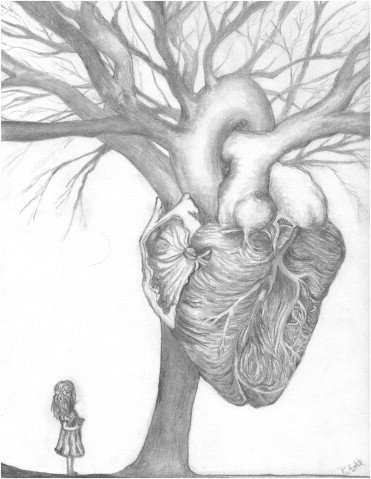

Art, literature, and imagination enhance our practice of medicine and enrich our professional world with deeper texture and more complex meaning. The charcoal pencil sketch of the Heart and Vascular Tree ( Figure 1 ) was a spontaneous gift from my 16-year-old daughter, Emily. The arborization of the heart and vascular system can be easily conceptualized using the tree as a metaphor. We typically describe the cine angiogram of the normal pulmonary artery as “normal arborization”; and this metaphor is quite appropriate because the vasculature contained within the lung looks very much like a mature healthy tree. Metaphors can however be conflicting. When we prune a tree, our intention is to stimulate healthy growth and arborization of the canopy. Conversely, pruning of the pulmonary vasculature seen on an angiogram signifies the unhealthy proliferative changes of pulmonary hypertension, which is a most serious disease. In Emily’s sketch, the little girl is likely looking up in wonder and reconciling the eerie and scary growth of the heart with the more flowing branches of the aorta and pulmonary artery merging into the more comfortable and familiar boughs of an old oak tree.

The sketch was cultivated in her imagination and fertilized by her observations of the oak trees that are common in the Ragged Mountains of central Virginia where we live and by her awareness of my long career in cardiology and my love of the natural world. She made another enchanted connection with this sketch. During a short stay as a student at the University of Virginia during her first year in session in 1826, Edgar Allan Poe often wandered into the forests of the Ragged Mountains that lie south and west of Charlottesville. He wrote one short tale about this experience: A Tale of the Ragged Mountains . On reading this tale, it became apparent to me that the meticulous description of the primary character Augustus Bedloe was an astute depiction of the phenotype of the most well-known syndrome that affects the heart and vascular system—the Marfan syndrome. Poe’s description of Bedloe observes,

But in no regard was he more peculiar than in his personal appearance. He was singularly tall and thin. He stooped much. His limbs were long and emaciated. His forehead was broad and low. His complexion was absolutely bloodless … his teeth were more wildly uneven than I have ever before seen in a human head.

This depiction by Poe occurred >50 years before the classic case described by Professor Antoine Marfan in Paris in 1896 and surely resonates with any who have cared for patients with the Marfan syndrome and appreciate the consequences of long bone overgrowth (dolichostenomelia) and the translucent appearance the skin can assume. The most profound phenotypic expression of the Marfan syndrome in my practice is present in a young man currently living in Charlottesville and the high arching of his palate has created dental crowding to a degree where “his teeth were more wildly uneven than I have ever before seen in a human head.” More than once I have contemplated that Poe’s description of Bedloe was patterned after someone in Charlottesville with the Marfan syndrome that he actually knew and that my patient is a distant descendant of that fellow with similar penetrance of that selfsame genetic mutation. Emily’s pencil sketch makes a magical connection and mosaic of literature, medicine, imagination, and the world of trees. Could it be that Poe’s telltale heart escaped from beneath the floorboards and climbed up into this stately oak transforming it into the telltale tree? To answer that question, one might need to summon the ancient Druid poets of Wales; the word Druid is derived from the Welch word “derwydd,” which means oak-seer. For centuries, trees have been at the center of the poetic imagination and Druid colleges were situated within forests and groves. In Celtic languages, “trees” literally means “letters” and “beech” (tree) is synonymous with “literature” and “book” in many languages.

My early career developed in northern Vermont where I initially became acquainted with the Marfan syndrome and where I developed a fascination with the forests and trees of New England. Those same forests and trees were an arboretum for the imagination of America’s great lyric poet, Robert Frost. Frost’s poems are full of maples, beeches, hemlocks, birches, oaks, and apple trees. Frost’s trees become metaphors between poet and reader and allow the expression and understanding of things from the simple to the sublime. Depicting the mundane task of acquiring wood for heat in “In Winter in the Woods …” Frost forages,

In winter in the woods alone Against the trees I go. I mark a maple of my own And lay the maple low.

The question asked in On a Tree Fallen Across the Road becomes slightly more complex and spiritual.

The tree a tempest with a crash of wood Throws down in front of us is not to bar Our passage to our journey’s end for good, But just to ask us who we think we are Insisting always on our way so.

Those familiar with New England are captivated by the imagery in “birches” and the site of those trees bent by wind and weighted down with ice is magically captured by Frost who prefers to think the birches were bent by someone swinging on them. The “swinger of birches” is oscillating downward toward earth and upward “Toward heaven, til the tree could bear no more.” The tree as a portal to a more ethereal place is a motif for Frost and recurs in After Apple Picking ,

My long two-pointed ladder’s sticking through a tree Toward heaven still, And there is a barrel that I didn’t fill Beside it, and there may be two or three Apples I didn’t pick upon some bough. But I am done with apple picking now

In this passage, the admixture of his tired terrestrial being with the ladder pointing toward heaven is a wonderful metaphor of opposites. I remember a very difficult day grieving the death of a dearly beloved patient whose life I had the privilege of sharing for years. In the cold winter evening, I went for a walk in the Vermont woods to contemplate these events, and while passing beneath an old hemlock, a surprised bird departed a bough and showered snow down my coat that was cold against my skin startling me. To the poet, this event is not an irritating inconvenience, rather it is an opportunity to see it differently as expressed by Frost in Dust of Snow ,

The way a crow Shook down on me The dust of snow From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart A change of mood And saved some part Of a day I had rued

This is the complex skein of our existence: moments of sadness and mourning punctuated by a small event in nature that can be so poetic that it is transformative “and that has made all the difference” ( The Road Not Taken , Robert Frost). As I marvel at Emily’s sketch, I am reminded of exiting those woods that day in Vermont with my sadness somewhat reconciled by a subtle sense of joy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree