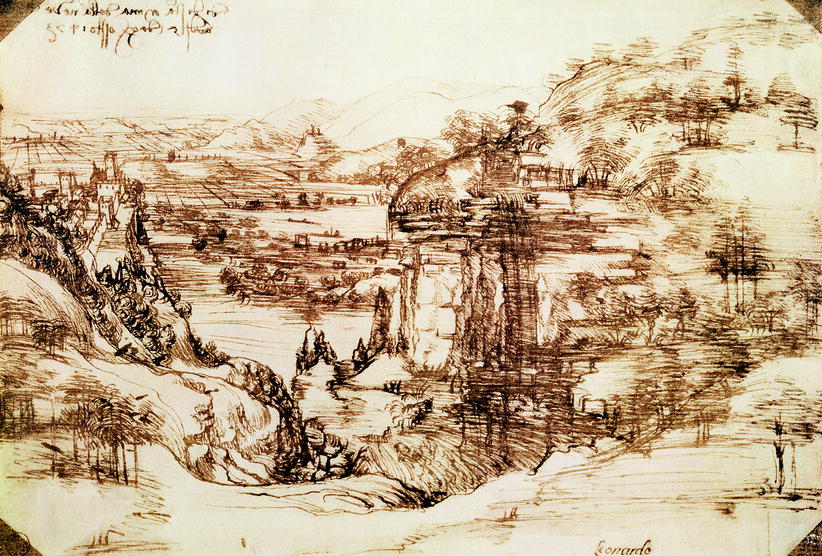

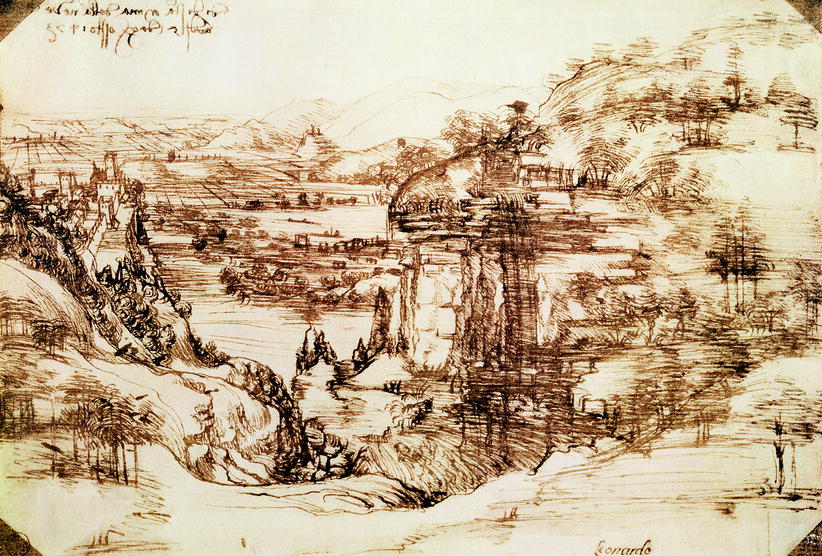

His keen observation of nature and his interest in the landscape can be seen in his earliest surviving known drawing (Fig. 1.2). This work by the young Leonardo can be dated quite precisely from the inscription upon it, written in his hand as 5 August 1473. The influence of his notary family can be seen in the flourish of his handwriting. At this time, he was 21 years of age and this was 1 year after his admission to the guild of painters in Florence. The beauty of the local countryside and the bustle of the small but strategically important regional town of Vinci would have had a very significant impact on the development of the young Leonardo. Certainly his interest in the natural world and man’s place within the macrocosm were to dominate his thinking throughout his life. Although this first landscape is more of a fantasia of his memory of home, there are identifiable landmarks. The contemporary landscape reveals features that are identifiable in the drawing (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.2

The first known drawing by Leonardo, depicting an imaginary landscape. ALG 152192. Arno Landscape, 5th August, 1473 (pen and ink on paper), Leonardo da Vinci/Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy/Alinari/The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig. 1.3

A small hill that seems to feature in Leonardo’s imaginary landscape

The enormous gifts of Leonardo are eulogized by Vasari in the first recognized reference text in art history, The Lives of the Great Artists and Sculptors.5 Among the many talents Vasari described, Leonardo was said to be a musician, “being gifted in music with a fine voice and a competent player of the Lira da Braccio,” but Vasari went on to give an impression of an inconstant Leonardo, who undermined his education with whimsical application, flitting from subject to subject (in which, despite his abbreviated attention, he often excelled). Vasari reported that soon after Leonardo started arithmetic, he could baffle his masters with his ability, but then he moved on to something else.

With regard to his artistic skills, Vasari reported that throughout his youth Leonardo never ceased to draw. Leonardo’s father recognized his son’s potential in the arts. Perhaps he saw in this skill an easy solution to a career for his illegitimate, capricious offspring. He introduced Leonardo to Andrea del Verrocchio, a friend and master of one of the most significant studios in Florence at that time.

The year 1464 was very difficult for Leonardo’s father. He had lost both his first wife and his own father. It would seem natural to want to move his son from Vinci into his household at that time. A common age for a young man to begin an apprenticeship was 14. It is not known exactly when Leonardo entered his apprenticeship but these traumatic events could have had some bearing on Ser Piero’s future plans for his son. At some time between 1464 and 1470, his father displayed some of Leonardo’s drawings to Master Verrocchio, leading to his acceptance as a pupil in this distinguished Botega. Verrochio was about 30 years old when Leonardo joined him, still a young man and not too dissimilar in age from Leonardo’s father. Verrochio’s studio was close to Ser Piero’s offices in Palazzo del Podestrè, opposite to the Bargello. In addition to musical and mathematical skills, Vasari attributed to Verrochio a very restless and enquiring mind. That being the case, he would have seemed an excellent tutor for Leonardo. It is likely that Leonardo’s father perceived him to be a good role model for his son. In Verrocchio’s studio, Leonardo was surrounded by much of the greatest artistic talent of the day in Florence. Some of Leonardo’s fellow pupils included Perugino, Lorenzo de Credi, and Ghirlandaio. The apprenticeship served by Leonardo in such a high-profile and prolific workshop must have fanned the flames of his creativity, but perhaps also fed into his capricious nature. We can find examples in his notebooks. On the cover of manuscript F (Paris), he wrote a stream of unrelated questions that were clearly in his mind at the same time: “inflate the lungs of a pig. Avicenna on fluids. Map of Elefan of India, which Antonello Merciaio has. Enquire at the stationers for vetruvius. Ask Maestro Mafeo why the Adige rises for 7 years and falls for 7 years. Go every Saturday to the hot baths and you will see naked men”.

The artist’s studio of those days was called a “bottega,” a workshop or workplace. As the word implies, this was no simple studio designed only for painting or sculpture. These were places of great endeavour open to commissions in many disciplines. The work of the bottega would have ranged from engineering and architecture to the fine arts. Although the inventory of Verrochio’s studio’s skills was complete, he was best known as a goldsmith and a sculptor. He was described by Vasari as a wooden painter, gifted in effort and application rather than having innate talent. An example of his work, the Baptism of Christ, can be seen in the National Gallery in London. Although ascribed to the head of the studio, often many hands were involved in a commission such as this. Indeed, the studio method of the day meant that the production of such a painting would be a team effort by the master and his pupils.

A product of Verrocchio’s studio, utilizing the dual skills of engineer and metal worker and still visible today, is the gilded copper orb that sits on the top of the lantern of Brunelleschi’s dome of the cathedral in Florence. This was completed by May 1471 (Fig. 1.4). Leonardo witnessed its construction and may indeed have had a hand in it. He referred to it years later in Paris manuscript G (G.84v), written in 1515, whilst in Rome.

Fig. 1.4

The gilded orb atop Brunelleschi’s dome of the cathedral in Florence

Other than putative portraits of Leonardo as an aged man, there are no definitely attributable images of him. As a young man, he was described as strikingly good looking and graceful, with great intelligence that charmed all who came in contact with him. Vasari wrote that “He was a man of outstanding beauty and infinite grace. He was striking and handsome and his great presence brought comfort to the most troubled soul.” Vasari went on to say that “he owned nothing…and worked very little, yet he always kept servants and horses.” The Anonimo Gaddiano said of him that “He was very attractive, well-proportioned, graceful and good looking,” with beautiful hair, arranged in ringlets “down to the middle of his chest.” He was said to have dressed flamboyantly, and one reference describes him in a pink tunic. He was reportedly exceptionally strong, and Vasari said that he had been seen to bend an iron horseshoe with his bare hands. How much of this is true is not known, but the mythology is so strong and reported from so many different sources that some of it is likely to be true. Perhaps Leonardo’s youthful appearance can be guessed at through a possible likeness captured by his master Verrocchio in his beautiful bronze sculpture of David (now held in the Bargello in Florence) and a possible self-portrait to the right-hand side of the unfinished Adoration of the Magi owned by the Uffizzi gallery, also in Florence (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

(a) Verrocchio’s David. BEN 93596. David, c.1470 (bronze) (see also 220043), Verrocchio, Andrea del (1435–88)/Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library. (b) Detail from The Adoration. BAL 33484. The Adoration of the Magi, 1481–2 (oil on panel), Leonardo da Vinci/Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library

The image of an athletic, graceful youth with long hair in ringlets is realised in several images in Leonardo’s notebooks. Whether all of these are merely stereotypes of physiognomy that Leonardo found attractive or whether they are more personal is interesting to speculate. He certainly cultivated an impression of poise and individuality. His description of the refinement of his profession is well drawn in this quotation by Leonardo: “The painter sits in front of his work at perfect ease. He is well dressed and wields a very light brush dipped in delicate colour. He adorns himself with the clothes he fancies; his home is clean and filled with delightful pictures and he is often accompanied by music or by the reading of various beautiful works”6 All surviving biographies from the time testify to his aura of gracious brilliance.7

The studio system of the time relied upon commissions of many kinds, especially religious paintings. Alongside the hand of the master, these often had the hand of some of the apprentices as they matured in their skills. Perhaps the earliest extant example of Leonardo’s hand with the paint brush can be seen in the little dog at the bottom of the painting entitled Tobias and the Angel.

The maturation of Leonardo as an artist is revealed in a story recounted by Vasari, who suggested that in one such project, a painting of the baptism of Christ (1473–1476), Verrocchio was so overwhelmed by Leonardo’s rendering of the head of the angel at the left side of the picture that he was moved to put down his brush and not to paint again, in deference to Leonardo’s superior skill.

In 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo was admitted to the Florentine confraternity of painters, the Company of St. Luke, which also included the doctors. This signaled the end of his apprenticeship and the beginning of his career as an independent artist. His relationship with his now ex-master, Verrocchio, was clearly a strong one: Despite completing his apprenticeship, he is registered as part of Verrochio’s household in 1476.

During Leonardo’s apprenticeship and throughout his early years in Florence as a full-fledged artist, the titular head of the Florentine republic was Lorenzo de Medici. He held this position through the power and financial interests of the Medici family. An intelligent, well educated, and articulate man of significant physical stature, Lorenzo must have been an impressive personality to the young Leonardo. During the period of 1475–1482, the Anonimo Gaddiano suggested that Leonardo enjoyed the patronage of Lorenzo de Medici, at times working and studying in his famed sculpture garden, later frequented by Michelangelo. Although little other than the Anonimo’s report remains in the historical record to link Leonardo to Lorenzo with any intimacy, they may have had some kind of relationship. Born in 1449, Lorenzo was of similar age to Leonardo. He rose to prominence during Leonardo’s formative years in Florence. Both Leonardo’s father and his master Verrocchio were likely to have had contacts with the Medici household. Ser Piero would provide legal and notarial services for the Medici, and Verrocchio carried out commissions for them, some of which Leonardo was likely to have had a hand in. Interestingly Vasari does not mention Lorenzo in context with Leonardo.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree