Chapter 6

The construct of breathlessness

Sara Booth1 and Robert Lansing2

1Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK. 2Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Correspondence: Sara Booth, Box 63, Elsworth House, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2OO, UK. E-mail: sb628@cam.ac.uk

We will discuss the “construct for breathlessness” in its broadest sense to reflect the fact that breathlessness is a symptom indirectly measured and highly dependent upon a complex combination of physical sensations, thoughts, perceptions, cultural conditioning and emotional states. We will consider our progress in obtaining a common scientific understanding as well as developing a working “construct” in its clinical management. Definitions and descriptions of breathlessness have focused mostly on how clinicians and scientists understand this symptom to the neglect of formulations directly related to the implementation of clinical management and relief. We consider the need to relate the language and findings of clinical and laboratory research to the patient’s need to understand and respond to their own experience of breathlessness. To this end, we will consider the diversity and evolving concepts of the nature of the symptom in the scientific community and the practicalities of applying these to patients, particularly those faced with a lifetime of suffering.

Julius Comroe, the eminent cardiologist, showed great prescience when he stated that breathlessness “involves both the perception of the sensation by the patient and his reaction to it…” [1]. This insight remains the foundation of the current clinical management of chronic, refractory breathlessness in advanced disease. It may even be called a “construct of breathlessness”.

It is now more usual to express this original construct as the importance of managing both the perceptual and affective dimensions of the symptom. Paying attention to these aspects of care is recognised as crucial in reducing the impact of breathlessness, thus improving the quality of life not only of those who suffer from breathlessness but also of those closest to them. The lives of those close to someone affected by breathlessness are also profoundly constrained, both emotionally and physically, by the symptom. Breathlessness is now recognised as a complex experience of the mind and body [2], with wide-ranging, damaging effects on everyone connected to the person living with it.

When Comroe defined breathlessness, he was speaking at the first symposium on the symptom in 1965 [1]. This was convened with the purpose of bringing together general medical clinicians and scientists to improve understanding of this disabling, often invisible, symptom [3]. Although it quickly focused on pathophysiology, this landmark meeting laid a foundation for the progress that has been made in the last 50 years in understanding not only the causes but also the consequences of this devastating symptom. It also represented recognition that the effective investigation and management of breathlessness required clinicians and scientists from a range of disciplines and backgrounds to work together.

Palliative care was not a specialty at this time. Healthcare systems did not recognise the need to care actively for people who were dying or had symptomatic advanced disease. Cicely Saunders was the pioneer in this field and had been working to develop her ideas into a coherent philosophy that could be translated into clinical care. Effective symptom control was at its heart, and the first modern hospice, St Christopher’s in south London, UK, opened in 1967, 2 years after the breathlessness symposium [4, 5]. It became a place where research into symptom control was supported: one of the first clinical trials in the management of breathlessness was carried out there, led by Abe Guz, who had been at that first meeting [6].

Much of the work recognising the immensely distressing impact of breathlessness has been carried out in palliative care. Increasingly, however, “advanced disease clinics”, encompassing symptom relief, are being set up in departments of respiratory medicine and cardiology (N. Smallwood, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia; personal communication). Recently, statements from the heart of academic respiratory medicine have called for palliative care to be provided for patients with respiratory disease [7], and for breathlessness to be named the “first vital symptom” that should be measured in every patient [8, 9]. It seems to us that this is a propitious time to review the breadth and depth of the applications of Comroe’s construct, and to understand any need for its further development to make it useful to those with an interest in shortness of breath, particularly patients and families.

It is clear to us that any useful construct of breathlessness must resonate with clinicians and scientists in the ward, clinic and laboratory, and with those engaged in psychosocial research; in other words, it must have “face validity”. We have interpreted this brief quite widely using historical as well as contemporary ideas of breathlessness, highlighting areas that we consider need further examination, without reviewing them fully. The complex effects of breathlessness, its assessment, general management, the personal experience of living with it and other related areas, are well described and are reviewed in detail elsewhere in this issue of the Monograph.

A useful construct should synthesise the latest research and best historical thinking on this subject. We name under-researched aspects of breathlessness that offer opportunities to make significant contributions to our understanding and management of the symptom. We will discuss the diversity and range of the construct’s many possible applications and the special difficulties in relating ideas and findings from different fields, particularly between scientific research and clinical care.

Comroe’s early insight remains critically important: that the way an individual patient reacts to his or her experience of breathlessness is central to its severity. We would now understand that this reaction can be modified. Help is often necessary, using approaches that stem from a growing understanding of the genesis of breathlessness and the evidence accumulating in the arts and sciences of central nervous system functioning, psychology, the humanities and physical activity.

Diversity of application

The most widely accepted current definition of pathological breathlessness defines it as “A subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity. The experience derives from interactions among multiple physiologic, psychological, social and environmental factors and may induce secondary physiological and behavioural responses” [10]. This has served the science of breathlessness well but cannot, and was not intended to, form a construct of breathlessness that meets patients’ and families’ needs for greater understanding of the symptom. It may also be of limited application in the fields of philosophy and the other humanities [11]; it does not consider life before breathlessness.

Patients often seek help outside mainstream medicine, as they may receive little support with managing this all-encompassing symptom. Any construct would ideally be comprehensible in all spheres of society so that everyone can understand the difficulties of living with chronic breathlessness, a symptom without the social notoriety of pain. Greater general understanding of breathlessness could reduce the social isolation and guilt that many with the symptom experience. It is not uncommon for patients, particularly smokers, to demonstrate a feeling of being unworthy or undeserving of help, feeling that they have brought the symptom on themselves.

Health service managers have a profound impact on the likelihood of effective management of the breathless patient, so the construct needs to speak to this constituency too. We therefore hope that any general construct can be of use to people from any background who live with the symptom, or who wish to investigate it or help others manage it.

A general construct of breathlessness used by investigators and clinicians in their many separate fields can provide both a shared language and methodologies of assessing breathlessness. It will facilitate the integration of information and promote the cross-fertilisation of ideas developed in various specialties, both of which are aspirations of the American Thoracic Society statement [10] and the original symposium [1]. A continuing challenge is to relate the findings and ideas developed in special fields, for example those obtained with healthy subjects in the special conditions of the laboratory with those obtained from patients in clinical settings. In what ways are these similar or different? Is breathlessness from chest strapping in the laboratory a good model of breathlessness in restrictive lung disease [12, 13]?

It is important to recognise the limitations of our current construct and to view it as still evolving. It must be able to accommodate corrections and incorporate new findings and ideas. Variations and modifications will emerge from the special requirements of these separate fields: different populations, experimental manipulations, ways of measuring breathlessness and new theoretical approaches. New or apparently novel ideas and findings, given time to develop, could be of value and later incorporated into a general construct.

Assessing breathlessness by the patient’s report: the sine qua non of the construct of breathlessness

Descriptions

For too long, patients’ reports of breathlessness were unheard or overlooked [14], possibly because clinicians’ uncertainties about how to treat the symptom discouraged them from eliciting it or “noticing” it in patients’ stories. Unlike pain, breathlessness has not been frequently and consistently assessed, in spite of evidence that it is a better predictor of clinical outcomes than other parameters [15]. It seems to us that the patients’ reports of the private experience of breathing discomfort are the core of any breathlessness construct. As their reports are available to us primarily through language (conversations, interviews and questionnaires), our present construct has developed largely through a better understanding of the words and expressions used to describe it. Inferring breathlessness from observation of breathing behaviour is now being studied [16, 17] but still requires verbal reports for validation.

The transition from simple terms, such as “breathlessness” and “shortness of breath”, to our present understanding of the several dimensions of the experience has largely been through the systematic study of patients’ own words in relation to physiological and clinical states, using sophisticated statistical methods to analyse their frequency and grouping [18–21]. These studies have shown a remarkable similarity in their use among diverse groups and populations, in spite of cultural and individual differences, and form the basis of our conversation with subjects, as well as our professional interactions. Chest tightness, air hunger and increased work of breathing (or their synonyms) have emerged as the most common descriptors used. Their relationship to physiological stimuli and respiratory pathology provides a working framework for current research and clinical management. Combining these descriptions of breathlessness with quantitative measures such as questionnaires and rating scales has permitted the systematic study of the quality and intensity of these perceptions.

Assessment tools

For many years, there was no assessment tool for breathlessness of any aetiology, only disease-specific quality-of-life tools. This meant that palliative care clinicians, who see patients with any illness, had no accurate way of gauging the impact of their interventions or understanding the course of an individual’s symptom. Single-dimension rating scales, such as the Borg scale, VASs and NRSs, have been the quantitative tools responsible for forming the present construct of breathlessness (covered in another chapter of this Monograph [22]).

Recently, two additional instruments for the measurement of breathlessness in clinical practice (Dyspnoea-12) and in clinical research and laboratory settings (the MDP) have been validated, as described elsewhere [23, 24]. These developments represent a major advance in both enhancing communication between patients and clinicians and enabling the completion of good clinical and laboratory research. Both tools encapsulate Comroe’s construct of understanding the sensory and affective dimensions of the symptom.

Assessment and prognosis

The prognostic importance of breathlessness for longer-term survival has been known for some time [15]: now the availability of the MDP has enabled researchers to demonstrate that it is also related to short-term prognosis [25]. This increasing recognition that the severity of an individual’s breathlessness gives a better indication of their prognosis than other measurable variables, such as lung function [26–28], gives additional weight to Comroe’s interpretation of breathlessness as linked to outcome. Predictive tools are available for accurately establishing the short and longer term prognostic implications of the state of being breathless (covered in another chapter of this Monograph [29]). This will help clinicians to understand the importance of assessing breathlessness and patients to understand the importance of personally actively managing their disease [30]. It is clear that patients do not always understand that breathlessness is a serious long-term symptom until they are severely disabled. People with poorly managed breathlessness make extensive and often futile use of medical services; this may bring the symptom higher up the list of managerial priorities in a way that descriptions of individual suffering have not. All health systems are keen to reduce unscheduled use of services, particularly admissions to hospitals and attendances at EDs. The communication with a patient about breathlessness will be distinct from that with a colleague in another medical specialty, or with a scientist or a manager; the language needs to be chosen to give the message the best chance of being heard.

Some work in progress

Many different aspects of our understanding of breathlessness are still developing and are in need of further investigation. A few of these are discussed below.

Qualities of the experience

The present general agreement that there are three distinct qualities of breathlessness, “air hunger”, “work and effort” and “tightness”, is based on population studies of diverse groups using statistical clustering and factor analysis [31, 32]. These terms and their synonyms are selected by both healthy people and patients, with air hunger being the most prominent. Yet people in these groups also described their experience with a variety of other words and expressions, some of which may be unique to a culture or individual [33]. As many different sensory inputs are activated together in normal and pathological breathing, and their separate contributions are not well understood, the present classification is subject to extension and refinement. Individual patients, through experience, have become sensitive to many changes in their breathing that are not revealed in population studies, yet their verbal descriptions may be useful in their clinical management. We still cannot currently link descriptors of chronic breathlessness reliably to discrete pathologies [34, 35], although “chest tightness” is always linked to asthma. Future studies may find apparently idiosyncratic descriptions to be common to certain clinical conditions. The construct of breathlessness will be enriched by continued studies of the variety of verbal descriptions available to patients and carers.

Intensity of the experience

At one time, doctors did not recognise the range of possible individual responses and some talked (some still do) about “disproportionate breathlessness” [36], because it was not understood that a defined level of disease severity (commonly measured by pulmonary function tests) did not equate to a consistent level of breathlessness in different individuals. Breathlessness severity has been shown to correlate better with prognosis than lung function in those with COPD [15], the general population [26] and other disease groups [27]. In carefully selected individuals given lung volume reduction surgery, only 50% are significantly improved symptomatically, in spite of increases of lung function of 25% of more [37]. This suggests the need to study the contribution of many factors other than lung function to the intensity of the symptom, such as a patient’s general health (both psychological and physical) and their social support, health beliefs and cultural influences. Breathlessness may well correlate better with mortality because it represents the cumulative impact of a number of individual characteristics. The relative contribution of different qualities of breathlessness to its overall intensity, as measured on a single-dimension scale, is also in need of further study [31, 38].

Accessing the experience

Our evolving construct depends on the way an individual’s private experience is accessed and interpreted in their interaction with the investigator or clinician. What we tell them and what they tell us in our continuing dialogue is at the heart of all our efforts to understand and relieve their discomfort. The nature of this interaction in relation to patient compliance and treatment outcomes needs more study. Bridging the gap between the patient’s and clinician’s separate understanding of the symptom is especially important where communication is difficult, as in palliative care. There are a number of barriers to communication because of problems such as fatigue, cognitive deficits, somnolence, being on a ventilator or language difficulties. This may require the development of new ways for patients to rate and express their breathlessness, perhaps including picture scales [39], or hand or facial gestures, as well as a better understanding of the relationship of observed signs (e.g. respiratory, postural, facial) to breathlessness.

As important as the present validated measures are in providing uniformity and comparisons across studies, there may still be a need to extend them to groups or situations quite different from those used in the validation [31, 40]. The history of the most widely used measures of breathlessness and pain (e.g. Borg scale, McGill pain questionnaire) shows that they have been modified and supplemented to meet such needs.

Individual differences

The personal differences that can influence a person’s ratings or verbal reports of breathlessness are still poorly understood, such as differences in stoicism, sensitivity and somatisation (i.e. the expression of distress through bodily sensations and symptoms, common in those who have had traumatic early life experiences). There is evidence that individuals can vary widely in their interpretation and use of validated rating scales [41]. These variations might be revealed with the use of systematic debriefings and studies of the effect of instructions on the use of rating scales.

Situational differences

There is a need to continue to understand the relationship between laboratory studies of breathlessness and the “real life” experiences: in what ways are they similar or different [42]? The former allows the control necessary to separate and understand the various contributions to the experience but cannot duplicate the results of a patient’s altering their behaviour to reduce their discomfort. A good example of these difficulties is comparing the results of imaging studies with their necessary constraints to life situations [43–45]. Those in a laboratory know that the experience of breathlessness will end and that it has no relationship to an underlying disease, which may be life threatening. They do not experience the interaction of their family’s response to their breathlessness. In the laboratory situation, breathlessness is expected and the atmosphere is calm. Nonetheless, those who have experienced extreme “air hunger” under laboratory conditions have reported that they found the experience unbearable.

Opportunities for exploration

There are a number of areas in which we need a better understanding of breathlessness in its biological and psychophysiological context. Some of these are discussed below.

Role of systemic inflammation and ageing

Chronic, systemic inflammation is now linked to many disease and symptom states where it was not recognised previously, such as schizophrenia, depression, cardiovascular disease, COPD and cancer. The degree of inflammation measured as the level of a simple acute-phase protein (C-reactive protein) may be a reliable guide to prognosis in these illnesses [46], as well as in more obviously inflammatory illness such as the vasculitides.

It is sometimes uncertain whether chronic inflammation is a cause of ill-health or an effect [47]. It is well established that an individual’s emotional status can affect and be affected by chronic inflammation, and it is clear that inflammation worsens symptom severity in, for example, pain. This work has not yet been carried out in breathlessness or extensively in respiratory medicine, although its importance has been suggested [48, 49]. It is interesting to note that “accelerated ageing” from an imbalance of the inflammatory response (“imflammaging” [50]) or abnormal activation of the inflammatory response is now considered important in many apparently diverse areas of medicine, such as depression [46], schizophrenia [51] and cardiovascular disease [52], as well the ageing process itself [50], and in many symptoms, such as cachexia [53] and pain [54]. Age-related changes in a patient’s response to breathlessness are especially important in palliative care. Promoting healthy ageing as well as active disease management is now recognised to require a multidimensional approach, encompassing attention to diet, psychological approaches that enhance a sense of agency and resilience [55], and the promotion of physical and mental exercise.

Understanding the placebo effect

BENEDETTI and co-workers [56, 57] considered the study of the placebo effect to be contiguous with “studying the psychosocial context around the patient” at the time of the treatment, and that “it is a psychobiological phenomenon that can be attributable to different mechanisms, including expectation of clinical improvement and Pavlovian conditioning”.

As we understand that shortness of breath is generated in the central nervous system and influenced and conditioned by psychological, social and environmental factors, it becomes obvious that it is essential to understand and utilise the placebo effect when trying to maximise the impact of the few treatments that there are for breathlessness. It also makes it easier to understand why the “way treatments are delivered” is central to their effectiveness [58]. The ability of any of the current treatments to reduce breathlessness can probably be enhanced by understanding the principles that produce and enhance the placebo effect: these include the importance of social reinforcement, information about demonstrated effectiveness and positive feedback for any success [59].

This effect may be particularly important for non-pharmacological treatments. An example is use of a hand-held fan to relieve breathlessness. This is one of the central management strategies used by the Cambridge Breathlessness Intervention Service (BIS). This cheap, portable, safe, everyday piece of equipment has the potential to increase self-efficacy, encourage exercise and reduce anxiety by increasing the internal locus of control of breathless patients. Its very strengths may also be its weaknesses, as it is not a drug and does not look like a sophisticated piece of medical equipment. It can only be transformed into this if explanations of the most effective ways for it to be used are given by a convinced clinician. The evidence of its efficacy needs to be cited [60, 61] and a demonstration given: the art of medicine needs to be employed [62]. In a longitudinal study of patients with COPD who were not advised about the use of the fan, it added nothing to standard care [63].

The many likely mechanisms and the impact and effective use of the placebo effect need urgent investigation. It is clear from pain research that placebos may exert their analgesic effects through the same spinal pathways involved in pain relief by opioid therapy [64, 65]. These effects are likely to be at least as useful as the few drugs available for breathlessness palliation and much safer in those with chronic conditions, who may live for many years.

Evolutionary role of the perception of breathlessness

Most of our life-sustaining physiological systems continue automatically, without any indication of change reaching consciousness. Breathlessness is controlled both voluntarily and automatically. The needed behavioural responses require perceptual and cognitive processes that are dependent on cortical structures. Changes in breathlessness are also often linked to a feeling, such as fear, joy or anxiety. DAMASIO and CARVALHO [66] postulated that “the addition of a felt experiential component to sensory mapped body afferent signals emerged and prevailed in evolution because of the benefits it conferred on life regulation” and that “felt experiences permit more flexible and effective corrective measures than somatic mapping alone, especially in the realm of complex behaviour”. The authors suggested that an accompanying feeling could be of evolutionary advantage in that it gives a necessary motivational edge to experiences that require adaptive changes in behaviour to correct homeostatic imbalances. They postulated that it may be helpful to regard chronic breathlessness (and pain) as “pathologies of feeling” in trying to develop more effective treatment strategies. This interpretation of breathlessness lends support to the use of complex interventions in treatment [58, 67]. It is noticeable that patients in the Cambridge BIS evaluation stated that “the way the intervention was delivered”, and thus the feelings evoked by the treatment strategies, was important in its success [58].

Neuroscience research is delineating in more detail the contributions of different areas of the brain to the sensation of breathlessness. Recent work has demonstrated that separate parts of the periaqueductal grey matter may be responsible for different aspects of the complex feeling, with one area subserving the intensity of the sensation and one anticipating it [68]. Progress in our understanding of the biological-evolutionary role of breathlessness will require research strategies relating human brain studies of the possible substrates of breathlessness with animal studies of similar neural systems. Of great advantage would be the development of animal models similar to those used successfully in studying pain. This is discussed further in another chapter in this Monograph [69]. Behavioural techniques using operant or conditioned learning techniques still need to be developed, perhaps in collaboration with workers in veterinary science for whom animal breathlessness is a major concern [70, 71]. Such behavioural techniques may also be applicable in assessing and control of breathlessness in noncommunicative patients.

Breathing practice as a way to better general physical and psychological health

There has been a recent rediscovery in the west of ancient Eastern traditions of breathing training, martial arts and yoga movement, and interest in their possible relationship to improved health [72, 73]. Research into mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive therapy is growing rapidly, and some evidence strongly suggests that it can have an equal impact to standard drug therapy regimens in preventing relapse in severe depression [74] and that it may be beneficial in other conditions in helping to improve the quality of life. There is also evidence to suggest that “yoga breathing” can have beneficial effects on oxygen saturation and general health in those with severe heart failure [75, 76]. There is very little discussion, and much less research, on any potential for these ideas to help severe breathlessness in advanced disease, and any construct of breathlessness needs to encompass future evidence and understanding in these areas.

Our construct in action: patient-centred symptom management

A scientific analysis of the construct of breathlessness is a sterile academic exercise if divorced from the human need from which it arose. The two essential questions of “What do we know about it?” and “What do we do about it?” cannot be separated. Our understanding of the many aspects of breathlessness should guide our management of the symptom, but our success in this depends largely on the active participation of the patient.

As in all good medical practice, an interactive rather than a didactic clinician-to-patient approach will help us make patients collaborators in their care, rather than passive recipients. To some extent, this ideal “standard of practice” is followed in many facilities and institutions. There may still be a need for formal training and investigation of this collaborative process because it is so important in long-term care of chronic breathlessness. The following are just three examples of directions this might take.

Understanding and changing a patient’s “personal construct” of breathlessness

According to the psychotherapeutic theory of “personal construct”, developed by George Kelly [77, 78], a person’s mental construct is the lens through which they see the world: understanding it, explaining events and making predictions about it. These can be changed or corrected by further experiences and by getting new information. The individual is seen as continually testing, modifying and enlarging this view. Although clinicians may use our current conception of breathlessness to help the patient cope with the symptom, the patient comes with his or her own “personal construct” of breathlessness. This is based on what they have learned during their life and from many other sources during the course of their treatment (which may have lasted years), as well as being derived from their experiences with their disease. This forms the basis for their way of living and coping with breathlessness, but may also consist of misinformation and making intuitive but counterproductive responses, or responding to conflicting advice from different clinicians. The ability of people to revise and enlarge their personal construct makes it likely that clinicians and caretakers can reshape the patient’s understanding of their symptom, thereby helping them participate more effectively in its management. Clinicians’ personal constructs of breathlessness need to be similarly informed.

The translation of the formal elements of our scientific construct into a form that is helpful to a patient is an important part of this process. Thought must be given to creating scripts that can be used, tested and revised, such as the following:

Chronic breathlessness, the shortness of breath you feel when you have an illness that cannot be cured, is very different from the sensation you feel when you are healthy and run up a hill, or swim, or do something athletic or joyful. This shortness of breath has no happy associations; it is often frightening, upsetting and very disabling. It is also stressful for those closest to us: they want to help but don’t know how to. It is usual to feel anxious, even panicky, when you feel breathless. Often those closest to you will feel helpless, and sometimes frightened, when you are having a bad attack of breathlessness.

We feel frightened because our bodies are programmed, like a machine, to need to breathe. This drive to breathe is very strong for all of us, and not being able to breathe properly is associated with very serious anxiety, caused by our brains trying to put things right. Being short of breath is so horrible that often we try to avoid it by resting; this makes our muscles weak and we become unfit. We will get more and more breathless if we simply rest all the time, trying to avoid being short of breath.

We know now, from medical research, that we need to use both our muscles and our minds to improve our own shortness of breath when we are ill. We need to change our behaviour and react differently to being breathless. We can alter the way we feel about breathlessness, making it less frightening and restricting. Changes in the way we feel can be as powerful as a drug in helping our illness improve. We often need help from other people to change our reactions to being breathless and to start to feel less frightened by it.

This may be the beginnings of a construct for patients, families and lay people affected by breathlessness or trying to help someone who is. These are therapeutic tools that, to the best of our knowledge, have not been studied or exploited in the management of breathlessness.

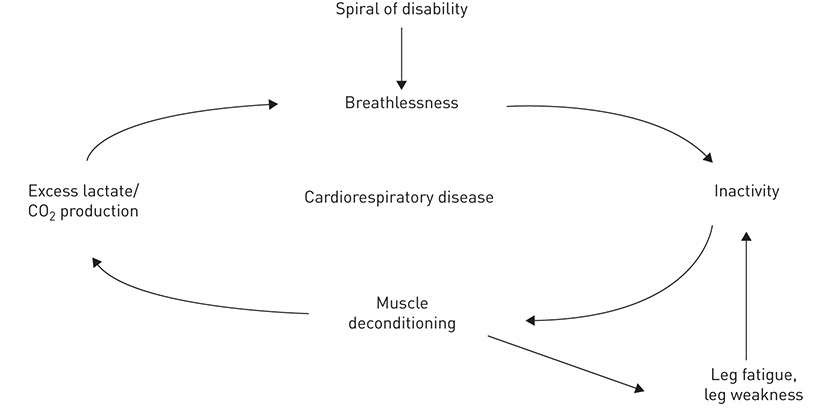

Understanding and interrupting the spiral of disability

The benefits for health of exercise and a nonsedentary lifestyle are becoming irrefutable, with evidence from all areas of medicine, even in those with advanced disease [79]. Breathlessness research is rich in studies that demonstrate that “deconditioned muscles” have a different structure to those that are exercised regularly, leading to the earlier onset of lactic acidosis and leg fatigue on walking. This “breathlessness→rest→deconditioning→more breathless at lower levels of exertion” has been called the “spiral of disability” (figure 1).