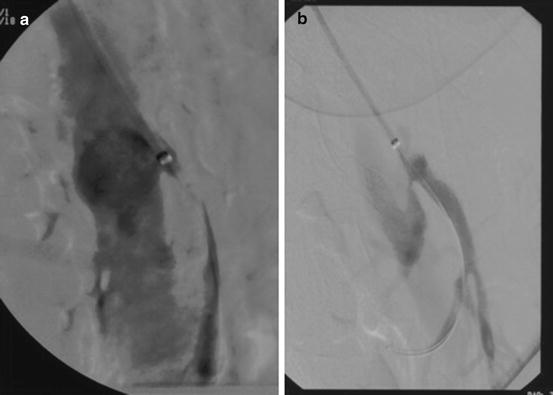

Fig. 18.1

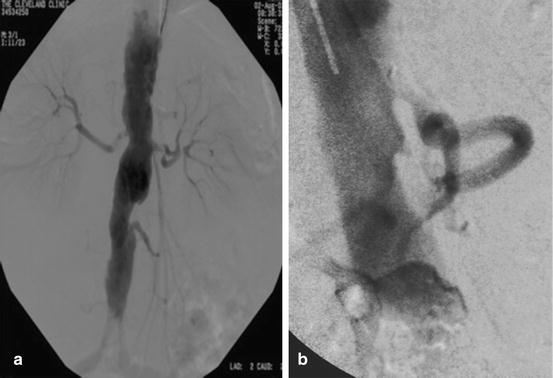

(a) CT scan and (b) diagnostic angiogram of acute SMA occlusion

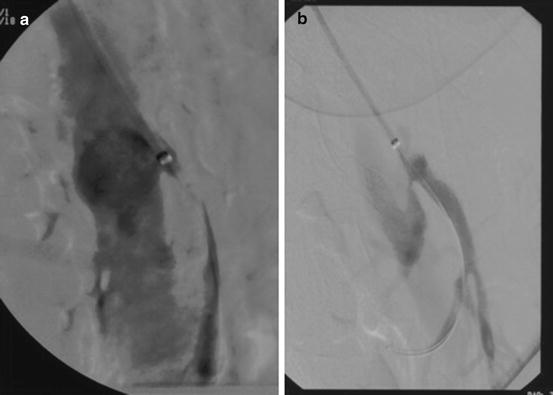

Fig. 18.2

(a and b) AP and lateral angiogram depicting visceral vessels

Fig. 18.3

Meandering mesenteric artery

If the patient has complete occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery and their clinical condition will allow, we will attempt thrombolysis. Some contraindications to thrombolysis include severe hypertension, gastrointestinal bleeding, and embolism from atrial fibrillation. There are specific technical considerations to consider. The first step involves recanalizing and/or crossing the lesion. We usually use left brachial access as our initial approach as the angle makes it much easier to cross the lesion antegrade (Fig. 18.4). A long 5 F sheath (70–90 cm) usually is sufficient to provide adequate stability for tracking, as the final intervention will need to move to a 0.014 in wire. We usually use an MPA catheter and bury it into the stub of the occluded vessel, as it easily adapts to the curve of the aorta. Next I “drill” a 0.035 in stiff glide wire through the lesion, and then if possible pass the MPA catheter or a quick cross catheter through the lesion (Fig. 18.5). Once we have crossed the lesion, it is imperative to get an angiogram to confirm you are in the true lumen. If you have not reentered the true lumen, the catheter will need to be withdrawn and a new attempt should be made. If there is thrombus distal to the orifice and we have reentered and are not in a dissection plane, we will attempt thrombolysis with a short tip infusion catheter and/or wire [10]. The patient is then bolused with 2 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), and an infusion is started at 1 mg/h. We also keep the patient on a slightly higher dose of heparin that lower extremity ischemia, maintaining the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) near 40 s. If the patient’s fibrinogen drops below 150 mg/dl, we then decrease the infusion rate to 0.5 mg/h. If the fibrinogen drops to 100 mg/dl, then we will either give cryoprecipitate or suspend the infusion depending on the patient’s clinical condition. If the patient demonstrates any signs of increasing abdominal discomfort, rising lactic acidosis, or clinical deterioration, we then stop and prepare for open surgery. Repeat angiograph is performed every 12 h. Once the distal clot clears, we then proceed to definitive angioplasty and stenting. If there is spasm, we will use either 30–60 mg of papaverine or 200–400 μg of nitroglycerine. If the clot has not cleared within 36–48 h, we will attempt mechanical thrombectomy with the Possis mechanical thrombectomy catheter [11]. A 0.014 in wire is needed for 5 F and 0.035 in wire for 6 F. Additionally, I prefer to use an embolic protection filter to prevent embolization, as this has been reported as high as 19 % for peripheral pharmacomechanical thrombolysis [12].

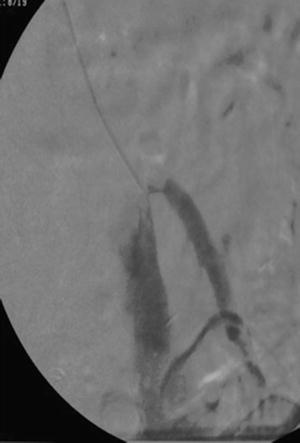

Fig. 18.4

MPA catheter with antegrade approach to the SMA

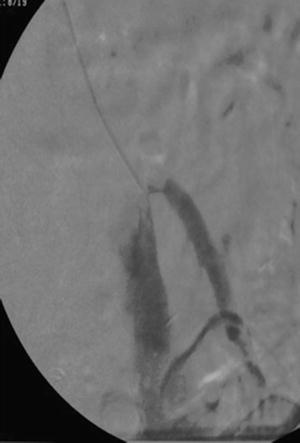

Fig. 18.5

Sheath and wire across occluded SMA

The typical culprit lesion from in situ thrombosis usually occurs from extension of an orifice lesion. However, it is not uncommon for lesions of the superior mesenteric artery to extend further. If there is not distal thrombus, immediate revascularization with balloon angioplasty and stenting is warranted. For orifice lesions of the celiac, SMA, and IMA, we use a balloon expandable stent (Fig. 18.6), and for more distal lesions we will use a self-expanding stent to adapt to curves (Fig. 18.7). Occasionally, we will have to use a combination of a self-expanding stent distally and of a balloon expandable stent proximally. Recent data from the Mayo Clinic [13] now supports the use of an ePTFE-covered stent graft for chronic mesenteric ischemia, and we have extended this to AMI for thrombosis in situ. For patients with AMI from embolism, we will attempt percutaneous mechanical thrombolysis with the Possis thrombectomy catheter. If their clinical condition will allow it, we will get a transesophageal echocardiogram, and if there is no clot in the atrium, we will also offer them thrombolysis. If this is unsuccessful or there is suspected persistent atrial thrombus, we will either attempt stenting with a covered stent or proceed with open embolectomy.

Fig. 18.6

Balloon expandable stent in orifice of the SMA

Fig. 18.7

(a) Selective SMA angiogram with disease beyond the orifice. (b) Self-expanding stent adapting to the curve

In circumstances where the patient’s condition warrants emergent or urgent laparotomy, recent efforts have focused on a hybrid open surgery/stenting procedure [14, 15]. The technical details of this consist of performing the procedure in a hybrid operating suite and immediate exploration for control of sepsis and enteric spillage. We have been more inclined to use the brachial approach rather than the direct SMA cutdown if possible, as it allows more rapid revascularization. Nevertheless, there are advantages of the direct SMA cutdown as it will allow embolectomy. The procedure begins with dissecting the SMA out at the inferior margin of the pancreas or base of the transverse mesocolon. The artery is cannulated with a micropuncture needle, wire, and catheter, and then retrograde angiogram is performed. A 0.035 in wire is then used to exchange out for a 5 F sheath, and diagnostic imaging is performed. The lesion is crossed and the wire and a longer sheath are advanced into the aorta. Balloon angioplasty is frequently necessary before passing the sheath, and this usually requires exchanging out to a 0.014 in system. Retrograde stenting is done in the same fashion as antegrade which was previously described. It is not uncommon to have to perform a concomitant embolectomy, which can also be done with an over-the-wire balloon embolectomy catheter. On completion, the vessel is closed with either a vein or bovine pericardial patch angioplasty.

Less common etiologies of acute mesenteric ischemia include thoracoabdominal aortic dissection (TAAD), mesenteric venous thrombosis, and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Acute mesenteric ischemia occurs in between 15 and 42 % of patients who suffer from TAAD [16]. Patient’s symptoms include not only those severe of mid-thoracic back and chest pain but also abdominal pain. The diagnosis of AMI is entertained based on symptoms but also CT scan evidence of obstruction of the visceral vessels from the dissection flap (Fig. 18.8). Additionally, it is not uncommon in these circumstances for multiple visceral branch vessels to be involved. Symptoms can also be classified as subacute with waxing and waning of symptoms due to dynamic movement of the dissection flap. The morbidity and mortality with open surgical therapy have been previously described and remain as high as 50 % [16]. In 1999, Dake first described treatment for TAAD with a thoracic aortic stent graft [17]. Since that time there have been numerous studies documenting the success of endovascular therapy in treating malperfusion from TAAD [18–20]. Treatment in these circumstances consists of expansion of the true lumen with a thoracic stent graft, and occasionally an adjunctive self-expanding stent will need to be placed in the individual branch vessel. There are a number of technical details necessary to accomplish this, starting with preparation for bilateral femoral artery access, and be prepared to do an iliac conduit. Additionally, it is essential to have left brachial artery access, so the arterial line for blood pressure monitoring should be placed on the patient’s right side. Intravascular ultrasound is a necessary adjunct. We usually perform a right femoral artery cutdown and obtain left brachial artery access from the start. The first step is to confirm you are in the true lumen, and here intravascular ultrasound is essential (Fig. 18.8). We then obtain an arch aortogram (Fig. 18.9) and exchange out for a 0.035 in stiff Lunderquist wire. A pigtail catheter is then placed from the left brachial artery into the aortic arch, which not only takes angiograms but also marks the subclavian artery. Often in an emergent setting, it is necessary to cover the origin of the left subclavian artery to cover the entry tear. A subsequent emergent carotid subclavian bypass is necessary if there is not a normal size contralateral vertebral artery or if the patient is known to have an incomplete circle of Willis. Once the stent graft is placed, a distal angiogram is taken to confirm expansion of the aortic true lumen and evaluate the patency and flow of the visceral vessels. Occasionally, the dissection flap will necessitate the need to place a self-expanding stent into the branch vessel if flow remains compromised (Fig. 18.10).