The Decision-Making Process in Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Lutz Prechelt

Peter Lanzer

Introduction

As the range and quality of endovascular instruments improve, the industry supplying these tools is increasingly trying to create the impression that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a simple and straightforward procedure. It is nothing of the sort. In PCI, in fact, an operator performs high-risk procedures under time pressure, with only indirect and incomplete angiographic information about the interventional site, and is constantly trading off one risk against another. Mastering this complex process requires years of experience and an attitude characterized by the constant willingness to learn and reflect when faced with each unexpected development or new situation. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, the complexity of this repetitive and evolving process, consisting of the triad of angiographic imaging, image interpretation, and interventional action, has not yet been fully described. Furthermore, there are no data on the factors determining the decision trade-offs or their relative weights in various common situations. Consequently, physicians learning PCI today need a gifted teacher or have to gain experience the hard way, by trial and error, which exposes patients to avoidable risks and complications. Existing materials on learning PCI (e.g., references 1,2,3,4) describe only formal training requirements and the parameters of institutional and operator competence. They provide no help on how to make hard decisions during an intervention.

The purpose of this chapter is to start filling this void by providing an overview of some important basic factors and how they interact. One obviously cannot fully describe the actual decision-making process because, although each component of the triad and the resulting trade-offs are quantitative in principle, most of these quantities cannot be measured in practice. Therefore, only general decision-making rules can be formulated to facilitate the training and clinical experience necessary for becoming a master PCI operator. We hope that this description will help transform a rather vaguely formulated practical exercise into a conscious process of skill acquisition. The goal is to become capable of successfully handling even unexpected and adverse developments in the course of complex interventions.

The following section describes the basic elements of the PCI decision-making process, whereas the process itself is described in subsequent sections. We assume that the reader has a basic understanding of the PCI process and that the elements therefore need little or no description.

Input and Output Variables

The PCI decision-making process involves a number of input and output variables. The input variables include:

Interventional scenario

Emergency or elective

General patient status

General health

Cardiac function

Cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., type II diabetes)

History of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., coronary bypass surgery)

Stability (clinical, hemodynamic, electrical)

Current physician status

Rested or exhausted

Skilled in handling unexpected developments or overwhelmed by them

Stress resistant or low in morale

Accumulated time and costs

Procedure time

Radiation exposure

Contrast agent dose

Monetary costs (physician, staff, equipment, material)

Schedule pressure (availability of physician, staff, and laboratory)

Current interventional status

Presence of single/multiple lesions

Presence of single/multiple coronary artery diseases

Presence of stents or coronary bypasses

Target vessel size and status

Location, severity, and complexity of the target lesion

Status of the antegrade coronary blood flow

Amount of dependent myocardium

Availability of required instrumentation

Status of deployed instrumentation

Guiding catheter

Guidewire

Balloon catheter

Stent

Pressure/volume sensor

Ultrasonic sensor

Performance of deployed instrumentation

As expected

Suboptimum

Malfunctioning

Tracking, crossing, pushing abilities

Uncertainty about the reliability of all of the above information

The output variables in PCI decision making, that is, the potential actions of the operator, include:

Initial actions

Establishing arterial access

Placement of the guiding catheter

Imaging

Image acquisition (cine, fluoroscopy) and visualization of the target vessel and lesion

Imaging by ultrasonic sensor

Review and interpretation of acquired images

Initial and subsequent interventions

Placement of the guidewire

Placement and inflation of the balloon catheter

Stent deployment

Employment of auxiliary techniques (whether diagnostic or revascularization)

Removal of equipment and instrumentation

Auxiliary acts

Drug administration

Addressing and responding to staff

Addressing and responding to the patient

Termination of the procedure

Risks and Benefits

The primary categories used to judge the consequences of each subsequent interventional step are those of benefit and risk. Benefits are what we would like and expect to achieve in both tactical and strategic terms, whereas risks we would rather avoid, but can never be sure of doing so. The benefits we strive for include remedy or palliation of the coronary artery syndrome and an improved prognosis, or at least preparing the ground for later definitive repair. Since most risks and risk considerations are inherent in the PCI procedure itself, they play a prominent part in the entire decision-making process. They are discussed in the following section.

Risk Considerations

The central consideration in the decision-making process during PCI is risk and how to prevent, evaluate, and control it. A thorough understanding of the character and magnitude of the risks and benefits involved in each interventional step is crucial for effective decision making during a PCI.

Risk can be defined qualitatively or quantitatively. Qualitatively, a risk is just any undesirable event that may or may not occur. If it occurs, the risk is said to materialize. Quantitatively, risk is the product of the probability of the event and the damage expected if it happens. Here, we are interested in the quantitative understanding of risk: Risk is the extent of damage expected in terms of its probability. It is important to note that we may use this notion of risk even if we understand the probability and the size of the damage only vaguely (high uncertainty). In the context of PCI, we clearly cannot express risk as a number, but the notion will still help to distinguish greater risks from lesser ones.

The task of a PCI operator is to identify the course of action with the lowest overall risk and highest benefit for the individual patient.

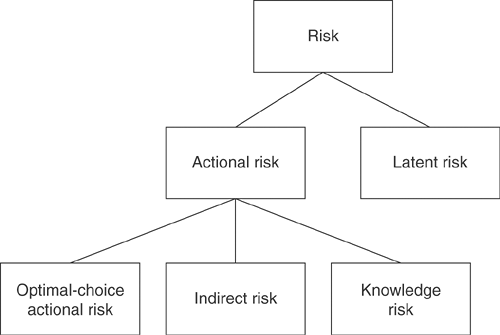

We distinguish between two very different kinds of risk, namely, latent and actional risk, and two different ways of dealing with each of them. Actional risk is further subdivided to reflect a possible adverse course of PCI (see Fig. 4-1).

Latent Risk

Latent risk is risk that is already inherent in the individual situation before any procedure is initiated and which remains there unless removed. The most typical example of latent risk in the context of PCI is myocardial infarction. Latent risk may materialize at any time or, at least in elective cases, it may remain dormant.

There are two ways of dealing with latent risk: One may either accept it and not address it, or mitigate it by working actively to reduce it.

The two main purposes of PCI are mitigation of the latent risk and reduction of a patient’s symptoms.

Actional Risk

Actional risk is that risk created by the actions of the operator, whether diagnostic or interventional. PCI involves many different actional risks including vessel closure, dissection and perforation of the target vessel at the target lesion, and vessel wall damage elsewhere in the coronary circulation or along the vascular access path, with ensuing local and/or systemic complications and patient instability.

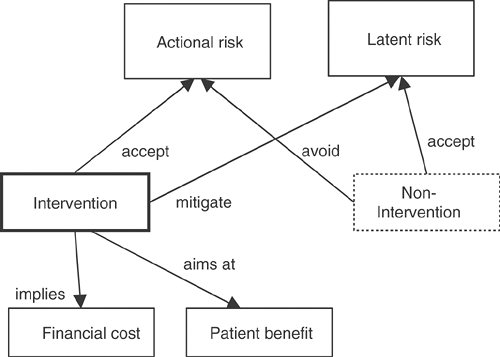

There are two ways of dealing with actional risk (see Fig. 4-2): One may either avoid it by not performing the respective action, or accept it and perform the action anyway.

The main issue for PCI is to identify those actions that, given the context of the current procedure, result in the maximum reduction of latent risk with a minimum and acceptable level of actional risk. Much of PCI decision making revolves around the question of what constitutes acceptable actional risk.

In terms of risk management, there is a great difference between emergency and elective PCI. During emergency PCI, the operator will be prepared to accept substantially higher levels of actional risk for two reasons. First, in patients with acute coronary syndromes and hence the high latent risk of permanent myocardial damage or cardiovascular death, there is a lot to be gained by taking higher actional risks. Second, the need for rapid action conflicts with the lengthy evaluation of risk factors and the consequent risk reduction that might be possible in elective situations.

FIGURE 4-2. Relationship of intervention (vs. nonintervention) to the risk types actional risk and latent risk. |

Actional risk is always accompanied by two other effects. First, the intervention entails concrete financial costs, which rise with its duration, the number of steps involved, and the materials required. Second, if successful, the intervention will result in some kind of benefit. This benefit, whether a reduction of latent risk or merely the preparation of such a reduction, must be traded off against both actional risk and costs. Furthermore, when looking at the actual PCI decision-making process, it is useful to consider the three additive components of actional risk: optimum-choice actional risk, knowledge risk, and indirect risk.

Optimum-choice Actional Risk

Optimum-choice actional risk refers to that part of actional risk that an ideal operator acting under ideal circumstances would accept, in particular, given perfect information about the current status of the vessels. Optimum-choice actional risk is the actional risk incurred by those interventional steps that are required for optimum success.

Knowledge Risk

Knowledge risk is the part of actional risk incurred only because the operator’s information about the vessel and lesion status is incomplete and imprecise (see Chapter 3B for the shortcomings of x-ray coronary angiography in visualizing the interventional site). Incomplete information or incorrect image interpretation may start a chain of inaccurate judgments, possibly leading to a suboptimal or overly dangerous intervention, and which in turn leads to increased actional risk. This increase in actional risk we call knowledge risk. There are three ways to reduce knowledge risk: first, by means of optimized image acquisition and evaluation; second, by performing additional diagnostic evaluations such as flow/pressure measurements or intracoronary ultrasonography; and third, by obtaining tactile information if the operator demonstrates advanced manual dexterity and operational skills. Note that extending diagnostic evaluations will always imply actional risk and must be traded off against the reduction in knowledge risk.

Indirect Risk

Indirect risk refers to the part of actional risk incurred by voluntarily giving up existing benefits. This is best explained by an example: Assume we have a guiding catheter in place in a vessel. If the PCI is not yet terminated, this is a benefit. Now, assume we want to exchange this catheter for another one (say, to switch from 5F to 7F). Obviously, this step involves actional risk since we may inflict damage on the patient during catheter exchange. However, even if no damage occurs, it may happen that for some reason the target vessel cannot be accessed because it proves impossible to appropriately position either this new catheter or any other one tried later. Thus, by removing a guiding catheter, we risk losing the benefit of having a well-positioned catheter (even if only 5F) in place. The possibility that this will happen is represented as indirect risk.

The only way to reduce indirect risk is by carefully planning the potential courses of intervention that may lie ahead, and how to proceed without giving up any intermediate benefits.

Indirect risk can often be reduced at the expense of financial cost by using the equipment best suited for a job rather than the cheapest that is expected to be sufficient.

Risk Level Classification

To roughly classify the level of risks, we propose a five-level ordinal scale with the levels very low, low, medium, high, and very high. The component aspects probability of the adverse event and expected resulting damage can be described on the same scale. In principle, it is possible to describe the meaning of the probability levels numerically as a percentage. However, as people are known to estimate probabilities poorly, this is unwise. In any case, no intersubjective scale is available to quantitatively represent the damage incurred. Overall, the classification of both probability and damage (and thus of the total risk) is subjective and difficult. Therefore, a significant aspect of the skill of a master PCI operator consists in the ability to accurately (if not precisely) assess and compare the levels of alternative risks.

It is important to understand that potentially all aspects of PCI entail actional risk, even such apparently innocent acts as considering a decision (because that takes time during which the patient may become unstable) or terminating the procedure by suturing the access site (because that involves removal of the sheath and wound closure, and hence lack of an emergency access in the case of acute complications). Nevertheless, some actions carry an obviously greater risk than others. The most risk-intensive actions during PCI are usually the following:

Using force in advancing instrumentation

Inflating a dilatation balloon at high pressures (with or without a stent)

Inflating an oversized dilatation balloon at any level of pressure (with or without a stent)

Recanalization of subacutely occluded vessels

Crossing subtotal occlusions

Recrossing iatrogenically unstable lesions, iatrogenic coronary artery occlusions, and incomplete stent apposition

For all of these, the actional risk is high because of the large knowledge risk component involved. Knowledge risk is high for several reasons:

The information available about the status of the interventional site based on x-ray angiography is incomplete and imprecise.

The ensuing damage when an injury is inflicted is usually severe.

Access to the vessel may be compromised, making further deployment of instrumentation dangerous or impossible.

Value of Operator Experience

The difficulty with minimizing risk during a PCI is obviously the fact that the risk inherent in any situation or step is usually uncertain and can only be estimated. Much of the experience of a master PCI operator is reflected in the precision and accuracy of his or her risk estimates and also the ability to manage unexpected and adverse outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree