7

The ECG in Patients with Palpitations or Syncope

‘Palpitations’ means different things to different people, but essentially it means an awareness of the heartbeat. ‘Syncope’ means sudden loss of consciousness. The only way of being certain that a cardiac problem is the cause of either phenomenon is to record an ECG when the patient is having a typical attack, but this is seldom possible. Nevertheless, the ECG can be helpful, even when the patient is well.

THE ECG WHEN THE PATIENT HAS NO SYMPTOMS

If a patient is well at the time of recording, four possible ECG patterns can point to a diagnosis:

NORMAL ECGs

Symptoms may not be due to heart disease – the patient may have epilepsy or some other condition. However, a normal ECG does not rule out a paroxysmal arrhythmia, and the patient′s description of his or her symptoms may be crucial. For example, if the patient′s attacks are associated with exercise (think of anaemia) or anxiety, and the palpitations build up and slow down, sinus tachycardia is likely to be the cause of the symptoms. In paroxysmal tachycardia, the attack begins suddenly, often for no obvious reason, and may stop suddenly. Ambulatory recording over 24 h, using, for example, the Holter technique, may be necessary to obtain a record of an attack ( Fig. 7.1).

PATTERNS SUGGESTING CARDIAC DISEASE

Marked T wave inversion may suggest either left ventricular hypertrophy or left bundle branch block, which may be due to aortic stenosis; or right ventricular hypertrophy, which may be due to pulmonary hypertension. In a young person, who is unlikely to have coronary disease, this pattern pattern suggests hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ( Fig. 7.2), which is associated with arrhythmias, syncope and sudden death.

PATTERNS SUGGESTING PAROXYSMAL TACHYCARDIA

Pre-excitation syndromes

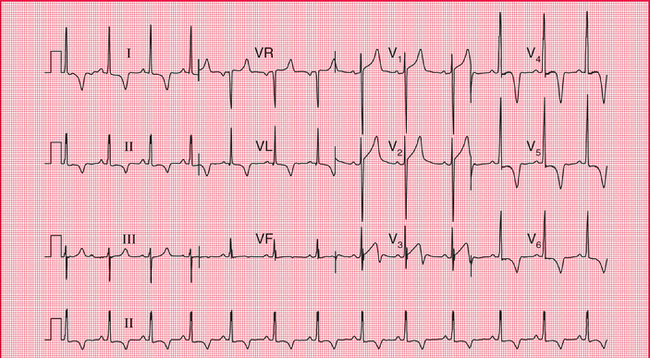

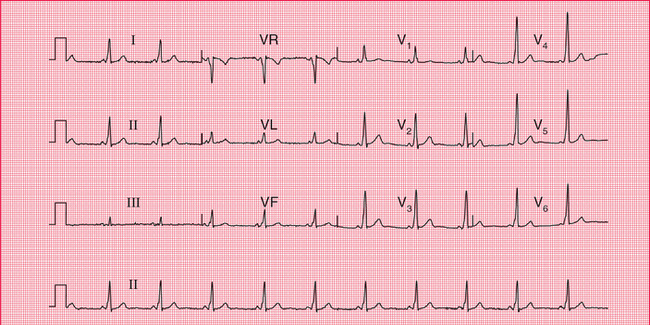

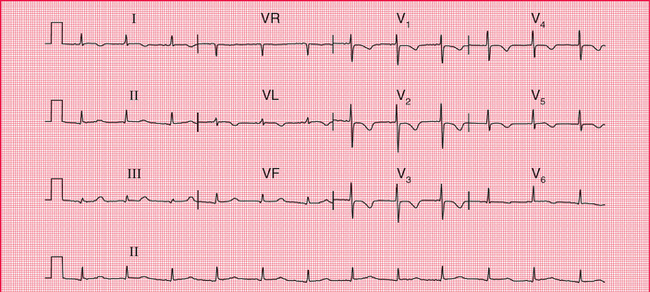

In the WPW syndrome, the abnormal pathway connects the atrium and the ventricle, and the QRS complex is wide, with a slurred upstroke. In the WPW syndrome type A, the pathway is left-sided, connecting the left atrium and left ventricle, and causes a dominant R wave in lead V1 ( Fig. 7.3; for another example see Fig. 3.28). This may be confused with right ventricular hypertrophy. Less commonly, the abnormal pathway can be right-sided, connecting the right atrium and right ventricle, and this is called the WPW syndrome type B ( Fig. 7.4). Here, lead V1 has no dominant R wave but has a deep S wave, and there is anterior T wave inversion, which may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of anterior ischaemia. The wide QRS complex seen in both types of the WPW syndrome may also lead to a mistaken diagnosis of bundle branch block, although the characteristic ‘M’ pattern of the QRS complexes in left bundle branch block is not seen in the WPW syndrome.

Fig. 7.4 The Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome type B

Note

• Sinus rhythm, rate 55/min – P waves best seen in lead V1

• The first complex is probably a ventricular extrasystole

• Broad QRS complexes (160 ms) with a slurred upstroke (delta wave), seen best in leads V2–V4

• Inverted T waves in leads I, II and VL, and biphasic T waves in leads V5–V6

• The small second and third complexes in lead II appear to be due to a technical error

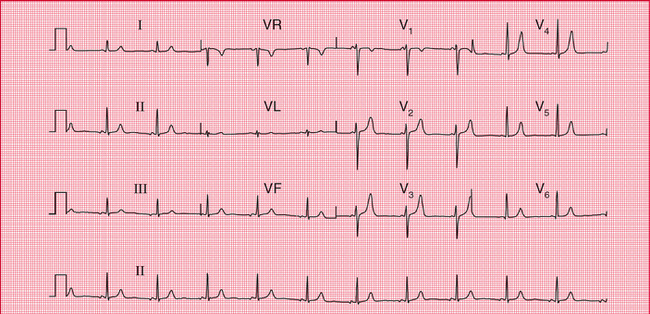

In the LGL syndrome the abnormal pathway connects the atria to the His bundle, so there is a short PR interval but a normal QRS complex ( Fig. 7.5).

Long QT interval

The QT interval varies with the heart rate (and also with gender and the time of day). The corrected interval (QTc) can be calculated using Bazett′s formula:

A QTc interval longer than 450 ms is likely to be abnormal. QT interval prolongation can be congenital, but is most often due to drugs, particularly to antiarrhythmic drugs ( Box 7.1 and Fig. 7.6).

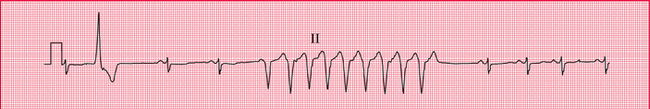

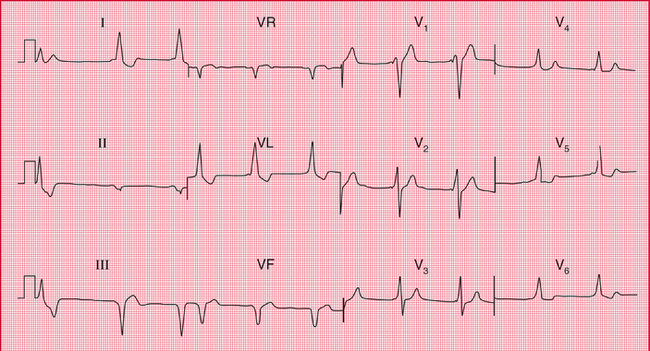

Whatever its cause, a corrected QT interval of 500 ms or longer can predispose to paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia of a particular type called ‘torsade de pointes’, which can cause either symptoms typical of paroxysmal tachycardia or sudden death. Figure 7.7 shows a continuous ECG from a patient who was being treated with an antiarrhythmic drug and who developed ventricular fibrillation while being monitored. A few seconds before the cardiac arrest, he developed a transient broad complex tachycardia in which the QRS complexes were initially upright but then changed, to become downward-pointing. This is typical of ‘torsade de pointes’ ventricular tachycardia.

Fig. 7.7 Torsade de pointes ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation

Note

• The three rhythm strips are a continuous record

• The underlying rhythm is sinus, rate about 100/min

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree